Signals Brief: Should Primary Care Drive CKD Screening?

"Yes. And…" Here’s what three other strategies can teach us.

TL;DR

Early detection of CKD is critical — but where and how we screen matters. This brief breaks down four core strategies for CKD screening: primary care, community events, employer-based models, and mobile outreach. Each offers unique advantages and limitations, from clinical integration to equity impact, cost, and scalability. Drawing from real-world programs like CKDintercept, the VA C3 initiative, KEEP, La Isla Network, and more, we map out the evidence, challenges, and lessons learned. We also share a visual comparison grid for subscribers to help identify tradeoffs, gaps, and high-impact opportunities.

In This Brief

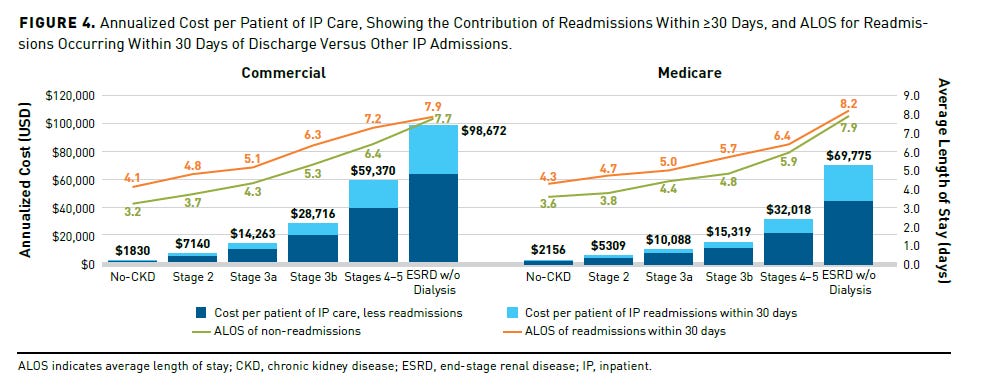

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects nearly 1 in 10 adults globally, yet most people who have it don’t know it. In the U.S., it’s one of the most underdiagnosed and undertreated chronic conditions — despite being a major driver of cardiovascular events, in-hospital complications, early death, and rising healthcare costs. In 2022 alone, Medicare spent more than $86 billion managing CKD — over one quarter of its fee-for-service budget. The problem isn’t just the burden of advanced kidney disease. It’s that we’re still missing people in the early, more treatable stages.12

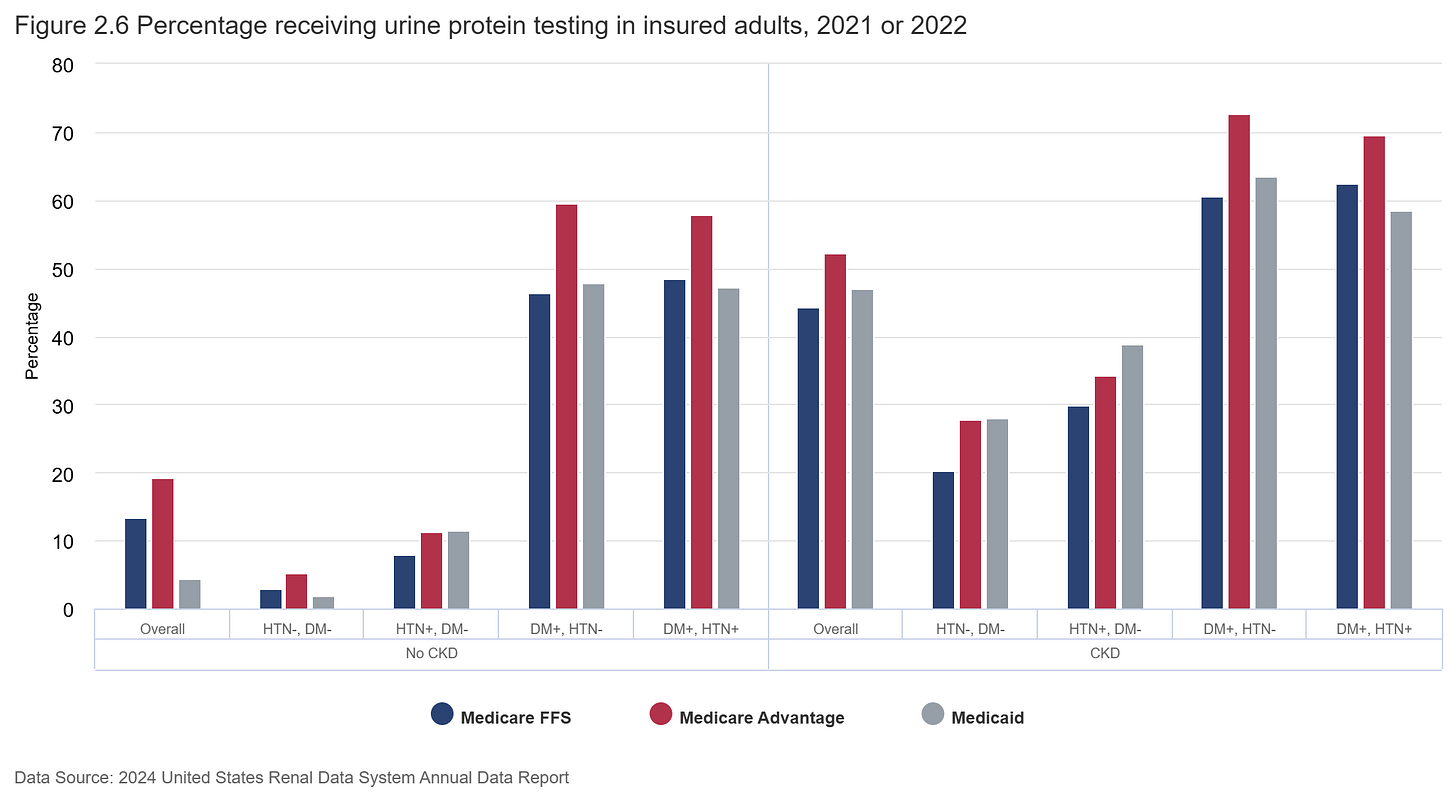

Screening for CKD — typically done via estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) tests — is recommended for high-risk groups, but rarely happens in practice. Fewer than half of people with diabetes receive both tests, and among those with hypertension but no diabetes, albuminuria is routinely checked in less than 10%. That’s despite strong evidence that early detection and staging can reduce downstream complications, support better cardiovascular risk stratification, and improve referrals and treatment. The result is a persistent evidence-to-care gap, where opportunities for prevention are lost before they begin.3

