When delay becomes damage

A rheumatologist’s perspective on lupus, kidneys, and lost time

This guest essay is part of our ongoing series highlighting voices from across kidney care. Today we’re sharing a piece by Iqra Aftab, a practicing rheumatologist in South Jersey who cares for patients with lupus and other autoimmune diseases.

By Iqra Aftab

She was 21 years old. A young Black woman with unexplained fatigue, migratory joint pain, and a rash no one could name.

She was my first lupus patient, and she taught me a visceral lesson: In kidney disease, delay is not neutral. Delay is damage.

The silent stakes of lupus nephritis1

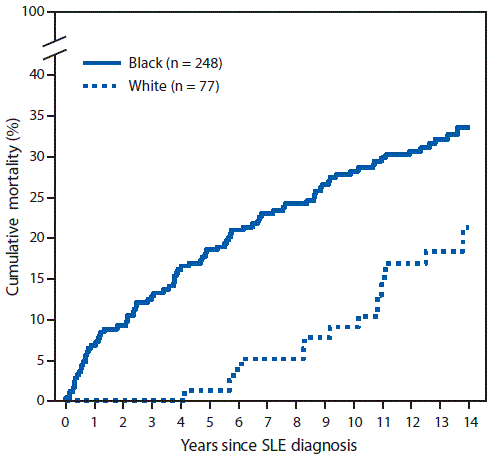

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) disproportionately affects young women of color. Black women are diagnosed two to three times more often than white women, develop the disease at a younger age, and experience more severe manifestations, including higher mortality at young ages.2 Among the most consequential manifestations is lupus nephritis, an immune-mediated kidney inflammation that occurs in approximately 40–60% of lupus patients, often within the first few years of diagnosis.3

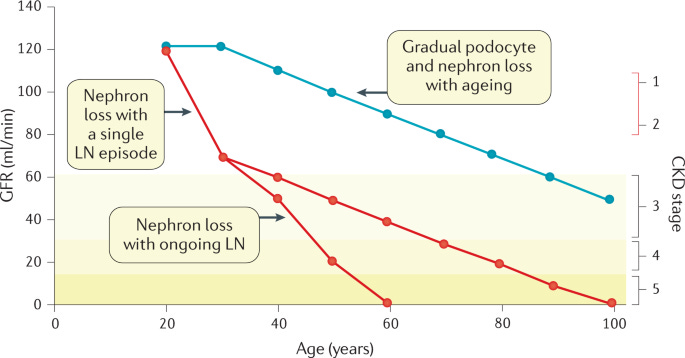

What makes lupus nephritis uniquely unforgiving is that the kidneys rarely announce their distress loudly. Proteinuria may smolder for months, and serum creatinine can remain deceptively normal. By the time laboratory abnormalities appear alarming, irreversible scarring may already be established. In lupus nephritis, treatment decisions are made not by symptoms alone, but by what the kidney tissue itself shows.

