Today’s guest is Dr. Ben Hippen, Global Head of Clinical Affairs and Chief Medical Officer for Care Delivery at Fresenius Medical Care. He’s here to talk about transplant policy, the rise of GLP-1s, and the future of CKD care—but naturally, that was way too much to tackle in one sitting. So in this first conversation, we focused entirely on transplant.

Ben and I first connected at ATC last year, shortly after he published his paper in Kidney International Reports laying out a transplant-inclusive value-based kidney care payment model alongside co-authors Drs. George Hart and Frank Maddux. That paper made quite a splash, and stood out as one of the most detailed and thoughtful frameworks for reimagining transplant care I’d seen—clear-eyed, systems-oriented, and grounded in real-world experience.1

There’s a lot we weren’t able to cover, like where ETC’s aims fell short, what the recent NYT transplant investigation got wrong (and right), and what a great kidney policy outcome might look like in the second Trump Administration and beyond. But I know you’ll still enjoy this conversation, and there’s more to come.

Signals KOLs is the series that highlights key opinion leaders whose work is shaping the future of kidney health across industry, academia, policy, research, advocacy, and beyond.

My List of Questions:

What does the IOTA rule actually change for transplant centers?

Will it really lead to more transplants—or just more metrics?

What’s the story behind that “one in six” referral stat?

Why do so many patients fall through the cracks—and what can be done about it?

Where does Medicare Advantage fit in here? How will it impact kidney care?

Q&A

Watch or listen to the full video interview above. The Q&A-style interview below is lightly edited for brevity and flow.

Q: For those who are newer to the IOTA rule—what’s the quick version?

