Too Grateful To Complain?

Why organ transplantation lags behind oncology in innovation and public voice

This guest post is part of an ongoing series that spotlights voices across kidney care. This week’s post is by Karin Hehenberger, MD, PhD, President at Lyfebulb, Chief Medical Officer at Patient Care America, and an expert in the fields of transplantation, metabolic disease and autoimmunity.

Organ transplantation is one of medicine’s greatest triumphs. It transforms imminent death into renewed life, often overnight. But behind this miracle lies a troubling truth: the field has barely advanced in decades. While oncology races ahead with precision therapies, immunotherapies, and fast-track drug approvals, transplant medicine remains stuck. Thus the field lags far behind in innovation, regulatory speed, investment, and public attention.

Why? In large parts because transplant patients are too grateful to complain, and too often, their doctors dismiss the need for change.

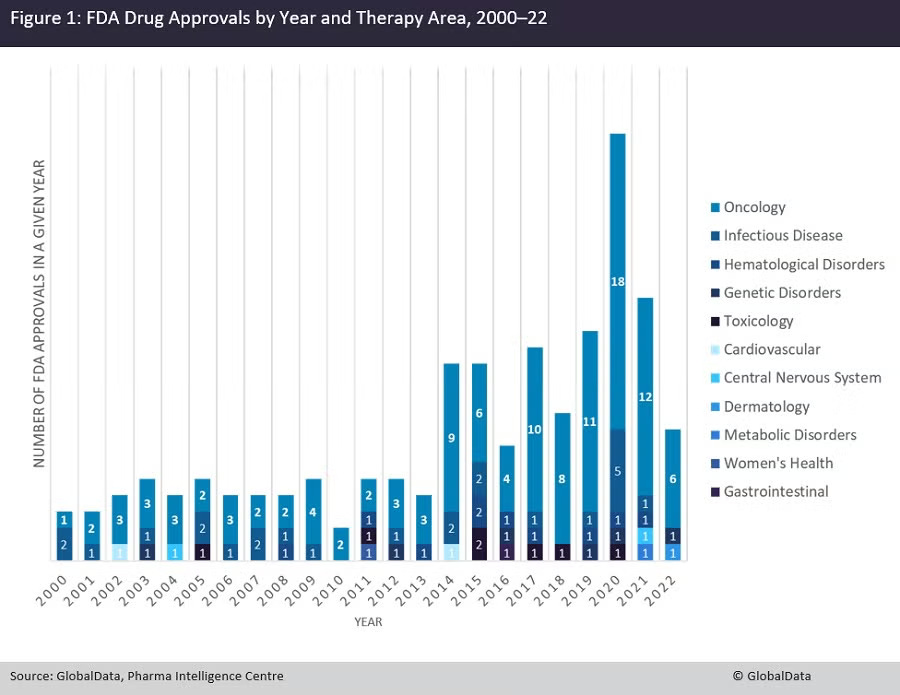

Cancer patients transformed oncology not just with science but with their voices. They demanded staging systems, quality-of-life measures, and personalized care. Regulators listened: nearly 70% of the FDA’s accelerated approvals since the 1990s have gone to cancer drugs.1 Investors piled in. Today, oncology dominates biotech.

Transplantation tells the opposite story. Graft health is measured in crude, binary terms: working or failing. Patient-reported outcomes almost never decide drug approvals. Biomarkers exist but are used sparingly. And the pipeline for new transplant drugs? It is there but limited and very few large pharmaceutical companies note transplantation as a core area of interest.

Why does transplantation, a field where lives depend on fragile graft survival, not command the same urgency as cancer? One explanation lies in the patient voice, or the lack of it.

Gratitude as a Double-Edged Sword

Cancer patients have long demanded more. Their advocacy reshaped research, regulation, and investment. Oncology now boasts staging systems that tailor treatments by severity and type, precision diagnostics that enable targeted therapies, and clinical trials that measure not just survival but quality of life.2 Regulators responded: oncology accounts for the majority of FDA accelerated approvals.3