And while guidelines are clear, implementation is not. Primary care providers, often the front line of chronic disease management, report limited time, low confidence in CKD care, and little institutional support for improvement efforts. Even in health systems that do regularly screen, there’s substantial variation in how results are interpreted and acted upon. In that context, CKD screening is not just about a test, it’s about where and how that test fits into a system of care.

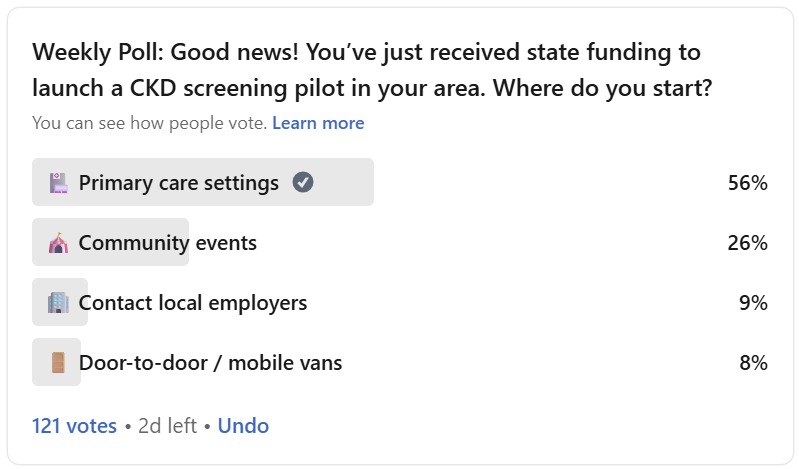

That’s why I posed this question to the Signals community: Where should we start? My recent LinkedIn poll asked people to choose the most promising strategy to drive CKD screening at scale. While most pointed to primary care, the comment thread revealed deeper tensions: between population reach and follow-up feasibility, between clinical infrastructure and community trust, and between aspirational ideas and operational realities. This brief unpacks those tradeoffs, explores what it takes to launch effective CKD screening programs, and highlights lessons from those who have already walked this path.

