So, you want to change the world.

The art of what is possible when it comes to changing kidney policy.

This guest post is part of an ongoing series that spotlights voices across kidney care. This week’s post is by Miriam Godwin, Vice President of Health Policy and Clinical Outcomes at the National Kidney Foundation.

It takes courage and creativity to navigate our political system to advance change for people impacted by kidney disease. It starts when so many of us sit down at the start of the workday driven by an aspiration to make the United States healthcare system better for the people who rely on it. Maybe you do this through direct patient care, or by developing new drugs and innovative technologies, securing health coverage for people who need it, addressing social determinants of health, operating a health plan, writing state or federal regulations, or through thousands of other mechanisms important to different constituencies working to improve health in our country.

Systems Change - It’s Tough!

Most people agree that our healthcare system needs to change, but what does that mean and how does it happen?

An old joke is that the United States healthcare barely qualifies as a system, a system being defined as an interconnected group of entities that function for a common purpose. In the US, we have a complex so-called system of mixed financing (both public and private) on which we spend almost 20 percent of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP). For all that spending, we get fragmented processes, middling outcomes and an affordability crisis. If the common purpose is the provision of basic pillars of health to 340 million Americans, we are doing a poor job. On the other hand, there are things at which the United States excels, for example, we drive the world in research & development and the provision of tertiary care (specialized care delivered in the hospital), which people come from all over the world to benefit from. These count as health too.

Systems change through “sustained changes in policies, processes, relationships, and power structures, as well as deeply held values and norms.”1 In my role at the National Kidney Foundation, I work to achieve system change for kidney patients through political tools like laws and regulation. U.S. healthcare is intimately entwined with politics because we – yes, you if you’re a U.S. taxpayer – finance it at a cost of at least $1.8 trillion, or about 40% of our country’s total health expenditures of $4.5 trillion.2 In addition, we foot the bill for insurance premiums and deductibles, and out of pocket expenses like copays and coinsurance, and healthcare services that aren’t covered by insurance at all. Healthcare now consumes nearly 20 percent of the U.S.’ GDP, a fact that keeps politicians and policymakers of every party awake at night with heartburn.3

It doesn’t take long working on issues in kidney care to hear “those people in government don’t know what they’re talking about.” My response would be – is that true or does our political system require policymakers to deal with an exceedingly difficult set of constraints? The magnitude of healthcare financed by the taxpayer means there is no so-called free money to pay for hospitals, physician and clinician services, pharmaceuticals, and other products and services our system provides. As a result, how we pay for healthcare is too often a function of paying more for one thing and less for another. If we want more money for health, we must agree as a country to pay for it. Recall also that when Congress writes laws that grant new authorities to agencies, those authorities are limited by the law. Passing laws at all, meanwhile, is as difficult as it has ever been in American history. Lastly, most systems, including our healthcare system, are a mix of elements that are working for some people and elements that are not working for others. The laws of the land, taxation, and the reshuffling of systems to accord with the values of different groups of Americans are three big political challenges.

How Does Change Happen?

This is the part where I explain the art of the possible. We’ve covered some of the limitations of our political system that make changing our healthcare system particularly difficult. There is hope, too. Should we really wish to use politics to improve kidney care for the people we serve, we can. It won’t be easy, but it can be done.

In our political system and especially these days, transformation doesn’t happen with the snap of the fingers. New laws don't pass that magically overcome financial and political constraints. Rather, it is incumbent on all of us who wake up wishing for a better world for people affected by kidney disease to do the sometimes tedious, sometimes invigorating, incremental work of advancing where and how kidney care is delivered, by working with policymakers working for state and federal government.

