Winner Take All: Does Transitional Care Billing Undermine Team-Based Kidney Care?

How “first past the post” billing rules make it harder to deliver coordinated care for patients with complex needs.

This piece is part of a new series on Signals spotlighting frontline voices across kidney care. This week’s guest post is by Dr. Katie Kwon, a private practice nephrologist in St. Joseph, MI, and Vice President of Clinical Affairs with Panoramic Health. She serves on the board of the Renal Physicians Association.

Transitional care management (TCM) visits are structured outpatient visits, designed with the goal of compensating providers for the complex care coordination needed after a hospital discharge. Readmissions within thirty days of discharge cost the US healthcare system approximately $52.4 billion dollars annually.1 TCM visits are meant to help prevent avoidable readmissions. However, CMS currently limits reimbursement for a TCM visit to the first provider to file the code within the post-discharge window. Our current health system is fragmented, and complex patients require multidisciplinary care. Offering a high-value code in a “first past the post” reimbursement format is contrary to the goal of fostering coordinated, holistic care.

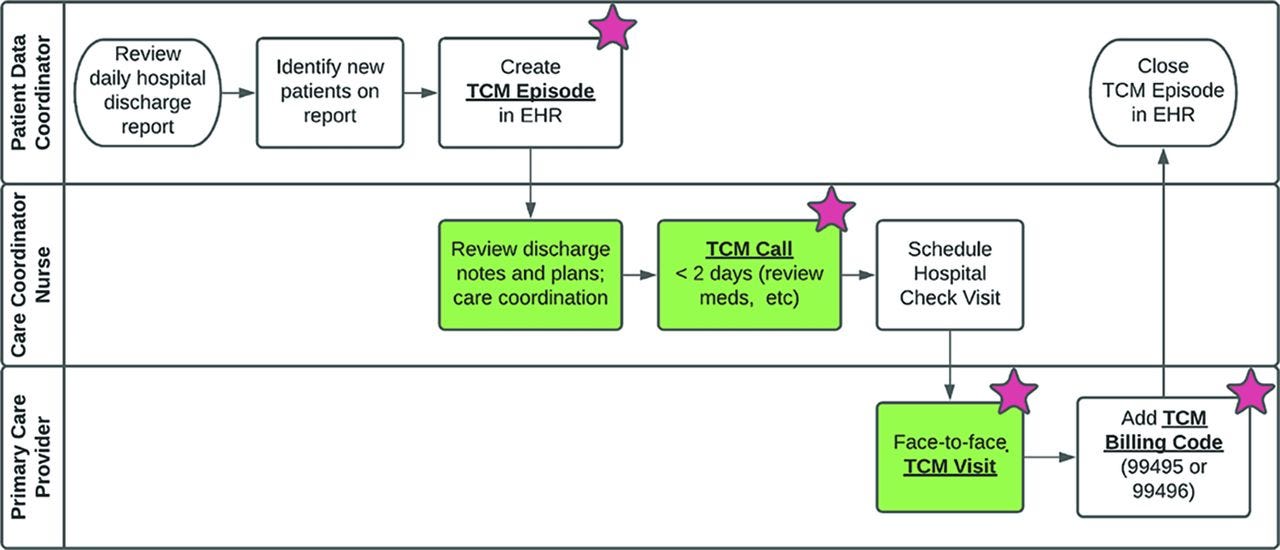

TCM visits (CPT codes 99495 and 99496) have required elements, including early phone contact from the office, medication reconciliation, and review and follow-up of hospital records and any pending tests or treatments. Visits must take place within seven to fourteen business days of discharge. While a regular level four office visit (CPT code 99214) has a total assigned relative value unit (RVU) of 1.8, the RVUs for TCM visits are significantly higher. For an independent practice that doesn’t receive a facility fee, the RVUs are 3.27 and 4.40 respectively.2 This reflects the additional work created by a fragmented healthcare system, as accessing information from the hospital can be challenging when the billing practice uses a different electronic health record (EHR.)