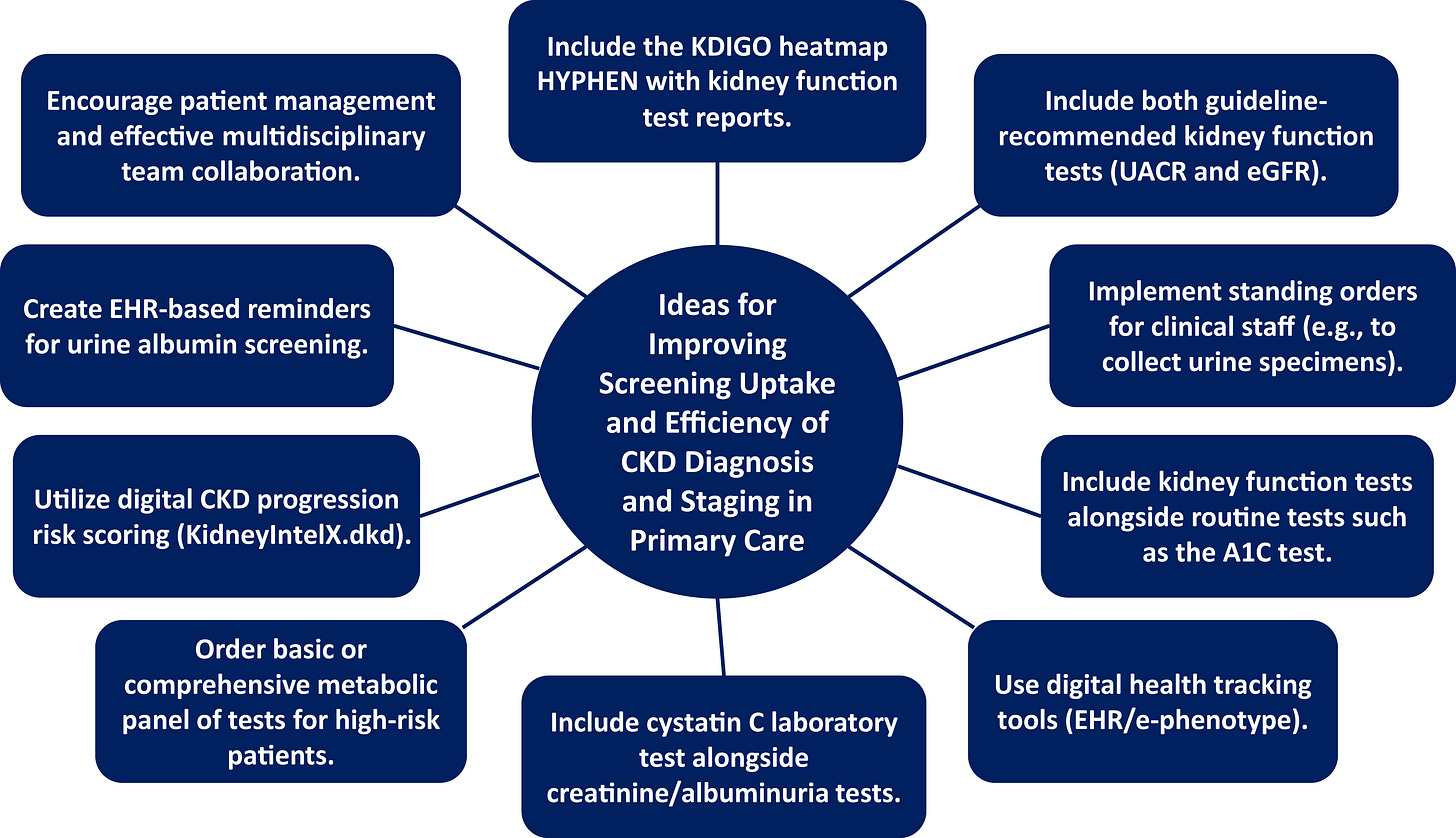

1. Primary Care Settings

Primary care is where screening makes the most clinical and operational sense — but it’s also where time and incentives are the tightest. Many respondents emphasized this approach, with comments pointing to the ability to leverage existing lab work, chronic care pathways, and EHR infrastructure. Many in the community pointed to this setting as the logical starting point, noting its ability to leverage existing lab work, chronic disease management workflows, and EHR infrastructure. For patients with diabetes, hypertension, or cardiovascular disease, routine visits create natural opportunities to test for CKD using estimated GFR and urine ACR — tests that are inexpensive, widely available, and already embedded in many care pathways.

But implementation is often hindered by fragmented workflows, limited provider awareness, and lack of system-level support. Nearly 80% of patients with moderate CKD have no formal diagnosis in their medical record, and almost half of those with advanced CKD remain undocumented. Even when tests are ordered, results may not be interpreted or acted upon in a timely way, a reflection of both knowledge gaps and structural barriers in care delivery.4

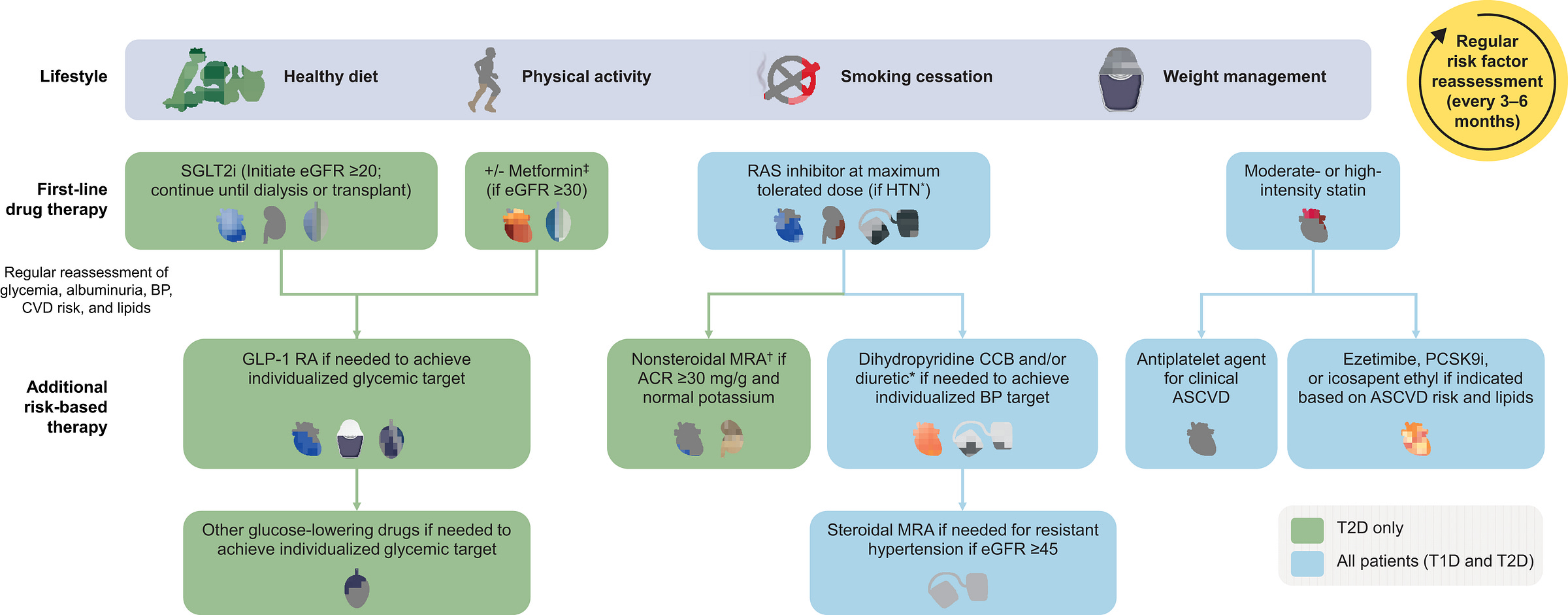

Recent guidelines have tried to close this gap. A recent Clinical Diabetes paper proposed a risk-aligned treatment algorithm for people with type 2 diabetes and CKD, starting with annual screening using eGFR and ACR. The algorithm stratifies patients by albuminuria level, guiding the use of therapies like SGLT2 inhibitors and MRAs to reduce kidney and cardiovascular risk. But that entire framework still hinges on one thing: early detection.

Some health systems are starting to respond, integrating CKD prompts into their EHRs, adopting the Kidney Health Evaluation (KED) HEDIS measure, and applying population health tools to identify gaps. Still, many respondents noted that clinical bandwidth remains limited, and incentives misaligned. Perhaps primary care can and should be the engine of early CKD detection— but only if screening becomes easier to do, harder to overlook, and more clearly recognized and rewarded across the system.5

2. Community Events

Community-based screening may not reach the same volume as primary care, but it offers something just as important: visibility, trust, and access in places the system often misses. Contributors emphasized the importance of meeting people where they are — at health fairs, churches, workplaces, or neighborhood events. These outreach efforts are especially valuable for reaching people without regular access to care, or who may not engage with the healthcare system until disease is advanced.