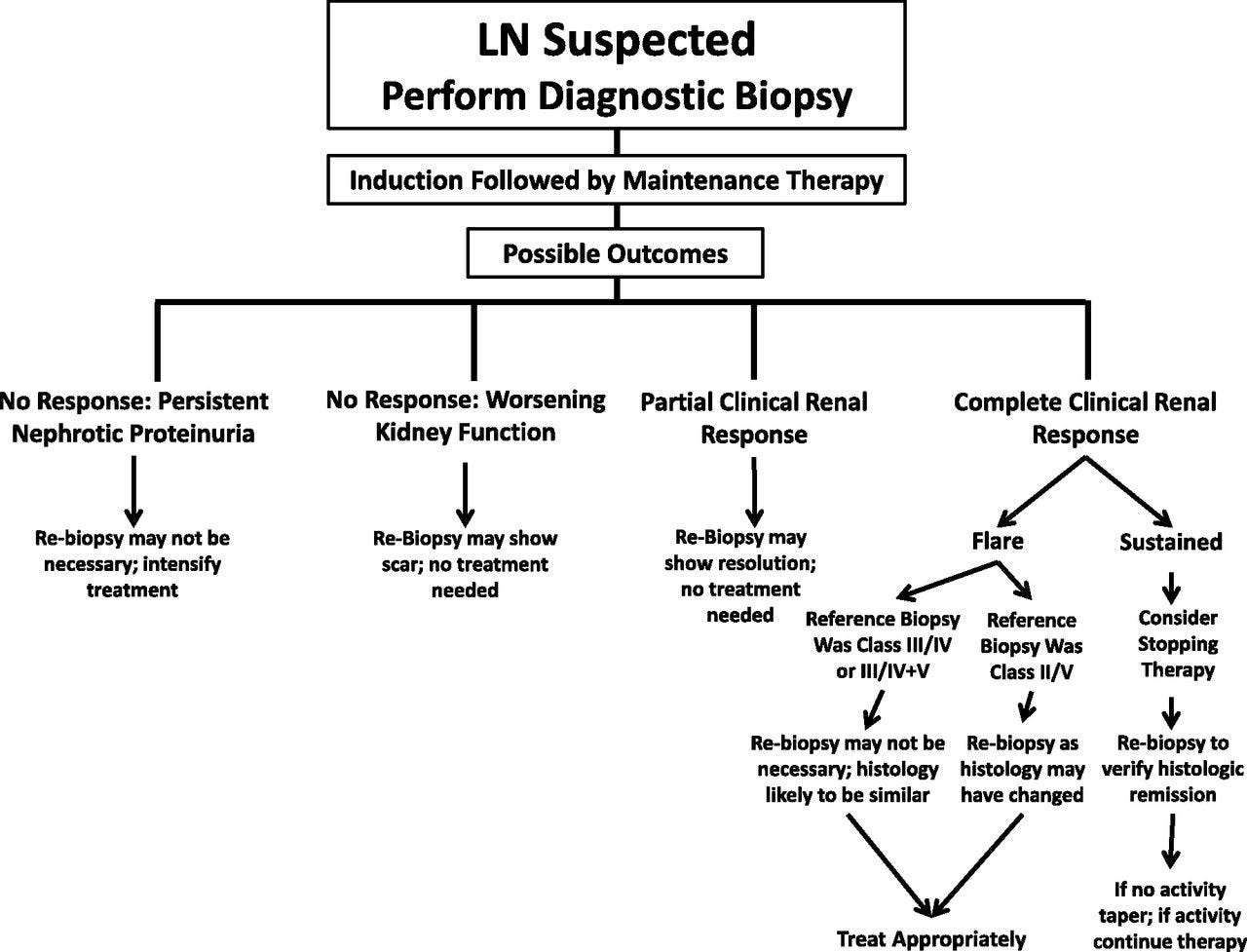

The only reliable way to distinguish reversible inflammatory injury from permanent chronic damage is a kidney biopsy. In lupus nephritis, biopsy findings determine disease class, prognosis, and treatment intensity. The biopsy is therefore not merely confirmatory, it is decisional. It tells us whether we are treating active inflammation or managing the consequences of injury already sustained.

For my patient, getting that biopsy became an uphill battle.