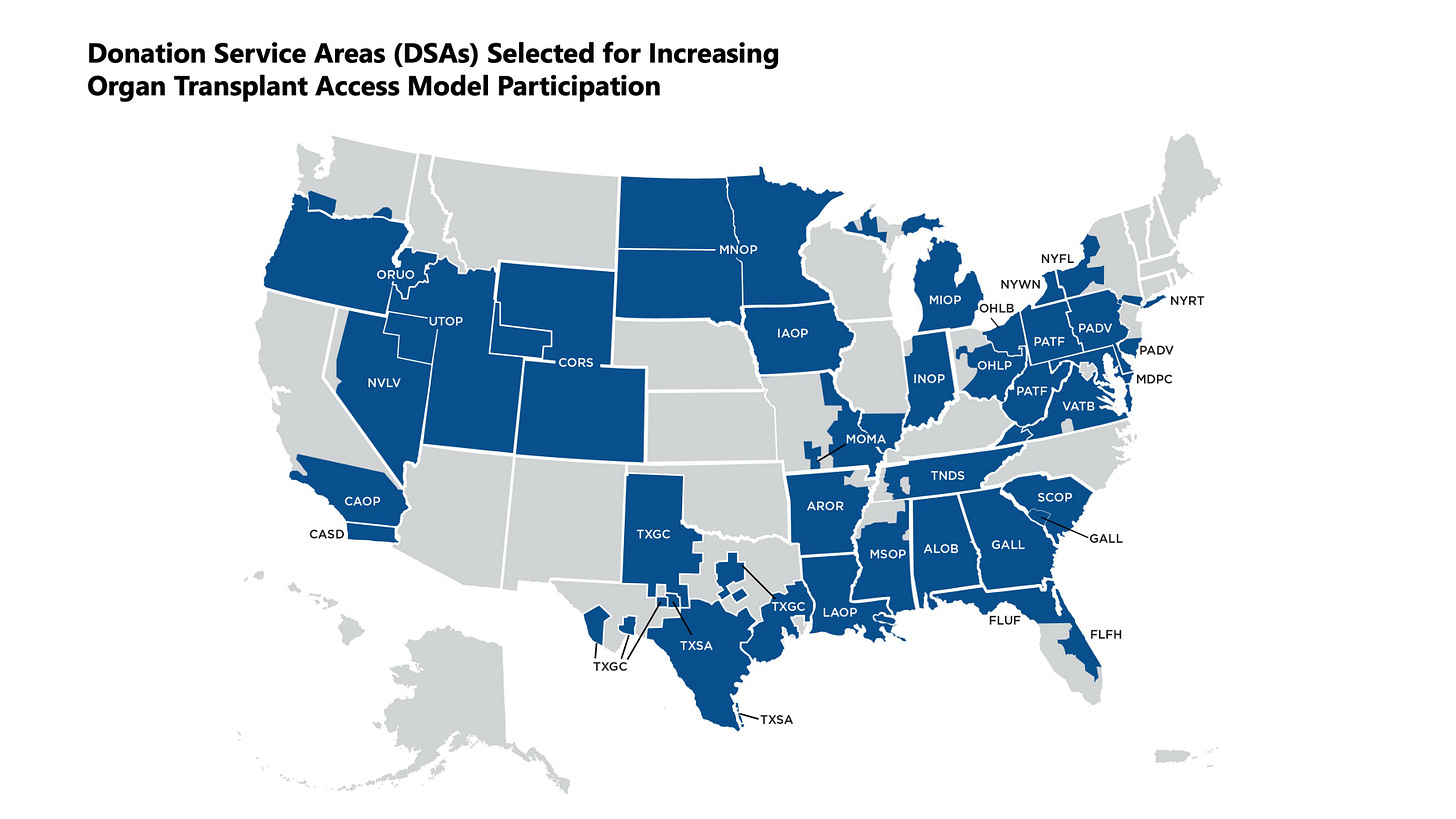

BH: I think of IOTA as a version of the ESRD Treatment Choices (ETC) model but specifically for transplant centers. It only applies to the 103 centers included—nephrologists and dialysis providers aren’t part of it. It also doesn’t include OPOs.

There are three performance domains:

Achievement – transplant volume, and it’s overweighted.

Efficiency – how often a center accepts organ offers.

Quality – longer-term graft survival.

What’s really different here is the focus on volume. For the last 15 years, transplant policy has over-indexed on short-term survival