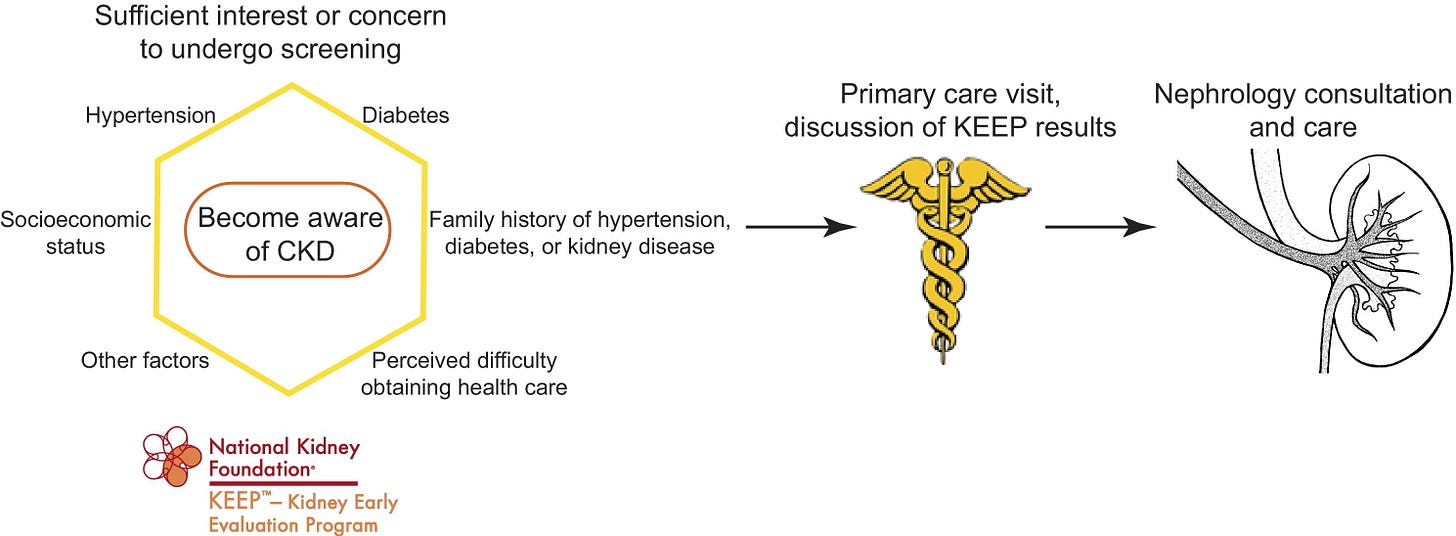

The National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) illustrated both the scale and the limits of this approach. From 2000 to 2013, KEEP provided free testing, education, and referrals to more than 185,000 high-risk individuals across the U.S., including those with diabetes, hypertension, or a family history of kidney failure. KEEP not only increased CKD awareness among underserved populations — it also produced rich longitudinal data that deepened our understanding of barriers to care. Participants frequently reported difficulty accessing healthcare or nephrology services, and many had never discussed kidney risk with a provider. Interestingly, those who perceived greater barriers were also more likely to be aware of CKD — highlighting how concerns about access can drive engagement. KEEP’s impact was not just in screening, but in surfacing the complex intersection between awareness, access, and action.6

Its successor, KEEP Healthy, shifted focus from screening to education, helping people understand kidney risk factors and prevention strategies. Both initiatives demonstrate the enduring value of starting with trust and awareness, especially in populations historically underserved by the healthcare system.

