Wanted: Kidney Care Navigators

Cancer care made navigation standard. Is kidney care next?

Patient navigation works. It’s not just a theory—it’s standard practice in oncology. Recent reimbursement changes mean more patients with serious and complex illnesses will now have access to these services, with CMS formally recognizing their value through new billing codes. Yet in kidney care? It seems we’re still trying to find the map. In last week’s Signals poll, I asked what’s holding kidney care back from scaling similar patient navigation services. The top response: cost and reimbursement (44%), followed by the challenge of coordinating across multiple care settings (35%) and provider buy-in (17%).

Those results track with what we’ve heard in the field. I chose these three barriers based on what I’d seen and heard often over the years while implementing a novel home dialysis patient education solution. But cost isn’t the only issue, and as much as kidney and cancer care have in common from a patient journey standpoint, comparisons start to fall apart when we look at our underlying kidney care infrastructure (see below).1

What we heard in comments and direct messages painted a far more complex picture. That is what we’re going to unpack below, alongside promising signs of change and examples of how we’ll get there.

A Tale of Two Systems

Navigation programs exist to help patients find their way through the healthcare system. In cancer care, that means making sure no one gets lost between diagnosis and treatment, or left behind in the follow-up process. Navigators help patients schedule appointments, manage insurance issues, communicate across specialties, and access psychosocial support. They’ve become essential in oncology, where the journey is long, nonlinear, and emotionally complex (sound familiar?). CMS recently formalized its value by reimbursing Principal Illness Navigation (PIN) services for cancer patients starting in 2024.23