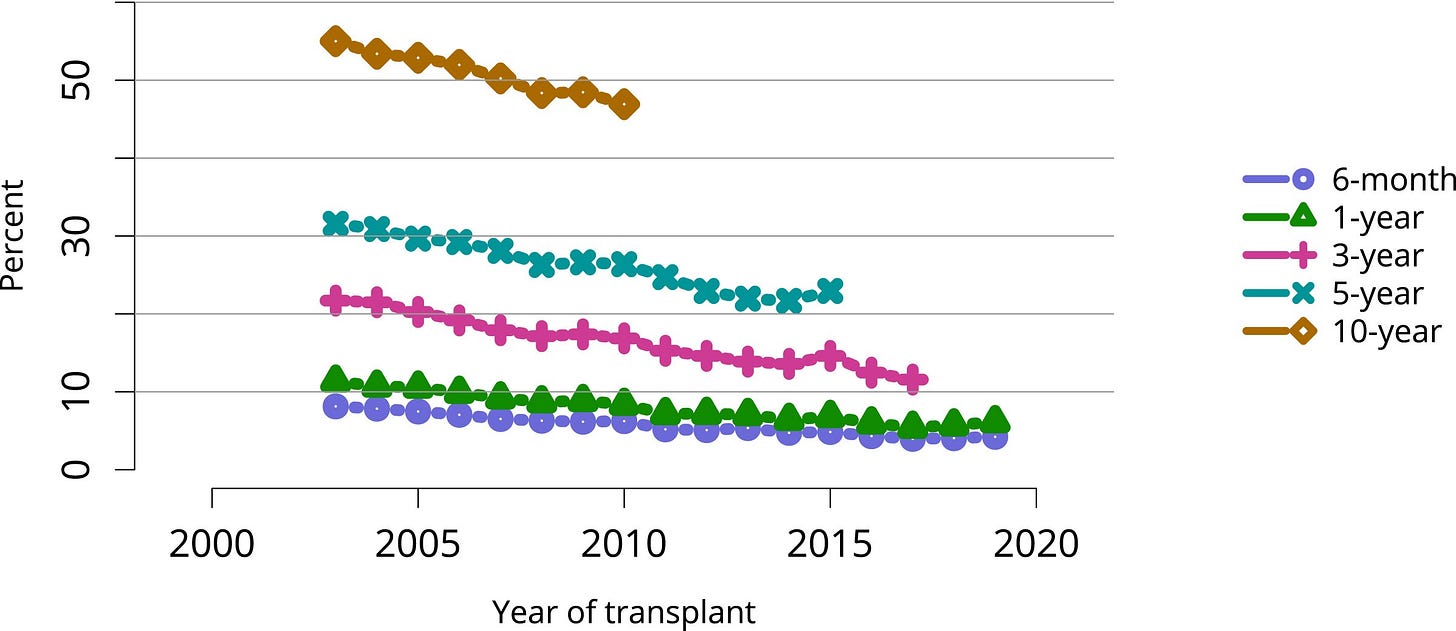

Transplantation remains muted. Too often, success is reduced to a single metric: one-year graft survival. Nearly every center clears that bar, but the longer view tells another story. By five years, graft survival falls to 85–90%, and by ten years, deceased-donor kidneys function in only 50–65% of recipients.4