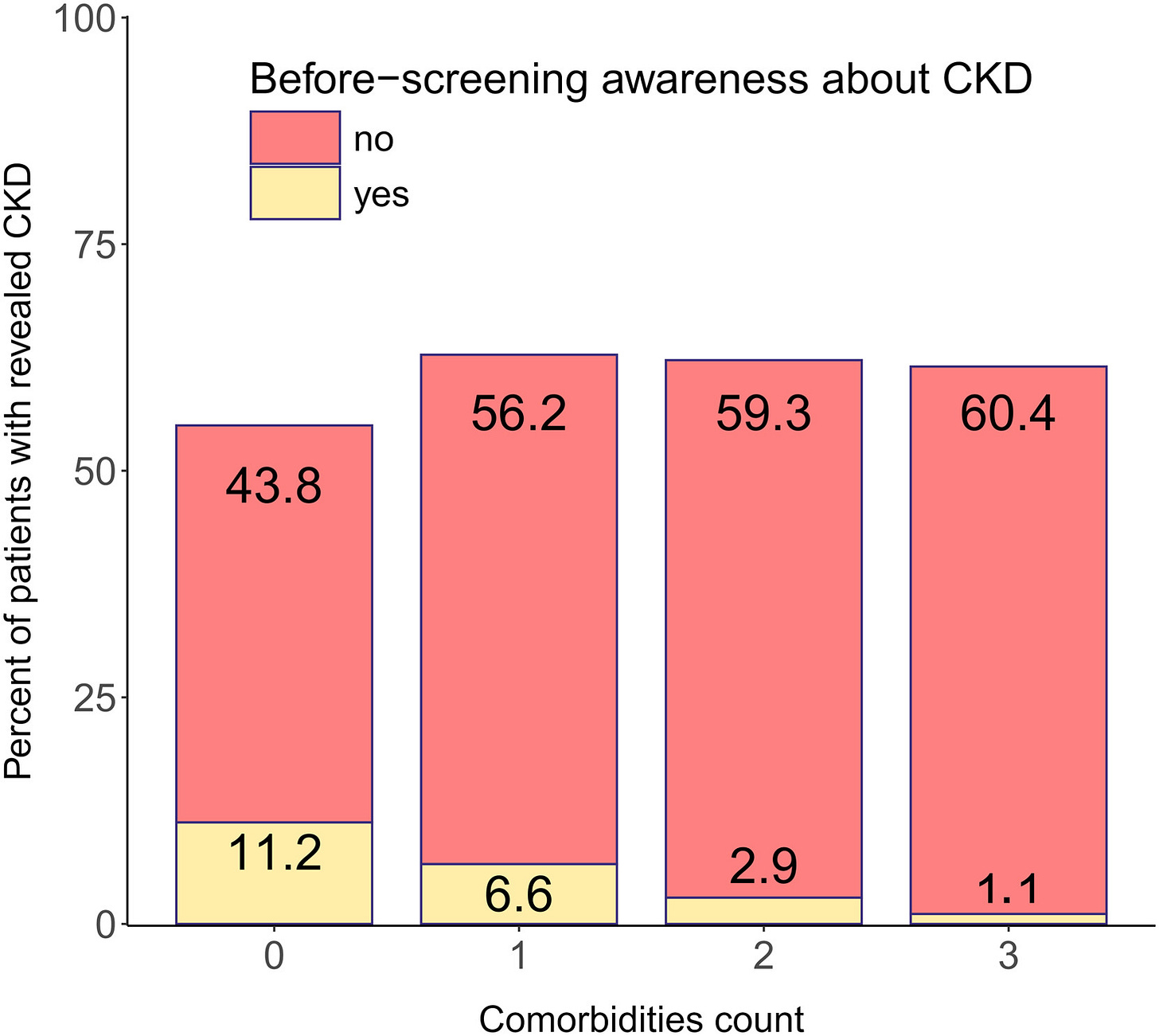

Newer models are now building on this foundation. A recent pilot study in India used point-of-care testing (POCT) for creatinine and urine ACR, combined with digital health tools, to screen over 2,000 people in urban and rural settings. The results were striking: CKD was found in over 60% of those screened in rural areas, most of whom had no prior diagnosis — and nearly half had no comorbidities. Only 16.5% were aware they had CKD, despite many being in later stages of the disease. This model showed how POCT and mobile-enabled referrals can overcome infrastructure gaps and deliver scalable, high-yield screening in high-risk, low-access populations.

When done well, community screening becomes a lower-barrier, higher-trust front door to care. But for it to succeed, it must be designed with continuity in mind — including strong referral systems, culturally informed engagement, and technology that tracks and supports patients beyond the event itself. We can also draw insights from population-level screening studies, which consistently show that cost-effectiveness and impact hinge on targeting the right individuals, and delivering the right tests in the right settings. As these models evolve, they hold real promise not only for raising awareness, but also for reducing disparities in early detection and outcomes.7

3. Employer-Based Screening

Screening at the workplace offers a pragmatic channel for early detection— and a massive, often overlooked opportunity in certain industries. While only a small percentage of respondents selected this option in our poll, several pointed to its untapped potential: employers capture health data, often bear the financial burden of chronic disease, and have a direct interest in preserving worker productivity. This is especially true in self-insured settings and industries with high exposure to environmental or occupational risk factors.

In agricultural and labor-intensive industries, for example, chronic kidney disease of non-traditional origin (CKDnt) has become a public health crisis. In Central America, some agricultural communities report CKD prevalence rates exceeding 40% among male workers. Through its PREP initiative, the La Isla Network has shown that workplace improvements — including hydration, shaded rest, and workload adaptation — not only reduce kidney injury and mortality, but deliver up to a 22% return on investment. As global temperatures rise, these findings are becoming relevant far beyond the sugarcane fields.

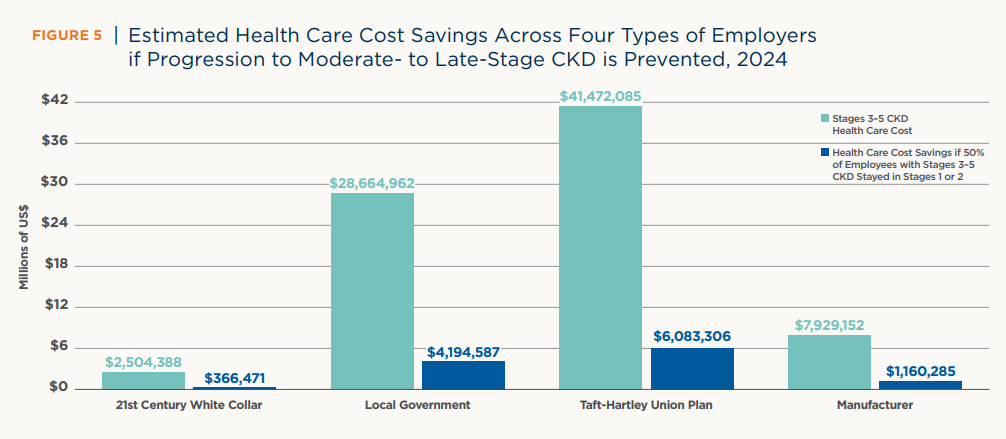

In the U.S., the employer burden is different — but just as urgent. According to a 2024 analysis by the American Kidney Fund, employees with moderate- to late-stage CKD (stages 3–5) account for only 1% of the workforce but drive 8% of annual employer healthcare costs, totaling over $107 billion annually. If employers could delay progression through earlier intervention and targeted benefits, they could save up to $35 billion in healthcare costs per year — not including productivity gains. In industries like manufacturing and local government, per-employer savings could reach millions annually.8

U.S.-based employers are already feeling the financial and workforce impact of CKD — but they also hold the power to change the trajectory. Between 2006 and 2014, more than 68,000 people with CKD left the workforce within six months of developing kidney failure. Yet many individuals with early-stage CKD (stages 1–3) can continue working — and with the right support, delay or even avoid disease progression. Early detection and accommodations are not only a legal obligation under the ADA, but a strategic investment in workforce health. Employers can take action by integrating kidney health into workplace screenings, partnering with chronic care management programs, or offering benefits that cover guideline-recommended testing. These steps reduce high-cost claims, improve employee retention, and support a more resilient, productive workforce — especially since 53% of people with CKD are of working age and depend on employer-sponsored insurance for access to care.9

In short, the workplace is both a risk environment and an opportunity zone. Employers that act early can protect their teams, reduce preventable spending, and reshape kidney health outcomes.