Multiple structural investments are required in an outpatient chronic kidney disease clinic (CKD) to enable getting patients scheduled within the seven day window. Office staff need to know which patients are hospitalized and when they are discharged. They need time to make calls within 48 hours of discharge, and training in what to ask and how to chart it. Clinic schedules need to have spaces held open to allow scheduling within the required timeframe. These visits can be lengthy and do not lend themselves to overbooking. During the visit, discharge records must be available for review by the clinician, so they have to be obtained in advance.

We had a recent inpatient consultation on a very common patient scenario – a gentleman with cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome who was admitted with decompensated heart failure and acute kidney injury (AKI). We were involved in managing his diuretics and the rest of his medications used to treat his underlying CKM syndrome. Patients with these comorbid conditions are at high risk of readmission. At discharge, he was not yet euvolemic, and certain elements of his CKM therapy remained on hold, awaiting resolution of his AKI and successful decongestion.3 Reestablishing therapies such as sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors quickly are critically important to preventing recurrent decompensation.

Such patients are well positioned to benefit from TCM visits, which provide early and comprehensive follow-up. We scheduled the patient to be seen five days after discharge. However, when he arrived for his appointment, a review of the EHR showed that he had had a TCM visit with his primary care doctor the day before. The required TCM elements were present, and the PCP had noted that the SGLT2i remained on hold. Under “plan” for his heart failure, the PCP had written “follow up with nephrology regarding reinitiation of SGLT2i.”

It's debatable whether this rises to the required level of medical decision making for the PCP to bill a TCM visit. However, the charge had been filed, so it was clear that we would not be compensated for the work we had already done. We saw the patient, restarted his indicated SGLT2i to reduce his risk of HF decompensation, and billed a level four follow-up visit with a much lower RVU. The important outcome, of course, is that the patient was placed on his needed medication regimen. The larger systemic problem, however, is that our office is less likely to invest the extra work to provide TCM visits if we lose out on the opportunity to bill for them.

Uptake of therapies for cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome remains low. In one recent analysis, less than 30% of patients discharged with HF with an EF > 40% received an SGLT2i at discharge, and rates were even lower in patients with kidney failure.4 Rates also varied widely across hospitals, likely reflecting the importance of local experts who have developed confidence in these relatively new therapies. This highlights the importance of interdisciplinary care. The “first past the post” compensation rules around TCM visits could lead to providers defaulting to later follow-up visits, since they risk losing compensation for the extra work TCM visits require. This is a disservice to medically complex patients that need input from multiple specialists.

Discussion

We hope you enjoyed this week’s post and topic. What are your thoughts? Share your comments, experiences, and questions with us in the comments below.

How do you currently handle post-discharge follow-up for complex CKD patients? What’s working—and how are you leveraging TCM visits?

Have you encountered issues with the “first-to-bill” TCM structure in your own practice? How confident are you that you'll see the denials for TCM visits because someone else did one first?

How can PCPs and nephrologists work together to ensure CKD patients don’t fall through the cracks after hospitalization? Are there handoff practices, EHR flags, or shared care practices that have worked?

Beauvais B, Whitaker Z, Kim F, Anderson B. Is the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program Associated with Reduced Hospital Readmissions? J Multidiscip Healthc. 2022 May 12;15:1089-1099.

Nuckols T, Keeler E, Morton S, et al. Economic Evaluation of Quality Improvement Interventions Designed to Prevent Hospital Readmission: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):975–985. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1136

https://cpt-international.ama-assn.org/relative-value-units

https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/japplphysiol.00165.2019

Abdel Jawad M, Spertus JA, Ikeaba U, Greene SJ, Fonarow GC, Chiswell K, Chan PS. Early Adoption of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitor in Patients Hospitalized With Heart Failure With Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2025 Jan 1;10(1):89-94. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2024.4489. PMID: 39556474; PMCID: PMC11574726.

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IXc-!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9f7142a0-6602-495d-ab65-0e4c98cc67d4_450x450.png)

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lBsj!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_48,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0e0f61bc-e3f5-4f03-9c6e-5ca5da1fa095_1848x352.png)