metrics. That discouraged centers from taking risks on higher-risk donors and candidates. IOTA shifts the focus back to getting more transplants done.23

Figure: Half of DSAs Selected for Mandatory Model

Q: Transparency was a big part of the proposal. What made it into the final rule?

BH: There were two major transparency components. One survived, one didn’t.

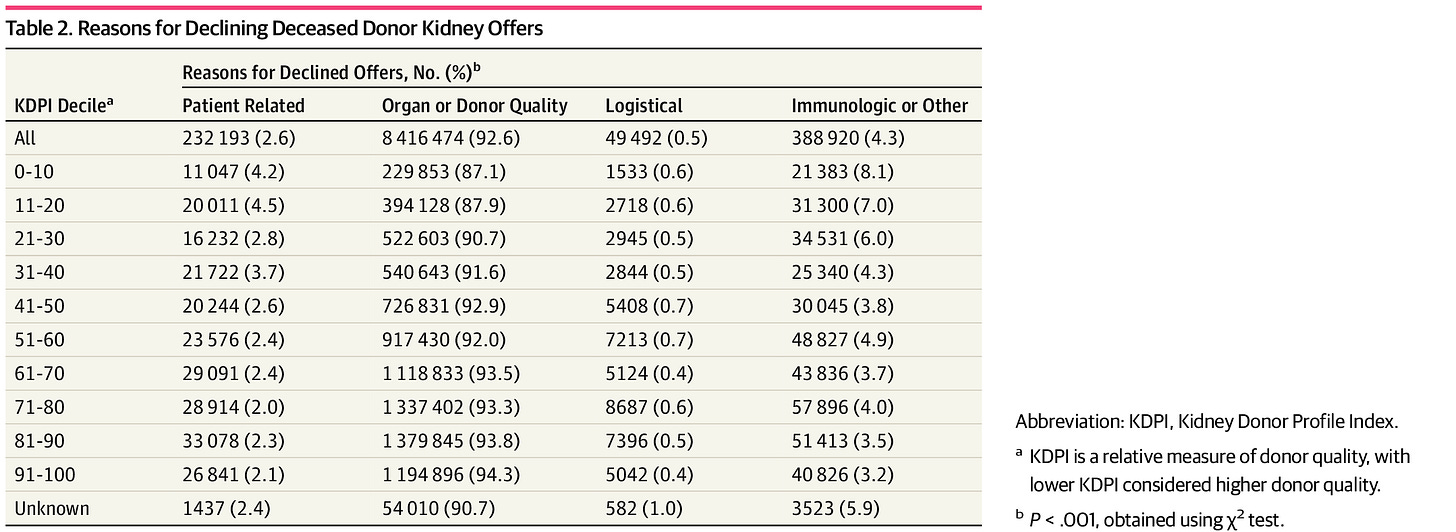

The one that made it in requires centers to publicly disclose their organ offer selection criteria. That’s a win. It encourages centers to be thoughtful and clear about how they accept or decline offers.