4. Door-to-Door & Mobile Screening

When traditional healthcare settings fall short, mobile and door-to-door approaches can bridge the gap — especially in rural, remote, or underserved areas. These models rely on trusted messengers and familiar environments, lowering barriers to care and increasing the likelihood of early detection. Several programs show what’s possible when screening meets people where they are.

In rural Michigan, a mobile health initiative led by Michigan State University partnered with community health workers to deliver kidney education and screenings. Through culturally tailored outreach and consistent follow-up, the team identified early-stage CKD in individuals with limited access to care — raising screening rates by 27% among patients with diabetes and 17% among those with hypertension.

In Manitoba, Canada, the FINISHED Project brought point-of-care testing to 11 First Nations communities. Nearly 1,500 individuals were screened using rapid diagnostics, real-time risk prediction, and immediate referrals. All intermediate- and high-risk patients were seen by a nephrologist within one month — demonstrating that mobile, culturally grounded screening can deliver immediate impact where it’s needed most.10

In Kerala, India, the Kidney Disease Screening (KIDS) Project screened over 2,000 adults in rural Karnataka through household visits conducted by trained nursing students. Using both blood and urine testing, the program found that 6.3% of participants met criteria for CKD—comparable to urban prevalence rates. Notably, over half of participants with CKD had no proteinuria, highlighting the need for serum creatinine testing alongside urine dipsticks. Less than 10% of end stage renal disease (ESRD) patients in this area have access to any kind of renal replacement therapy.11

In rural Guatemala, the nonprofit Wuqu’ Kawoq (Maya Health Alliance) screened patients in a community-based diabetes cohort, uncovering a 57% CKD prevalence rate, with nearly 1 in 5 at high or very high risk of progression. The initiative showed the feasibility of KDIGO-aligned screening in remote villages, but also highlighted key barriers: testing costs, fragile logistics, and limited guidance for implementation in resource-constrained settings. The study called for greater global collaboration to adapt screening protocols to local realities and make early detection more sustainable.12

When designed with community input, these models can serve as lasting front doors to care— not just one-off interventions. But their success hinges on strong referral systems, longitudinal follow-up, and the infrastructure to track outcomes over time.

Bringing It Together

Everyone seems to agree: this isn’t about choosing one strategy, it’s about building a system. CKD screening is more than a lab test, it’s the first step in a coordinated care cascade. And while it’s easy to debate which setting is “best,” it’s clear that real-world success often depends on how strategies are layered and aligned in current workflows. Screening is only useful if it’s paired with risk stratification, education, follow-up, and referral. That’s why efforts that transcend silos— across clinics, payers, public health, and communities— are so valuable.

Two efforts stand out for how they approached this challenge at scale.

Case Study 1: Show Me CKDintercept in Missouri

In a state where nearly 700,000 people are estimated to have CKD, but fewer than 17% of at-risk adults are tested annually, the Show Me CKDintercept initiative aimed to flip the script. Launched by the National Kidney Foundation and state partners, the initiative brought together 159 stakeholders from 81 organizations— including health systems, payers, public health departments, and community groups— to co-develop a roadmap for early detection and management. After 16 hours of facilitated discussion, 58 stakeholders identified 12 strategies to improve testing, diagnosis, and early management of CKD in Missouri and across the United States.13

The initiative centered health equity from the start, prioritizing input from groups serving historically underserved populations. It also piloted innovative tools — like at-home test kits, community pharmacy-based screening, and CKD education for frontline workers — to expand awareness and testing. While long-term impact is still being tracked, Missouri’s work provides a replicable model for other states: one that treats CKD detection as a public health opportunity rather than a private clinical task.