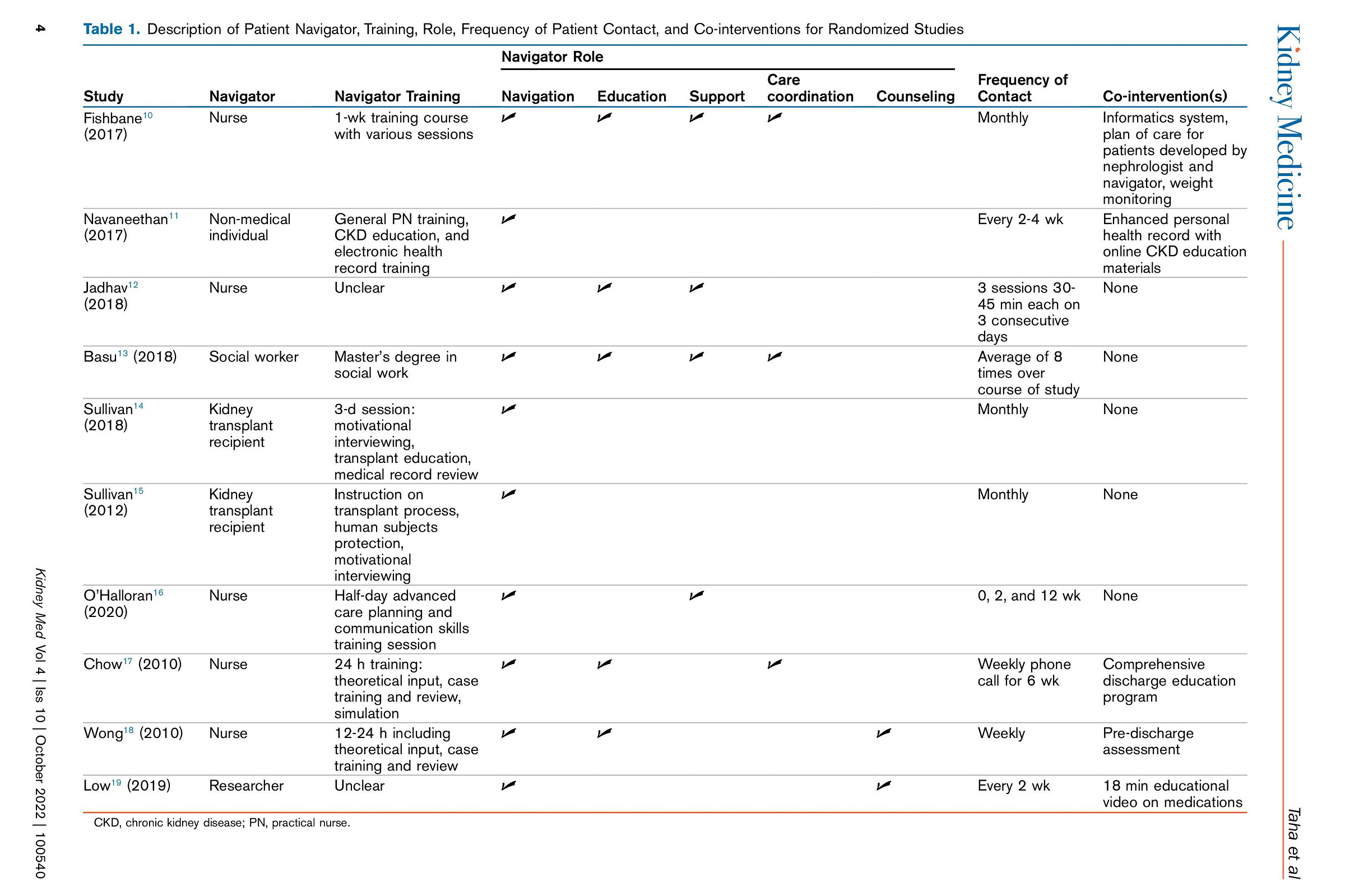

Kidney care patients face many of the same challenges—but with far less support. That’s what makes a recent systematic review in Kidney Medicine so relevant. Researchers examined 17 studies evaluating navigation programs in CKD and kidney failure (see table below). While most showed some positive outcomes—like improved transplant workup, greater peritoneal dialysis use, and better patient knowledge—there were notable limitations. Few studies looked at cost-effectiveness or patient-reported experiences. And many had high risk of bias or unclear standards for what a “navigator” actually does.

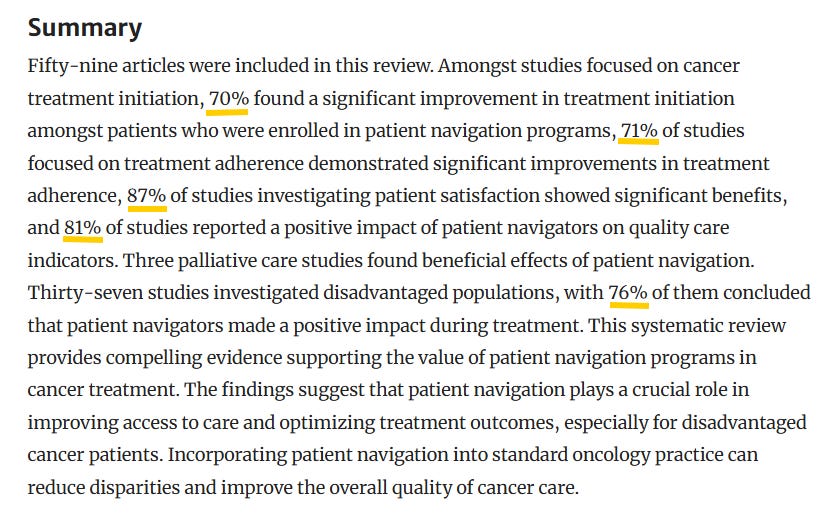

Compare these with oncology. The above review in Current Oncology Reports found that navigation programs led to measurable improvements in treatment initiation, adherence, patient satisfaction, and quality of care. Navigation is now considered a standard part of cancer treatment—especially for high-risk or underserved populations. In kidney care, we’re still figuring out who should lead, what success looks like, even though we already know how to pay for it (more on that later).

The Kidney Care “Journey”

It might help to rethink how we imagine the patient journey in kidney care. Unlike most stories with a clear beginning, middle, and end, this one is not a straight line. In fact, what you find is often many lines reaching in different directions, changing course at every turn. Sadly, there is no narrator either. Several patients and clinicians shared firsthand insights that paint a more complex picture.

One patient advocate noted the dizzying coordination required between PCPs, nephrologists, dialysis, transplant, and other care teams—and emphasized that many organizations lack proper training programs for patient navigators, making it difficult to scale the model. A nephrology nurse pointed out that CKD patients often see multiple specialists with no clear care "quarterback." A clinician underscored how patients must navigate dialysis education, transplant referrals, vascular access, home readiness assessments, and more—all while managing comorbidities and a regular dialysis regimen. A policy expert added that, unlike oncology, kidney care lacks a unified patient pathway and has no agreed-upon standard for who should lead care coordination.

In this landscape, patient navigation isn’t just a support service. It’s connective tissue. It’s someone who knows the map. As one nurse put it: “We have enough intelligent people and resources to build a care map from a healthy patient to Stage 5 — why haven’t we?”

What’s Working

While many providers cite lack of reimbursement as a barrier, others are already proving that navigation works in kidney care — especially when embedded within risk-bearing models. (Yes, you read that right.) Let’s begin with an example of Medicare Advantage, full-risk, primary care-led healthcare delivery that integrates specialist recommendations into a patient’s care plan.