The other proposal—that candidates should be notified when an organ was declined on their behalf—didn’t survive. There were real concerns about how operationally feasible that would be. Offers are often made to hundreds of candidates at once, and it wasn’t clear how to make that disclosure meaningful without overwhelming or confusing patients.

Figure: Reasons for Declining Deceased Donor Kidney Offers4

Q: IOTA also touches on organ offer filters. What are they, and why does that matter?

BH: Transplant centers can use filters in the UNet system to automatically decline organs that don’t meet their criteria. When done thoughtfully, it improves efficiency—centers only see offers they might actually accept.5

The model acknowledges that. If you use filters, you’re only judged on the offers that pass through them, which can help your efficiency score. But there’s a trade-off: if you filter too aggressively, your transplant volume might go down, which hurts your achievement score. It’s a clinically appropriate tension, and I think the model handles it well.

Q: Are the incentives strong enough to move behavior?

BH: Financially, the bonuses and penalties are modest.6 They probably won’t change a transplant program’s P&L. But the reputational impact—how your center performs in IOTA will be publicly reported—that might matter more.

So the bigger signal here is the policy direction. IOTA points toward a future where transplant is part of a broader, longitudinal value-based care model that spans CKD, dialysis, and post-transplant care. That’s where we need to go.

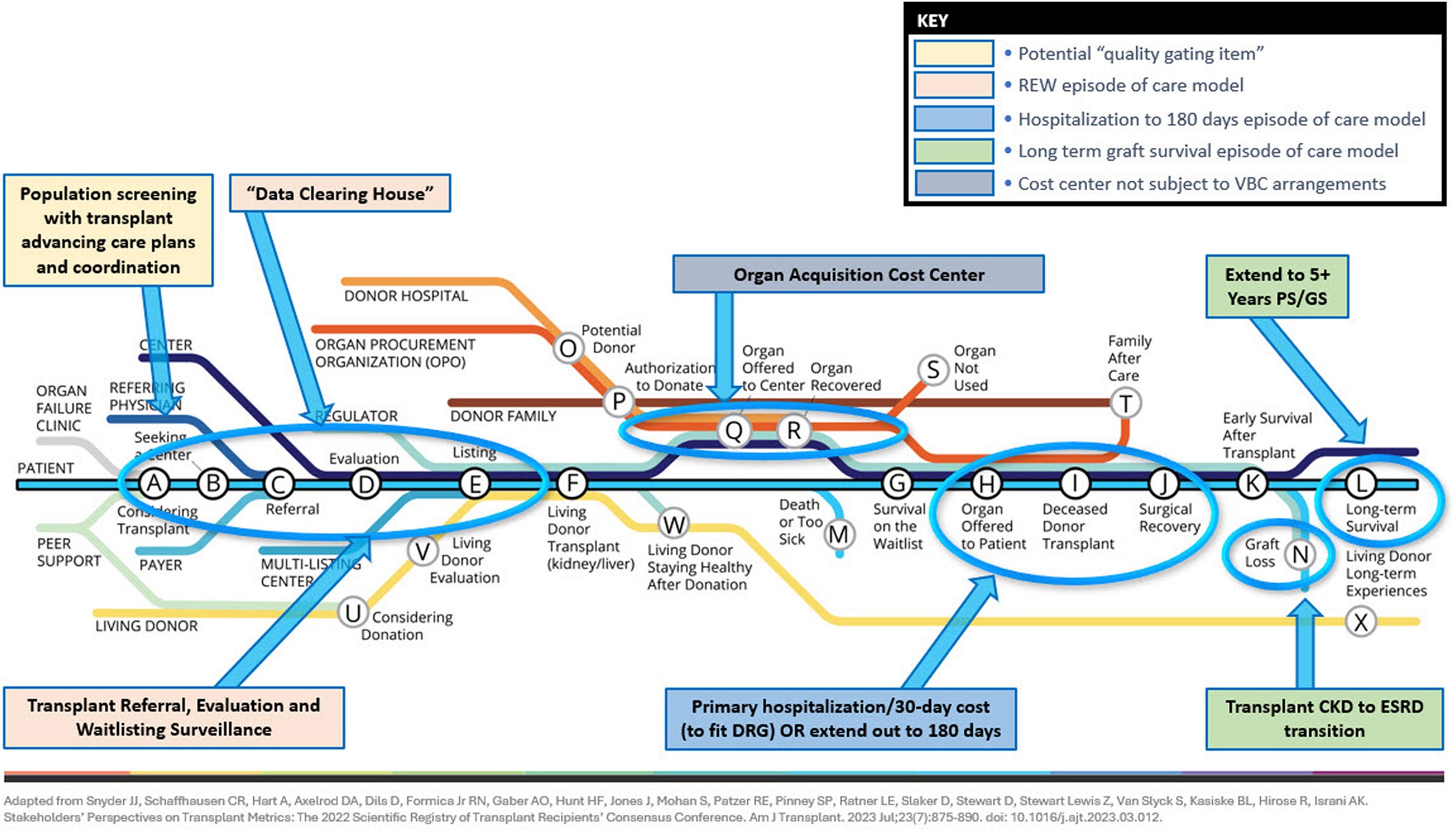

Figure: A Transplant-Inclusive Value-Based Care Model

Q: How did you get involved in this work?

BH: I was a practicing transplant nephrologist in Charlotte. One day, a dialysis patient asked me where they stood in the transplant process. I had referred them, but it wasn’t easy to find out what happened next. I had to call a contact at the center and dig.

That moment stuck with me. It revealed just how many invisible breakdowns exist in the system. It got me thinking about how fragmented kidney care really is—and how much room we have to build something better.

Q: You mentioned some pretty striking data about transplant referrals. Can you walk us through that?

BH: Sure. There’s a study from a few years ago published in CJASN that looked at patients referred for transplant at nine centers across ESRD Network 6—Georgia, North and South Carolina. What they found was this:

Only 50% of referred patients began evaluation within six months.

Of those, only 30% made it to the waitlist within a year.

That means only about 1 in 6 patients referred for transplant actually end up on the waitlist within a year. And we don’t really know why the rest don’t make it. That lack of visibility is what we’re trying to address.7

Q: That leads into the work you’ve been leading at Fresenius. What’s the initiative you’re most proud of?

BH: I’d say it’s our work to standardize the transplant referral process. There are 256 kidney transplant programs in the U.S.—and nearly 256 different ways to refer a patient. Many referrals are still faxed, often filled out by hand. You can imagine how much gets lost in that process.

We built a platform that streamlines it. With a few clicks, we auto-generate a referral form that includes 167 demographic, clinical, psychosocial, lab, and regulatory data points—all in an intuitive format we co-designed with transplant coordinators and social workers. We've already increased our new transplant referrals by about a third over the last two years.

Of course, it doesn’t solve the whole problem—we still face the “one in six” issue—but it’s a foundational step. And now, we’re looking for ways to partner with transplant centers to better understand what happens to the other five patients and how we can keep them from falling through the cracks.

