Hidden Costs: The Care We Fail to Count

A patient and caregiver’s letter on what the system asks but never measures

This guest post is part of our ongoing series highlighting voices from across kidney care. Today we’re sharing a piece by Jeff Parke, a 30-year dialysis patient, multi-kidney transplant recipient, and advocate for structural reform in dialysis and organ transplantation.

No one ever asked how much of myself I could give before I disappeared.

When transplant became the plan, it was as if the room silently agreed that “care” would be there, on demand, without limit. It was treated like gravity: assumed, invisible, powerful enough to hold everything on solid ground. The charts listed my labs and my medications. They never listed the hours my partner spent on hold with insurance, the miles driven before dawn, or the number of nights one of us lay awake, listening for a sound that meant something was wrong.

From the patient side, transplant is a strange kind of second birth: you wake up in a body that has been opened and repaired, but nothing around you feels familiar. You are suddenly dependent on routines that did not exist before—timed pills, forbidden foods, temperature checks, infection rules. The world shrinks to numbers on a screen and instructions taped to the fridge. You feel both grateful and trapped. Philosophers call this a “liminal” state: no longer who you were, not yet someone who feels whole. Life becomes a hallway you aren’t sure you ever get to leave.

In that hallway, love slowly turns into labor.

Life after transplant

Our days were carved into small, precise pieces. Alarms dictated when I swallowed one pill and waited for another. The kitchen counter became a landscape of bottles and boxes. The calendar began to look less like a month and more like a puzzle: lab days, clinic days, refill deadlines, all fitted together around the hope that something resembling normal life could still exist in the cracks. The house looked quiet from the outside. Inside, it felt like a control room.

Psychologically, we were running two operating systems at once. One tried to process what had happened: the violence of surgery, the miracle of a working organ, the guilt of knowing that my survival was tied to someone else’s loss and my partner’s constant watching. The other tried to keep the machine running: Did we order the refills? Did we write down the new dose? Did we reschedule that appointment we had to move? It is hard to feel like a person when your mind is permanently in “task manager” mode.

Care is often described as compassion, but what it felt like, most days, was project management with a beating heart at the center.