ChenMed, a primary care organization operating under a full-risk model, has built a nurse navigation program specifically for ESRD and late-stage CKD. These “Chen K” nurses come from dialysis backgrounds and act as a bridge between nephrology and primary care. One nurse described their role as part educator, part advocate, part logistics coordinator—troubleshooting issues like fluid management, vascular access, or medication adherence while making sure patients are informed and engaged in their decisions.

Virginia Irwin-Scott, DO, who leads the program nationally, explains that alignment across care teams is key. “If your primary care doctor is speaking the same language as the nephrologist, as the endocrinologist, as the cardiologist, you get better buy-in from the patient,” she said. “As in, ‘let’s control your diabetes, let’s do a low salt diet, let’s watch your fluid intake. How is your weight doing? What is your blood pressure?’” The company’s model gives providers flexibility to address social determinants of health, coordinate transplant referrals, and introduce home dialysis options earlier in the care journey.

Two time zones and roughly two thousands miles west, a similar story has been unfolding at Intermountain Health since 2019. Their nurse navigators work within a large integrated system to support early identification and care planning. In 2025, 76.5% of Intermountain patients started dialysis optimally, with nearly half receiving pre-emptive transplants. Among patients covered by SelectHealth, the system’s own insurance plan, the results were even stronger. According to program leaders, 100% of those patients had optimal dialysis starts and 67% began with a pre-emptive transplant.

Seth Southwick, who helps lead Intermountain’s Kidney Services efforts, recently told AJMC that these outcomes are driven by data analytics and machine learning models that flag high-risk patients early. The team then uses that information to prioritize outreach and connect patients with the resources they need—before complications arise. I’d say from the sounds of it they’re doing a lot of things right, so I’m excited to have the teams from Intermountain and ChenMed on to talk about their work in an upcoming conversation in our ongoing KOLs series.

These two examples—spanning different regions, populations, and models—show what’s possible when navigation is built into the infrastructure and longitudinal patient journey from the start.

Outcomes May Vary

Not all studies show clear or immediate benefits. Two randomized controlled trials from the transplant world help illustrate why. In a trial across 40 dialysis units in Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky, Sullivan et al. tested whether trained kidney transplant recipients could help other patients move through the transplant process. After a year, there were no significant differences in transplant referrals, waitlisting, or transplants received between those with a navigator and those without.

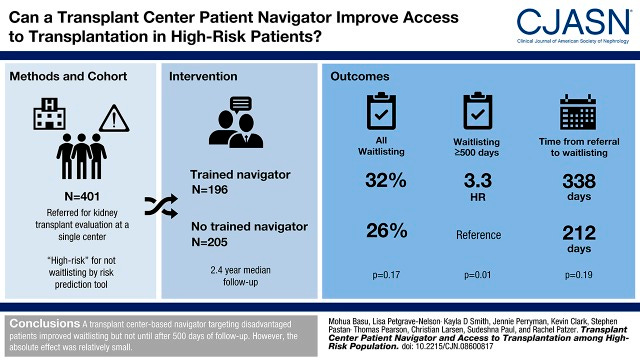

But another study by Basu et al. at a single transplant center told a different story. Here, a center-based navigator targeted patients at high risk of dropping out of the evaluation process. Early on, the intervention had no measurable impact. But after 500 days, patients with a navigator were more than three times as likely to get waitlisted. The absolute effect was modest, but it highlighted something important: navigation’s value may take time to materialize—especially in complex, high-barrier populations.4

Together, these studies suggest that the effectiveness of navigation depends heavily on timing, context, and the specific barriers being addressed—not just the presence of a navigator alone.

The Next Chapter

With new CMS reimbursement codes for Principal Illness Navigation (PIN) services, navigation isn’t just for oncology anymore. PIN codes (G0023/G0024) can now be billed for patients with serious, high-risk conditions lasting three months or more. As Amber Paulus points out, that includes many people with Stage 3 to 5 CKD. That means navigation services for these patients can now include support for medication adherence, lab work, lifestyle change, dialysis preparation, and transplant referral. For organizations operating in value-based care models, this is a powerful new tool—if they choose to use it.

But payment alone won’t be enough. The conversation is also about leadership, clarity, and thoughtful design. Kidney care needs clear ownership of the patient journey—whether that falls to health systems, primary care, nephrologists, or other specialists. It needs standardized training, better integration with existing care teams, and culturally competent models that recognize the specific needs of Black, Hispanic, Indigenous, rural, and low-income communities. Navigators must know who they work for and what success looks like in a system where no shared pipeline yet exists. And most importantly, navigation efforts need to start earlier—at CKD Stage 2 or 3—when the opportunity to slow progression and build trust is greatest. These questions remain unanswered, but they’re being asked louder than ever.