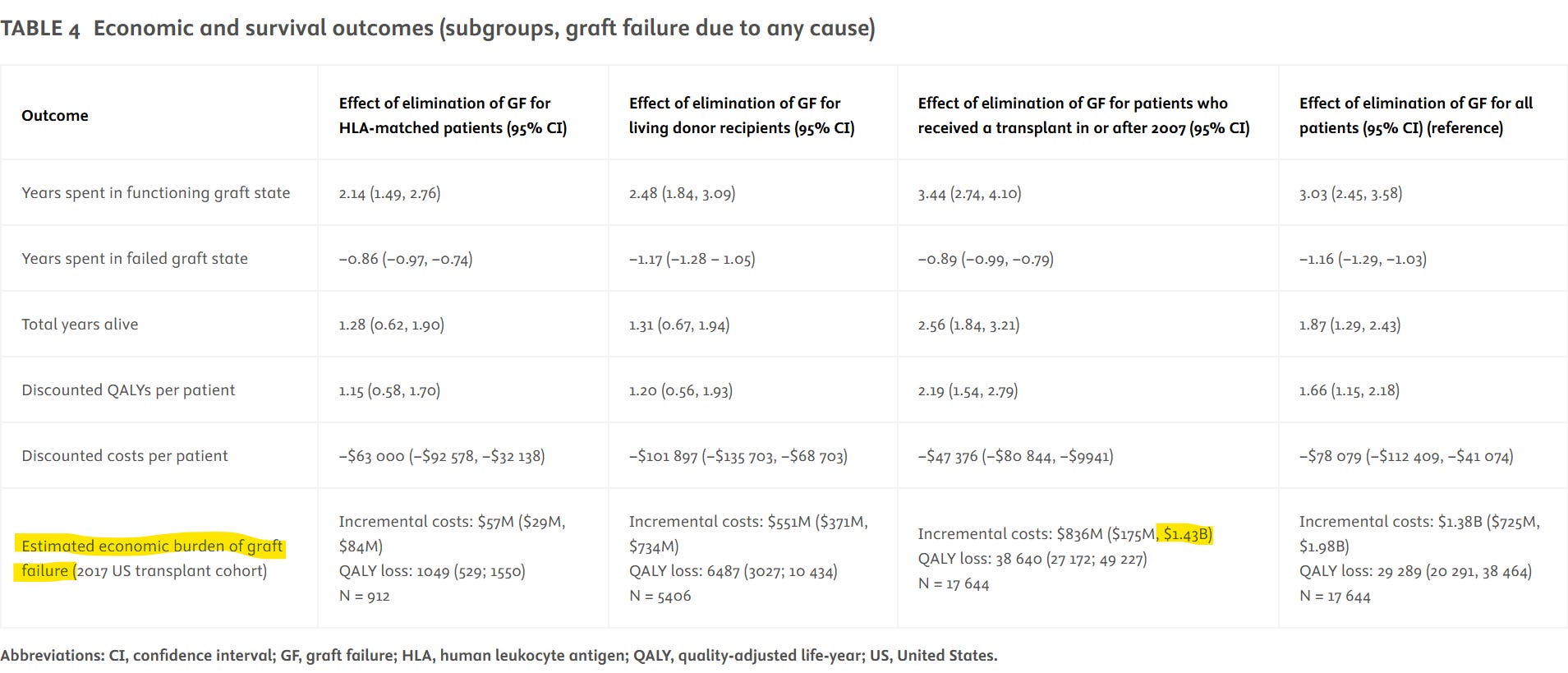

Q: You also mentioned a patient population that often gets overlooked—those with failing transplants.

BH: That’s right. There are about 250,000 people in the U.S. living with a functioning kidney transplant, and 4–5% of them lose their grafts every year. That’s a big population.8

What’s troubling is that no one is systematically responsible for their care after year one. Transplant nephrologists are focused on new transplants. General nephrologists often don’t have the training—or the bandwidth—to manage these complex patients long-term.

As a result, many of these patients crash back onto dialysis in a suboptimal way. They often start with a catheter, don’t get timely education about home therapies, and their outcomes suffer. A study in AJT by Sussell et al. estimated that avoidable spending from premature graft loss was $1.4 billion annually. That’s a huge opportunity for improvement—and for value-based care models to step in.9

Q: So if IOTA is step one—what does step two look like?

BH: I think the next step is building a comprehensive, transplant-inclusive value-based care model—one that brings together general nephrologists, transplant centers, dialysis providers, and even commercial payers.

We need a system where patients don’t get handed off between silos, but are instead followed by a coordinated team over the entire trajectory of kidney disease—from CKD to dialysis to transplant and beyond. That’s how we stop losing people in the system. That’s how we create continuity.

We haven’t done it yet. Not at scale. But the pieces are there—we just need to connect them.

Q: You laid out a model for a more integrated system, but you were clear that it was not meant to be prescriptive. What was your thinking there?

BH: I don’t believe there’s a single perfect solution to how we fix kidney care. The model I proposed wasn’t meant to be the answer—it was meant to start a conversation. It’s a framework to show what a more integrated, transplant-inclusive system could look like, not a blueprint for how we get there.