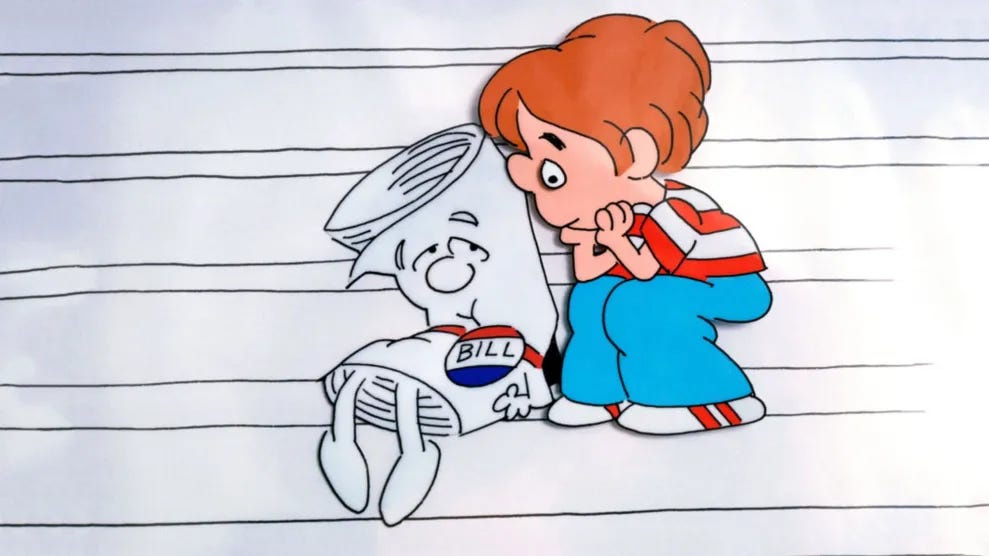

Thanks to the ubiquity of Schoolhouse Rock over forty years in the cultural milieu, many people know the basic story of how a bill becomes a law. Once the President signs a bill into law, the President and the Executive Branch are responsible for implementing the laws written by Congress. In a simple rubric, the implementation of a law is where a public policy lives or dies, works or not, changes the context in which healthcare is delivered, and touches a human person in a vulnerable moment in their life.

I get it – aside from a few big-time nerds, me included, not many people in the “kidneyverse” want to spend the July 4th weekend reading the five-hundred-page ESRD prospective payment system regulation written in inscrutable legalese. While that perspective is understandable, I would argue for paying attention to what’s in it since the ESRD payment system governs issues of enormous importance to patients and families. For example, the ESRD payment system helps rural facilities keep their doors open, determines whether dialysis patients are screened for depression and receiving adequate dialysis, and – even if you vigorously disagree about how the government defines it – sets the process for adopting new dialysis technology. These are just three examples, and the ESRD prospective payment system interacts with many other issues that touch the day to day lives of people who rely on dialysis to live.4

Holding on to Aspiration

Working in health policy will turn almost anyone into a pragmatist, but I believe in holding space for the aspirational as well: what could we do in kidney if anything were possible?

The work of changing kidney care for the people who need it is enormously difficult, time consuming and laborious, and it is also desperately needed. It requires us to hold both the practical – what can I do today – our ambitions and hope that one day we can do so much more – and our sadness and regret when health coverage we have worked so hard to secure for kidney patients threatens to erode.

No, you don’t have to change the world by reading federal regulations (your friends in the professional society that represents you have you covered there) but it is incumbent upon all of us to tolerate working in the political system we have today, with all its limits and frustrations, to create new opportunities and drive solutions. Kidney patients need us to lean into complexity to find the levers that will change their lives, while working towards an environment of greater possibility, of vision and the dream we share of eliminating kidney disease.

The practical and aspirational are political projects, the tensions that have pushed and pulled at American governance for 250 years. Changing anything starts with ideas and happens through determination and grit. We have plenty of that in the kidneyverse so let’s get going to change the world. Our patients need us.

Discussion

We hope you enjoyed this week’s post and topic. What are your thoughts? Share your comments, experiences, and questions with us in the comments below.

Potential: Where do you see untapped potential in kidney health if anything were possible? What reforms or innovations would you pursue if constraints were lifted?

Examples: Have you seen a recent policy, regulation, or pilot program that gives you hope? Share examples of where you've seen “the art of the possible” in action.

Advice: What advice would you give someone trying to make a difference today? Whether you're new or deeply involved—what keeps you going?

Measuring Systems Change: A Brief Guide (ACL.gov)

https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/what-does-the-federal-government-spend-on-health-care/

https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/health-spending-u-s-compare-countries/

https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2025-07-02/pdf/2025-12368.pdf

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IXc-!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9f7142a0-6602-495d-ab65-0e4c98cc67d4_450x450.png)

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lBsj!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_48,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0e0f61bc-e3f5-4f03-9c6e-5ca5da1fa095_1848x352.png)

Tim, this resonated big time! As big of a mountain as it appears, one call, one patient review at a time; There is an opportunity to make an impact with every single outreach.