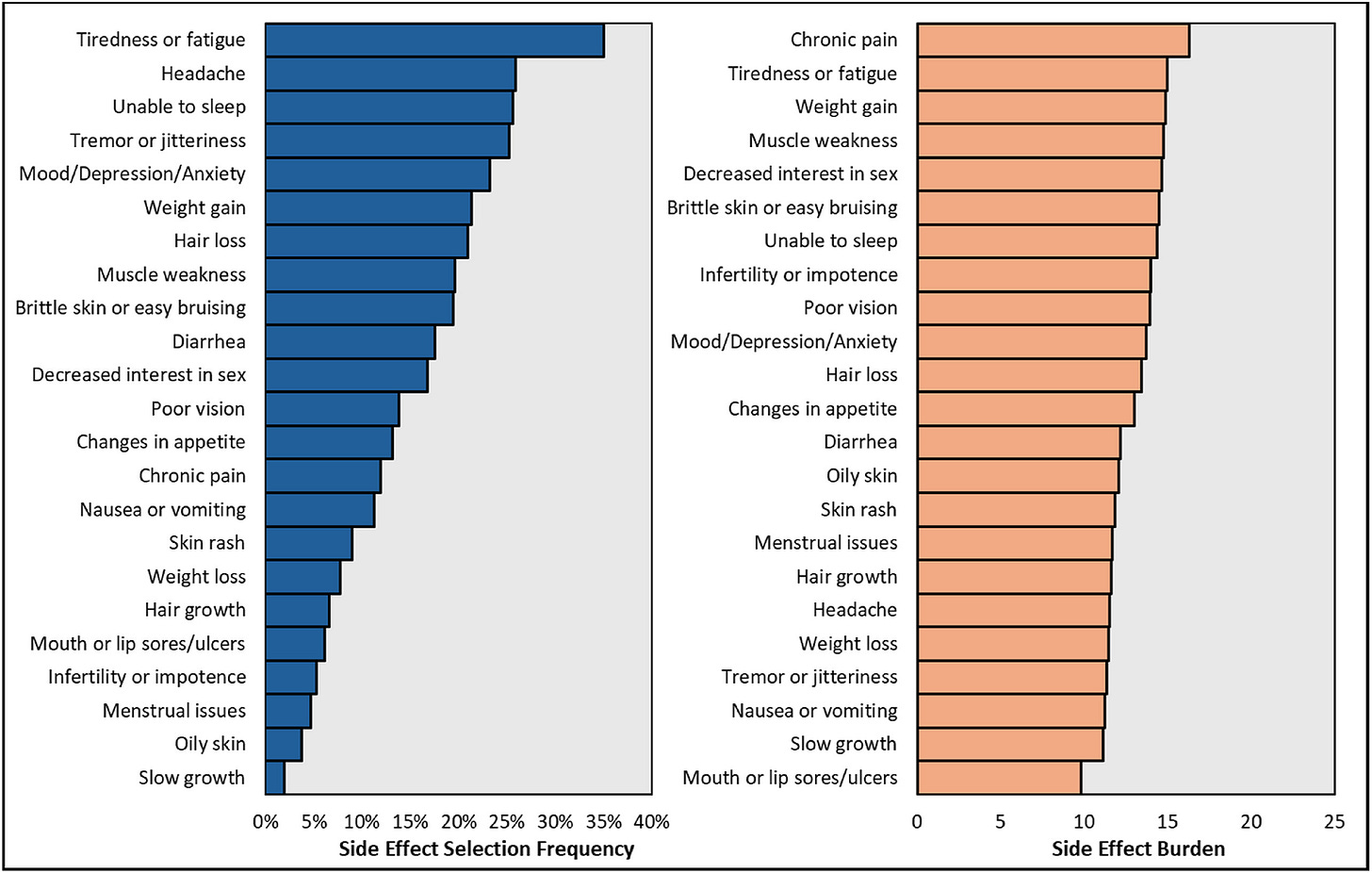

And patients live with daily trade-offs: toxic drugs that preserve organs but fuel infections, cancers, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.5 Quality of life is also an issue in transplant recipients, with severe side effects, due to immune suppressants, like tremors, brain fog, hair loss, diarrhea, and mouth sores are part of daily life for the remainder of the graft survival.6

Figure: Reported Side Effects in Transplant Recipients

Cancer drug approvals study reduction of tumor mass which is a measure of quality of life as well as long term prognosis; there were 13 new approvals in 2023 alone. If transplantation were judged by the same standards, long-term graft survival and quality of life, its shortcomings would be impossible to ignore.

Why the Silence?

I know because I lived it. At 16, I was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes. Twenty years later, my kidneys and eyes were failing. My father gave me one of his kidneys. 9 months later, I received a pancreas from a young woman who had died too soon, freeing me from the relentless cycle of blood sugar swings and insulin injections.

But the very drugs (immune suppressants) that protected my new organs damaged them too. They left me vulnerable to infections, malignancies, and complications that mounted until my kidney failed again. I survived thanks to my sister, who donated one of hers.

This is transplantation’s cruel paradox: the very medicines that extend our lives also shorten them. They preserve grafts but erode quality of life. They keep us alive but at a price too high to call “good enough.”

And yet transplantation allowed me to have my biological daughter. For that I am endlessly grateful and endlessly determined.

I am not alone. All 250,000 or so American transplant patients live with the heavy toll of the drugs we must use daily. Long-term immunosuppression leaves recipients up to 100 times more likely to develop skin cancer. Serious infections strike as many as half of recipients in the first year. A third develops diabetes, linked to their medications. Others cope with kidney toxicity, osteoporosis, high blood pressure, tremors, brain fog, weight gain, or hair loss. Quality of life often suffers dramatically, but you wouldn’t know it from the way trials are designed.

Still, patients hesitate to speak. “I don’t care if I take twenty pills a day,” one told me. “I was given another chance, and I can’t complain.” Another admitted, “The drugs make me sick, but without them, I wouldn’t be here. I’ll take whatever I’m told.”

Doctors can be just as resigned. “The drugs we have work well enough,” one transplant physician shrugged. Another said, “Patients tolerate them. We don’t need a new transplant drug every five years the way oncology does.” Gratitude on one side, dismissal on the other, and innovation stalls.

Innovation Requires Collaboration

Every transplant recipient walks this line between gratitude and frustration. To change the future, innovation must move faster. That requires academia, government, philanthropy, and industry working in concert, exactly like oncology did.

Progress depends on clinical pathways being more uniform and documented across centers to evaluate outcomes, research data being shared to achieve statistical significance, regulatory pathways allowing for composite markers and endpoints that incorporate long term outcomes and patient data. This in turn will drive interest from scientists and industry, and finance will follow.

Federal funding to support early science.

Venture capital willing to take risks.

Philanthropy to fuel novel approaches.

Public–private partnerships to share cost and risk.