We need to harmonize systems of care—not just standardize them. A solution that works in one region may not work in another. My hope is that people take what’s useful, adapt it to their local realities, and build on it. If we share what we learn from those efforts, that’s how we make real progress.

Author’s note: For more detail, Dr. Hippen wrote this piece in December 2024, shortly after the final rule was announced.

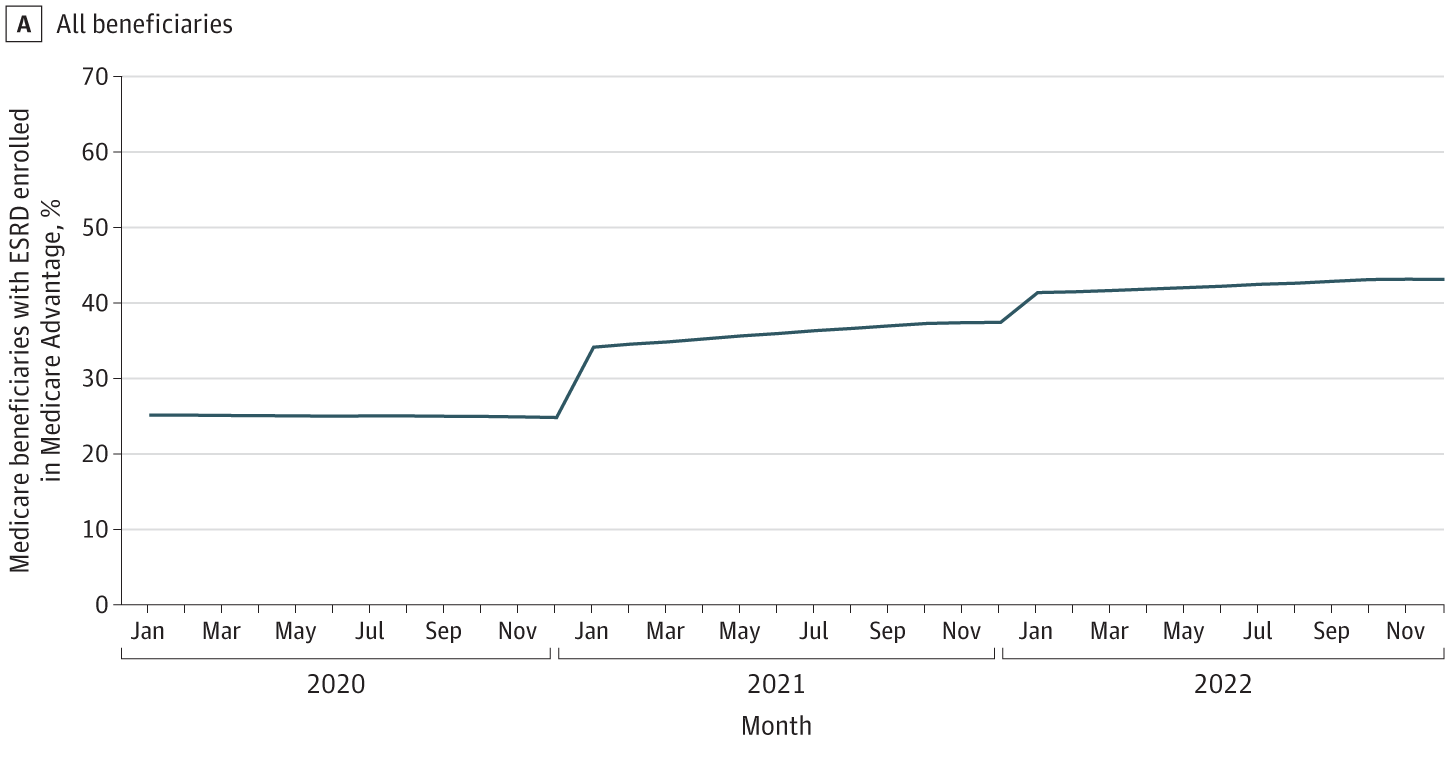

Q: You brought up Medicare Advantage as a factor that’s “quietly” reshaping the space. What are you seeing there?