What’s Stopping Us?

We now have evidence that navigation improves outcomes. We have real-world examples showing that it can work in kidney care. And we finally have new reimbursement codes that remove one of the biggest historical barriers. So the question isn’t whether navigation belongs in kidney care. The question is: what’s stopping us from building it?

If you’re running, piloting, or funding a navigation program in kidney care, we want to hear from you. And if you’re not yet, but curious where to begin, we hope this was a useful starting point. What do you want to know or learn from the community?

Thanks to all who contributed to the original poll and conversation. Your insights made this piece possible. We will continue this conversation in our ongoing interview series and in our Slack channel. Please continue sharing your stories and lessons, we’d love to hear from you.

My goal here is to show that kidney care has its own unique set of challenges, clinically, systemically, and otherwise. Cancer and kidney disease have something in common: there is no cure. And while often viewed as such, kidney transplantation is a treatment option— one that requires lifelong immuno-suppression, follow-up, and emotional and social support. Like cancer survivorship, post-transplant life involves managing uncertainty, side effects, and the risk of treatment failure. Many patients will eventually require another transplant or return to dialysis.

Chen, M., Wu, V.S., Falk, D. et al. Patient Navigation in Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review. Curr Oncol Rep 26, 504–537 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-024-01514-9

What are Principal Illness Navigation (PIN) Services? The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) began reimbursing for Principal Illness Navigation (PIN) services on January 1, 2024. PIN services are navigation services provided by auxiliary personnel or peer support specialists for Traditional Medicare patients with a serious, high-risk condition or illness. PIN services help patients navigate treatment for their health condition, including any unmet social needs (Rural Health Information Hub).

Sullivan CM, Barnswell KV, Greenway K, Kamps CM, Wilson D, Albert JM, Dolata J, Huml A, Pencak JA, Ducker JT, Gedaly R, Jones CM, Pesavento T, Sehgal AR. Impact of Navigators on First Visit to a Transplant Center, Waitlisting, and Kidney Transplantation: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018 Oct 8;13(10):1550-1555. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03100318. Epub 2018 Aug 22. PMID: 30135171; PMCID: PMC6218827.

Basu M, Petgrave-Nelson L, Smith KD, Perryman JP, Clark K, Pastan SO, Pearson TC, Larsen CP, Paul S, Patzer RE. Transplant Center Patient Navigator and Access to Transplantation among High-Risk Population: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018 Apr 6;13(4):620-627. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08600817. Epub 2018 Mar 26. PMID: 29581107; PMCID: PMC5968906.

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IXc-!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9f7142a0-6602-495d-ab65-0e4c98cc67d4_450x450.png)

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lBsj!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_48,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0e0f61bc-e3f5-4f03-9c6e-5ca5da1fa095_1848x352.png)

Another great analysis, Tim! A few thoughts:

1. Further leaning into the point about risk stratifying the population until, in the words of Tina Fey, "everybody hates it:" G3a CKD with A1 albuminuria is a very different patient from one with G3a CKD and A3 albuminuria. Every specialty is going to have their own model for dealing with CKD/CKM (PCP, NKF's CKDintercept, American Heart Association will claim cardiology, etc.). We will get better (hopefully) at identifying where patients are best managed, whether PCP or specialty care, and that will inform the ROI on care navigation from policy, operations, and health system standpoints and help us deal with that old chesnut of heterogeneity in the CKD population, which is so endlessly maddening to the good folks paying for all of this.

2. As usual (and why does he really need any help?) the devil is in the details on the PIN codes. It is great to have them and incident-to billing is an operational challenge, to say the least, and that is subject to the same opportunity cost as we see with KDE of, "is this really worth my time?" That would be the argument for the ChenMed model of working with care navigation through a total cost of care model where optimally, navigation and faciliation become part of the care model. On the other hand, having a traditional fee-for-service model makes it much easier to try out PIN and see what works, especially with a mixed short-term ROI. So, as with most things, chicken or egg, etc.

3. I think there are many opportunities to improve care navigation with community health workers, particularly in settings where cultural concordance is very important (like dialysis). There, the reimbursement issues are more concrete but also more solvable. For example, the nephrologist billing the MCP can initiate services and then a CHW can step in and be paid. Similarly, an ESRD Network can hypothetically initiate services, but it would have to be under an NPI, etc.

I personally have not but would be interested to see who is using them in CKD. I think there is definitely an opportunity to utilize them in at least advanced CKD (stage 5) and those with CHF and CKD.