Three delays

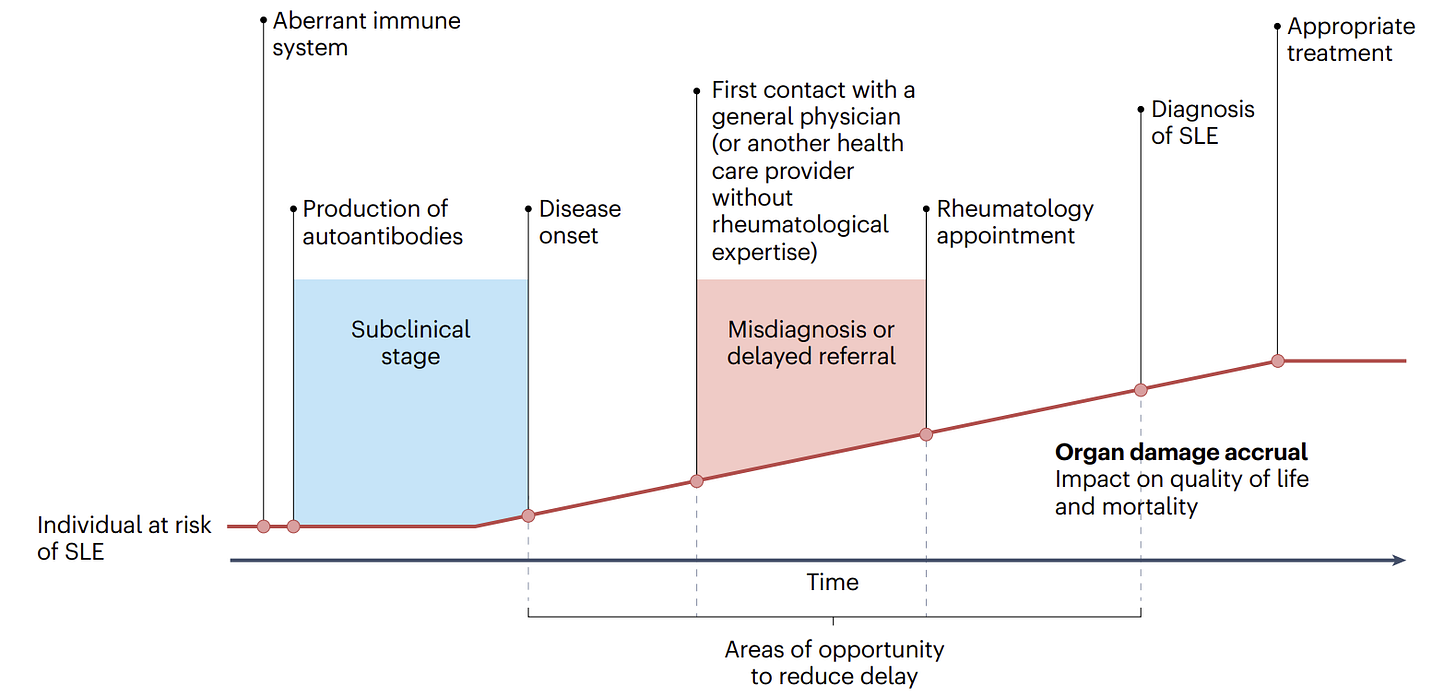

The first delay was diagnosis itself. Her symptoms: fatigue, joint pain, intermittent swelling, were diffuse and easy to dismiss. Like many young women of color with lupus, she did not fit a pattern that triggered immediate recognition, let alone urgency or timely escalation. Studies show that Black and Hispanic patients experience longer delays from symptom onset to lupus diagnosis and longer delays to subspecialty rheumatology care compared with white patients.4

By the time I met her, lupus had been active for months.

The second delay was the biopsy. I practice in South Jersey, a region that appears suburban on a map but functions like rural America when it comes to specialty access. Nephrology referral took weeks. Once nephrology agreed a biopsy was indicated, coordination with interventional radiology took additional weeks. Insurance authorization. Scheduling. Pre-procedure clearance. Each step was reasonable in isolation. Together, they created a delay the disease did not respect.

From the system’s perspective, this was a non-emergent procedure. From the patient’s perspective, it was not.

The third delay came with treatment escalation. When the biopsy was finally performed, it showed active inflammatory disease layered on chronic damage. The window for optimal intervention had narrowed. We initiated aggressive immunosuppression, but her proteinuria proved difficult to control. Second-line therapy. Third-line therapy. Prior authorizations. Toxicity monitoring. Each escalation introduced additional friction. Each step introduced delay not because options were unavailable, but because access to them was gated.

From the outside, it looked like her disease wasn’t responding to treatment. In reality, it was responding to treatment that came too late.

Delay is not distributed equally

This story is not an outlier. It is a pattern, and it falls hardest on those with the least margin for delay. These outcomes are not surprising; they are the predictable result of unequal access layered onto a time-sensitive disease.

Black patients with lupus are up to four times more likely to develop lupus nephritis than white patients and are more likely to present with high-risk histologic features on kidney biopsy.5 They experience faster progression to end-stage renal disease and lower rates of remission on standard therapies.6 Hispanic and Asian patients face similarly elevated risks of severe renal involvement and poorer outcomes.7

These disparities are not fully explained by genetics or baseline disease severity. They emerge where time-sensitive care meets fragmented access. Access plays a major role. In rural and underserved areas, nephrology care is limited; up to 40% of patients with advanced kidney disease meet a nephrologist for the first time within four months of initiating dialysis.8 In lupus nephritis, where biopsy findings directly determine treatment intensity, delayed access to nephrology and biopsy translates directly into delayed appropriate therapy.

Time-to-biopsy is not a scheduling metric. It is a prognostic one. Delays do not just slow care, they change the outcome.

What this means for kidney care stakeholders

For clinicians, this means recognition is the first intervention, not just screening. Lupus nephritis rarely presents dramatically. Mild proteinuria, intermittent hematuria, or subtle serologic changes may precede severe Class III or IV disease. Waiting for creatinine to rise is waiting too long. High-risk patients, particularly young women of color with lupus, require routine urine surveillance, early nephrology involvement, and a low threshold for biopsy. In kidney disease, vigilance is not defensive medicine; it is disease-modifying care.

For biotech, pharma, and diagnostics, this means drug efficacy is capped by timing. No immunosuppressive therapy can reverse kidney fibrosis that accumulates while patients wait for diagnosis or biopsy. When effective therapies appear to underperform, the problem is often not the molecule, but late deployment. Therapies cannot reach the patients who stand to benefit most if identification, referral, and biopsy remain slow or fragmented. Diagnostics, risk stratification tools, and faster biopsy pathways are prerequisites to therapeutic value, not adjuncts.