The blueprint exists. Oncology proved it works. And even more importantly, science has reached a moment in time when there is finally hope again. Xenotransplantation stands at the threshold of transforming transplantation medicine. With more than 90,000 people in the United States alone waiting for a kidney, and thousands dying each year while tethered to dialysis chairs, the demand for organs far exceeds the available supply. Advances in genetically engineered pig organs and novel therapeutics with less toxicity suggest that xenotransplantation and new drug approaches could finally close this supply–demand gap. If successful, it would not only relieve the relentless burden of dialysis, but also shift the entire transplantation market from scarcity to scalability, redefining both patient survival and healthcare economics.

Breaking the Silence

For too long, transplant patients have been quiet. Gratitude for the gift of life stifles demands for better therapies. But gratitude and advocacy are not opposites. The best way to honor our donors—the family members, friends, and living or deceased strangers who give us a second chance—is to demand treatments that make their gifts last longer and safer.

Transplant patients are not failures. We are survivors. And we must tell our stories until the system changes.

What Patients Can Do

Patients themselves can accelerate change. We must:

Raise our voices to demand therapies that prioritize quality of life as well as graft survival.

Organize communities that provide peer support and collective advocacy.

Educate by sharing lived experiences with policymakers, researchers, and clinicians.

Drive innovation through entrepreneurship and partnership.

History shows the power of advocacy in cancer and HIV, big data in diabetes management, and peer-support in weight loss and substance use disorders. Finally patient entrepreneurs have created new approaches, including when Dr. Marie Krogh, herself living with diabetes, co-founded Novo Nordisk, today a global leader in metabolic disease.

Patients are not just participants in care. We can be architects of its future.

The Call

People die each day waiting for organs that never come. Those who receive them too often lose them too soon. To truly honor our donors, we must extend the lives of their gifts and improve the lives of their recipients.

The call is simple but urgent:

Honor the gift. Amplify the patient voice. Accelerate innovation—together.

Discussion

We hope you enjoyed this week’s post and topic. What are your thoughts? Share your comments, experiences, and questions with us in the comments below.

Potential: Where do you see the greatest untapped potential for improving transplantation? Is it in new drugs, better trial designs, patient-reported outcomes, or something else entirely?

Examples: Have you seen advocacy efforts, policy changes, or research collaborations that give you hope for faster progress in transplantation? Share examples of where patient voice or innovation has started to move the needle.

Advice: What guidance would you give to patients, caregivers, or clinicians who want to raise their voices and push for better therapies? What keeps you engaged in this work?

My thanks to Karin for sharing her voice and expertise with us. We first met through her work at Lyfebulb when I had the chance to participate in a patient-entrepreneur challenge. Since then, I’ve admired her journey and all she’s done and built to support patients. Connect with Karin on LinkedIn or by email at karin@lyfebulb.com. If you’re interested in learning more about these topics, you might enjoy recent Signals pieces on topics including life on immunosuppression, the iBox score, and Michelle Yeboah’s transplant journey. Thank you for being here with us.

— Tim

Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR, Winchester DP. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017 Mar;67(2):93-99. doi: 10.3322/caac.21388. Epub 2017 Jan 17. PMID: 28094848.

Dienstmann R, Vermeulen L, Guinney J, Kopetz S, Tejpar S, Tabernero J. Consensus molecular subtypes and the evolution of precision medicine in colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017 Feb;17(2):79-92. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.126. Epub 2017 Jan 4. Erratum in: Nat Rev Cancer. 2017 Mar 23;17(4):268. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.24. PMID: 28050011.

Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, Scher HI, Hudis CA, Sabbatini P, Rogak L, Bennett AV, Dueck AC, Atkinson TM, Chou JF, Dulko D, Sit L, Barz A, Novotny P, Fruscione M, Sloan JA, Schrag D. Symptom Monitoring With Patient-Reported Outcomes During Routine Cancer Treatment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016 Feb 20;34(6):557-65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0830. Epub 2015 Dec 7.

United States Renal Data System. 2022 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD, 2022.

Halloran PF. Immunosuppressive drugs for kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2004 Dec 23;351(26):2715-29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra033540. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2005 Mar 10;352(10):1056. PMID: 15616206.

Lim WH, Wong G, Pilmore HL, McDonald SP, Chadban SJ. Long-term outcomes of kidney transplantation in people with type 2 diabetes: a population cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Jan;5(1):26-33. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30317-5. PMID: 28010785.

Taber DJ, Gordon EJ, Myaskovsky L, Jesse MT, Peipert JD, George R, Chisholm-Burns M, Fitzsimmons WE, Gill JS. Therapeutic needs in solid organ transplant recipients: The American Society of Transplantation patient survey. Am J Transplant. 2025 Jul 29:S1600-6135(25)02860-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajt.2025.07.2474. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40744428.

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IXc-!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9f7142a0-6602-495d-ab65-0e4c98cc67d4_450x450.png)

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lBsj!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_48,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0e0f61bc-e3f5-4f03-9c6e-5ca5da1fa095_1848x352.png)