Case Study 2: The C3 Initiative at the VA

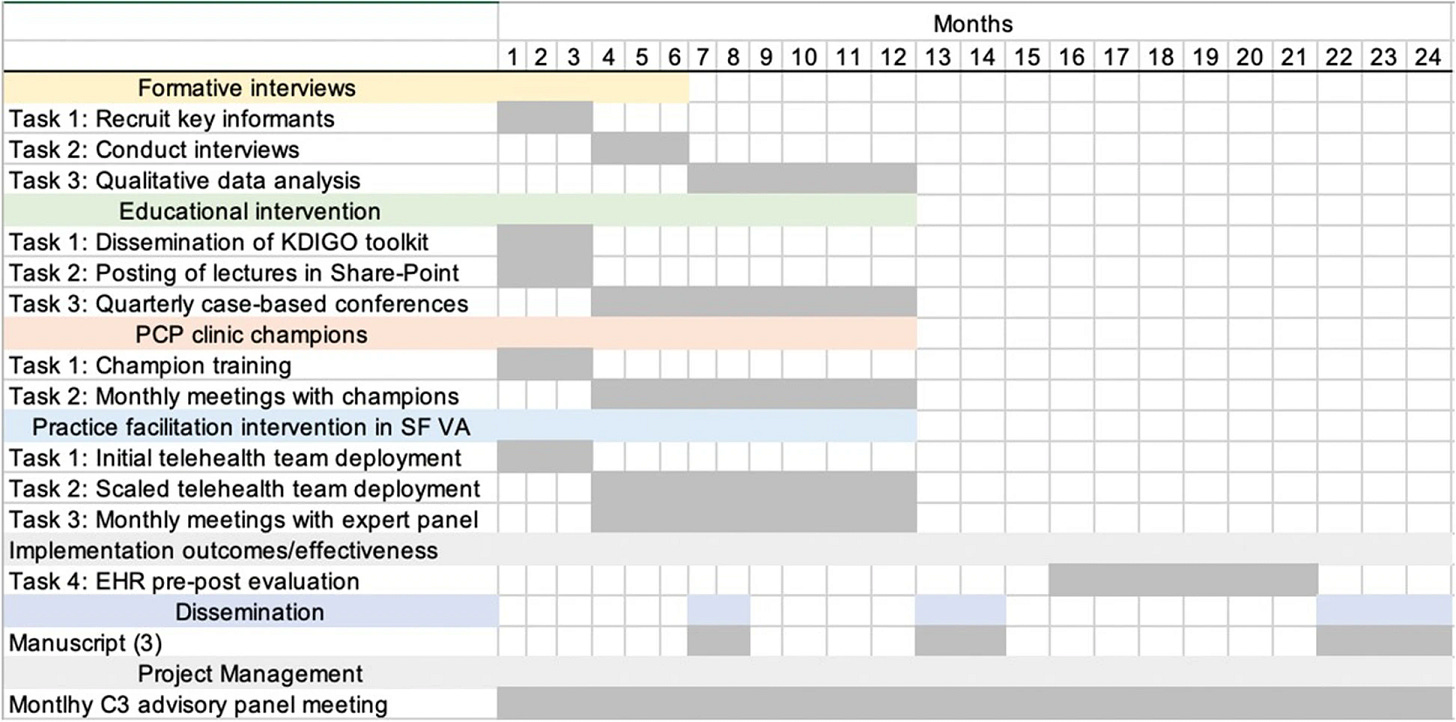

The Chronic Kidney Disease Cascade of Care (C3) initiative was launched across three major VA medical centers — San Francisco, San Diego, and Houston — in response to a 2020 VA directive aimed at improving early detection and management of CKD. Over 820,000 Veteran users of the VHA already meet criteria for CKD diagnosis. Built on patient-centered primary care teams (PACTs), C3 is one of the first system-level efforts to integrate triple-marker screening into routine primary care for high-risk patients with diabetes, hypertension, or cardiovascular disease.14

What sets C3 apart is its inclusion of cystatin C testing alongside serum creatinine and urine ACR — a key recommendation in the VA/DoD guidelines but rarely implemented in practice. San Francisco led the effort, establishing internal lab capacity and helping other VA sites do the same. Through coordination with local lab leaders and national partners, both San Diego and Houston validated and launched cystatin C testing on-site, enabling real-time triple-marker screening across more than 100 primary care providers.

The initiative is evaluating both testing rates and downstream outcomes, including use of cardio-kidney protective therapies and appropriate nephrology referrals. It also incorporates clinic champions, practice facilitation, and provider education to support behavior change. While results are still being measured, C3 demonstrates how a large, integrated health system can turn national screening recommendations into operational practice— with potential lessons for broader primary care transformation.

The Bottom Line

There’s no single solution for early CKD detection — but there’s a growing recognition that we need to act sooner, smarter, and more equitably. Primary care remains a logical starting point, yet structural barriers, competing demands, and misaligned incentives have slowed adoption. Community-based and mobile models offer visibility and trust, especially in underserved populations. Employer-based strategies are gaining momentum, driven by rising costs and a growing awareness of CKD’s impact on workforce health. And door-to-door efforts, while labor-intensive, show what’s possible when care shows up— even in the hardest-to-reach corners.

There’s also growing alignment on what good detection looks like. While not a broad screening recommendation, the Kidney Health Evaluation for Patients with Diabetes (KED) measure provides a baseline: combined testing of eGFR and quantitative urine ACR to evaluate kidney health in adults with diabetes. Yet despite this progress, CKD screening is not universally recommended — and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force still finds “insufficient evidence” to support routine screening in asymptomatic adults. That gap continues to shape awareness, investment, and adoption of quality measures.15

If you’re working on new models of early detection, engagement or education, we’d love to hear from you. Share your company or initiative here, or let us know what unmet needs you’re seeing on the ground here. We’re building a new directory to spotlight what’s working— and what still needs support— across the kidney community.

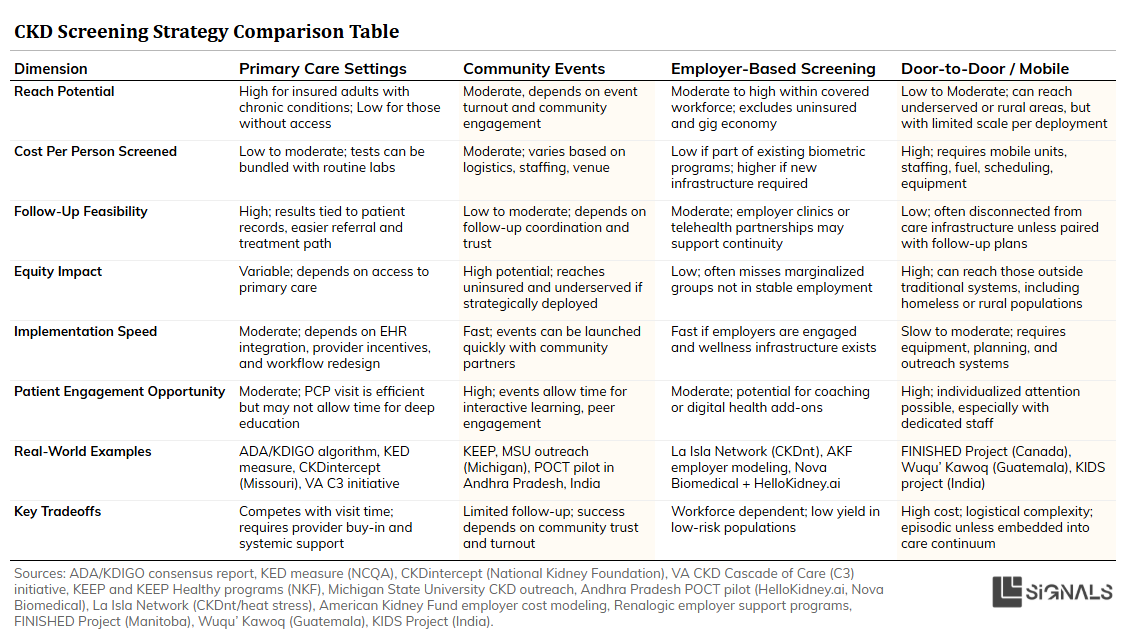

Visual Summary

We've covered a lot of ground. If you're looking for a quick side-by-side comparison of each approach— with summaries of strengths, weaknesses, examples, and implementation tips— I’ve pulled together a visual chart below.