For health systems and payers, this means coordination and access are not administrative details; they shape outcomes. Delayed biopsy leads to more advanced disease, more expensive therapies, higher hospitalization rates, and earlier progression to chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Value-based models that focus narrowly on the cost of procedures fail to capture the far larger downstream costs of delay. Time-to-biopsy should be measured, tracked, and incentivized in the same way time-to-reperfusion is in cardiology or time-to-antibiotics is in sepsis.

For patient advocates, this means delay remains invisible unless someone names it. Lupus patients, especially young women of color, need to understand that kidney involvement is common, often silent, and time-sensitive. Routine urine testing is not optional. Worsening proteinuria is not something to “just watch.” Informed patients can push against system inertia, advocate for earlier referral, and demand urgency when their kidneys are at risk.

What kidneys remember

My patient eventually stabilized. Her disease came under better control. But her kidneys carry the record of every week we lost, written in fibrosis, diminished reserve, and heightened vulnerability to future flares.

She did not fail treatment. The system failed her timeline. Some organs forgive delay. Kidneys do not. They remember it. And once that story is written, no medication can unwrite it.

When it comes to kidney disease, time is tissue; and too many patients are running out of time.

###

Iqra Aftab, MD is a practicing rheumatologist in South Jersey who cares for patients with lupus and other autoimmune diseases. She is also a community builder with Docs in Tech and an expert reviewer for BMC Digital Health & AI, with a focus on connecting clinical care, technology, and patient advocacy to improve outcomes in complex diseases.

Anders, HJ., Saxena, R., Zhao, Mh. et al. Lupus nephritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 6, 7 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0141-9

Pryor KP, Barbhaiya M, Costenbader KH, Feldman CH. Disparities in Lupus and Lupus Nephritis Care and Outcomes Among US Medicaid Beneficiaries. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2021 Feb;47(1):41-53. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2020.09.004. Epub 2020 Oct 29. PMID: 34042053; PMCID: PMC8171807.

Yen EY, Singh RR. Brief Report: Lupus-An Unrecognized Leading Cause of Death in Young Females: A Population-Based Study Using Nationwide Death Certificates, 2000-2015. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 Aug;70(8):1251-1255. doi: 10.1002/art.40512. Epub 2018 Jun 27. PMID: 29671279; PMCID: PMC6105528.

Almaani, Salem; Meara, Alexa; Rovin, Brad H.. Update on Lupus Nephritis. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 12(5):p 825-835, May 2017. | DOI: 10.2215/CJN.05780616

Dooley MA, Hogan S, Jennette C, Falk R. Cyclophosphamide therapy for lupus nephritis: poor renal survival in black Americans. Glomerular Disease Collaborative Network. Kidney Int. 1997 Apr;51(4):1188-95. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.162. PMID: 9083285.

Feldman CH, Hiraki LT, Liu J, Fischer MA, Solomon DH, Alarcón GS, Winkelmayer WC, Costenbader KH. Epidemiology and sociodemographics of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis among US adults with Medicaid coverage, 2000-2004. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Mar;65(3):753-63. doi: 10.1002/art.37795. PMID: 23203603; PMCID: PMC3733212.

Contreras G, Lenz O, Pardo V, Borja E, Cely C, Iqbal K, Nahar N, de La Cuesta C, Hurtado A, Fornoni A, Beltran-Garcia L, Asif A, Young L, Diego J, Zachariah M, Smith-Norwood B. Outcomes in African Americans and Hispanics with lupus nephritis. Kidney Int. 2006 May;69(10):1846-51. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000243. PMID: 16598205.

Dooley MA, et al.

Contreras G, et al.

Koppula S, Patel K, Unruh M. The Delivery of Kidney Care in Rural or Sparsely Populated Settings. Am J Kidney Dis. 2025 Oct;86(4):543-549. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2025.03.017. Epub 2025 Apr 29. PMID: 40311667.

Cass A, Cunningham J, Snelling P, Ayanian JZ. Late referral to a nephrologist reduces access to renal transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003 Nov;42(5):1043-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajkd.2003.07.006. PMID: 14582048.

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IXc-!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9f7142a0-6602-495d-ab65-0e4c98cc67d4_450x450.png)

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lBsj!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_48,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0e0f61bc-e3f5-4f03-9c6e-5ca5da1fa095_1848x352.png)