BH: I’ll be honest—I didn’t see the rapid rise of MA in the ESKD population coming. But now that we’re here, it’s creating real uncertainty in how we design and scale value-based care models.

Right now, patients with MA plans are exempt from CMMI payment models. So even though their data is included in IOTA’s performance scoring, they’re not included in the financial upside or downside. That’s a big gap—especially as MA enrollment among Medicare-eligible patients approaches 50%.10

The risk is that as more patients move to MA, traditional Medicare models become less relevant, and we’ll be left with a fragmented landscape where every commercial MA plan needs a custom value-based contract. That’s incredibly complex, and most MA payers aren’t structured to handle transplant and dialysis contracting together.

So unless CMMI chooses to explicitly include MA patients in future models—or commercial payers step up—it’s going to be hard to build the kind of seamless, transplant-inclusive care models we need.

[End of Q&A]

Discussion

What will it take for us to go from "fixing the funnel" to following the full journey—especially for the 5 out of 6 patients we’re losing on the transplant path?

What’s the right balance between volume and efficiency when it comes to these efforts to standardize transplant programs, improve transparency, and shift our focus to longer-term transplant outcomes?

How do we better serve patients with failing or failed allografts, and how can we build better safety nets for this overlooked population?

How might the growing enrollment of Medicare Advantage complicate or splinter federal value-based care initiatives?

What did you think of these discussion? What other questions or comments do you have for Dr. Hippen?

Hippen BE, Hart GM, Maddux FW. A Transplant-Inclusive Value-Based Kidney Care Payment Model. Kidney Int Rep. 2024 Feb 9;9(6):1590-1600. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2024.02.004. PMID: 38899170; PMCID: PMC11184397.

Dr. Hippen on the Finalization of the Improving Organ Transplant Access (IOTA) Rule — freseniusmedicalcare.com

Medicare Program; Alternative Payment Model Updates and the Increasing Organ Transplant Access (IOTA) Model — federalregister.gov

Husain SA, King KL, Pastan S, et al. Association Between Declined Offers of Deceased Donor Kidney Allograft and Outcomes in Kidney Transplant Candidates. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e1910312. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10312

Optimizing Usage of Offer Filters: OPTN Website, Presentation, Proposal, and Comments — optn.transplant.hrsa.gov

“How will participating hospitals’ performance be measured under the model, and will they be paid?” Participating transplant hospitals receive upside risk payments from CMS; fall in a neutral zone in which the hospitals neither receive an upside risk payment nor owe a downside risk payment; or, beginning in performance year two, owe downside risk payments to CMS. The payments are based on a participating transplant hospital’s final performance score after each performance year. The final performance score is out of 100 possible points and is calculated on a set of proposed metrics in three domains: achievement, efficiency, and quality. The maximum positive payment per Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) transplant under the model (the upside risk payment) is $15,000. The maximum negative payment per Medicare FFS transplant under the model (the downside risk payment) is $2,000. — cms.gov

McPherson LJ, Walker ER, Lee YH, Gander JC, Wang Z, Reeves-Daniel AM, Browne T, Ellis MJ, Rossi AP, Pastan SO, Patzer RE; Southeastern Kidney Transplant Coalition. Dialysis Facility Profit Status and Early Steps in Kidney Transplantation in the Southeastern United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021 Jun;16(6):926-936. doi: 10.2215/CJN.17691120. Epub 2021 May 26. PMID: 34039566; PMCID: PMC8216615.

United States Renal Data System. 2024 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD, 2023.

Sussell J, Silverstein AR, Goutam P, Incerti D, Kee R, Chen CX, Batty DS Jr, Jansen JP, Kasiske BL. The economic burden of kidney graft failure in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2020 May;20(5):1323-1333. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15750. Epub 2020 Feb 4. PMID: 32020739.

Nguyen KH, Oh EG, Meyers DJ, et al. Medicare Advantage Enrollment Following the 21st Century Cures Act in Adults With End-Stage Renal Disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(9):e2432772. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.32772

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IXc-!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9f7142a0-6602-495d-ab65-0e4c98cc67d4_450x450.png)

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lBsj!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_48,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0e0f61bc-e3f5-4f03-9c6e-5ca5da1fa095_1848x352.png)