A side-by-side look at four key approaches to early CKD detection—covering strengths, challenges, real-world examples, and tips for implementation. Use this as a quick reference to understand what works where, and why.

GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2020 Feb 29;395(10225):709-733. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30045-3. Epub 2020 Feb 13. PMID: 32061315; PMCID: PMC7049905.

United States Renal Data System. 2024 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD, 2024.

Ferrè S, Storfer-Isser A, Kinderknecht K, et al. Fulfillment and validity of the Kidney Health Evaluation measure for people with diabetes. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2023;7(5):382–391. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2023.07.002

Diamantidis CJ, Hale SL, Wang V, Smith VA, Scholle SH, Maciejewski ML. Lab-based and diagnosis-based chronic kidney disease recognition and staging concordance. BMC Nephrol. 2019 Sep 14;20(1):357. doi: 10.1186/s12882-019-1551-3. PMID: 31521124; PMCID: PMC6744668.

Szczech LA, Stewart RC, Su HL, DeLoskey RJ, Astor BC, Fox CH, McCullough PA, Vassalotti JA. Primary care detection of chronic kidney disease in adults with type-2 diabetes: the ADD-CKD Study (awareness, detection and drug therapy in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease). PLoS One. 2014 Nov 26;9(11):e110535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110535. PMID: 25427285; PMCID: PMC4245114.

Ferrè S, Storfer-Isser A, Kinderknecht K, Montgomery E, Godwin M, Andrews A, Dunning S, Barton M, Roman D, Cuddeback J, Stempniewicz N, Chu CD, Tuot DS, Vassalotti JA. Fulfillment and Validity of the Kidney Health Evaluation Measure for People with Diabetes. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2023 Aug 29;7(5):382-391. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2023.07.002. PMID: 37680649; PMCID: PMC10480072.

Whaley-Connell AT, Vassalotti JA, Collins AJ, Chen SC, McCullough PA. National Kidney Foundation's Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) annual data report 2011: executive summary. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012 Mar;59(3 Suppl 2):S1-4. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.11.018. PMID: 22339897; PMCID: PMC3285421.

Powe NR, Boulware LE. Population-based screening for CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009 Mar;53(3 Suppl 3):S64-70. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.07.050. PMID: 19231763; PMCID: PMC2681232.

The Impact of Chronic Kidney Disease on the Workforce (Renalogic, January 2025)

Lavallee B, Chartrand C, McLeod L, Rigatto C, Tangri N, Dart A, Gordon A, Ophey S, Komenda P. Mass screening for chronic kidney disease in rural and remote Canadian first nations people: methodology and demographic characteristics. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2015 Mar 19;2:9. doi: 10.1186/s40697-015-0046-9. PMID: 27408755; PMCID: PMC4940863.

Anupama YJ, Uma G. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease among adults in a rural community in South India: Results from the kidney disease screening (KIDS) project. Indian J Nephrol. 2014 Jul;24(4):214-21. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.132990. PMID: 25097333; PMCID: PMC4119333.

Flood D, Garcia P, Douglas K, Hawkins J, Rohloff P. Screening for chronic kidney disease in a community-based diabetes cohort in rural Guatemala: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018 Jan 21;8(1):e019778. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019778. PMID: 29358450; PMCID: PMC5781190.

Laue K, Schultz M, Talbot-Montgomery E, Garrick A, Java A, Corbett C, Lammert DM, Rogers J, Davis K, Malhotra K, Philipneri M, Kimbel MA, Mustafa RA, Hardesty V. Show Me CKDintercept Initiative: A Collective Impact Approach to Improve Population Health in Missouri. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2024 Jan 12;8(1):82-96. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2023.12.004. PMID: 38283097; PMCID: PMC10821387.

Executive Summary: Ending Disparities in CKD Leadership Summit – Missouri

Lamprea-Montealegre JA, Joshi P, Shapiro AS, Madden E, Navarra K, Potok OA, Gregg LP, Podchiyska T, Robinson A, Goldstein MK, Peralta CA, Jassal SK, Navaneethan SD, Rifkin DE, Wang V, Shlipak MG, Estrella MM. Improving chronic kidney disease detection and treatment in the United States: the chronic kidney disease cascade of care (C3) study protocol. BMC Nephrol. 2022 Oct 12;23(1):331. doi: 10.1186/s12882-022-02943-z. PMID: 36224528; PMCID: PMC9554861.

The KED measure, launched in 2023, monitors kidney health in people with diabetes by requiring quantitative testing of both eGFR and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (uACR) during the measurement year. Its goal is to identify risk and prevent CKD progression — but it is not intended to serve as a general screening measure. The measure excludes semi-quantitative urine tests (e.g., dipsticks) unless followed by confirmatory lab-based testing, as these are insufficient for diagnosis or risk staging.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) — an independent panel — has not issued a formal recommendation for routine CKD screening in asymptomatic adults, citing a lack of evidence. However, some experts have argued that a positive recommendation could drive greater awareness, improve quality measure alignment, and support earlier detection through better policy and reimbursement structures.

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IXc-!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9f7142a0-6602-495d-ab65-0e4c98cc67d4_450x450.png)

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lBsj!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_48,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0e0f61bc-e3f5-4f03-9c6e-5ca5da1fa095_1848x352.png)