What we know about caregiver burden

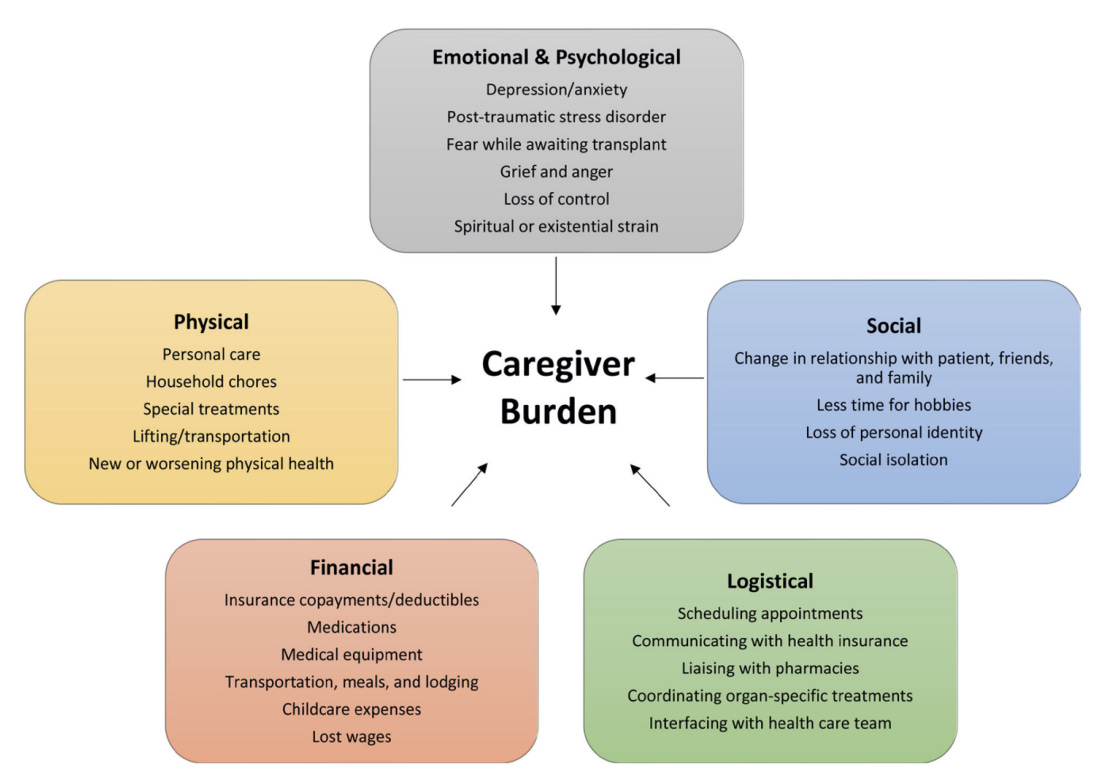

The psychology of this is not a mystery. Long before my surgery, studies were already describing “caregiver burden” in transplant: the way spouses and family members develop anxiety, depression, sleep problems, and health issues of their own under constant strain.1 Reviews of caregivers across solid organ transplant find the same patterns: chronic hyper‑vigilance, feeling “always on,” and little time or space to process what any of it means.2 None of this was news to us, because we were living the footnotes.

Figure: Domains of Caregiver Burden

What the research calls “burden,” I would describe as an erosion of boundaries. There was no clear line between where my illness ended and my partner’s life began. My fear leaked into her sleep. Her exhaustion leaked into my guilt. Our shared future was being rewritten by lab slips and appointment times, but the system spoke to us as if we were two separate entries: patient, caregiver. It did not account for the way our minds and nervous systems were braided together.

That is the existential toll: feeling your own life narrowing down to survival tasks, while watching someone you love lose pieces of themselves in the process.

What we fail to measure

And still, in many conversations, transplant success is mostly translated into numbers: one‑year graft survival, hospitalization rates, cost curves.3 The new narrative some are calling for—one that centers what life actually feels like after kidney transplant—rarely makes it into how success is measured and valued. As Kevin Fowler writes:

…A [post-transplant] pilot model that offers physical rehabilitation, psychological counseling, mentorship, etc. would be a step forward in validating the patient experience while aligning with national policy… The full value of a kidney transplant will not be achieved without rehabilitation support. It is analogous to buying an expensive automobile without routine service.4

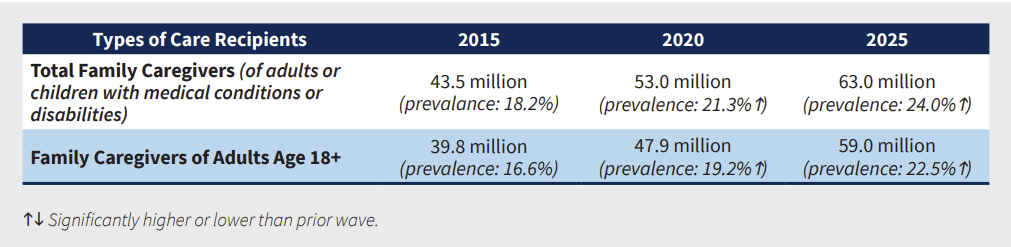

Table: Est. Number of Family Caregivers, 2015-2025

Unpaid caregiving is one of the biggest hidden subsidies in this system. A 2025 report from AARP estimates that family caregivers in the United States provide roughly $600 billion dollars’ worth of unpaid care each year—more than the total annual spending on Medicaid. A separate analysis from Otsuka and the National Alliance for Caregiving puts that figure even higher, at nearly $874 billion dollars in unpaid labor. Those costs are felt by bodies like ours: backs that hurt, nerves that fray, savings that drain, jobs that bend or break under the weight of “just helping.”

But on paper, that labor is free. In fancy dashboards, it doesn’t get counted.

Given what we know about the mental and physical toll of caregiving, it is not hard to imagine how sustained strain could ripple outward. Missed medications, delayed follow-ups, or preventable hospitalizations can emerge long before anyone recognizes there’s a problem. Yet most transplant centers still lack structured support for caregivers, with no routine way to ask, “How much do you have left?” before something gives.5 It is as if we designed a state-of-the-art bridge, watched the support beams crack, then blamed gravity.

For us, care felt less like a gentle virtue and more like a bank account we were never allowed to replenish. Every appointment, every 3 a.m. check, every argument with insurance was a withdrawal. The “deposits” were rare: a friend who offered a ride without being asked, a clinician who actually paused and asked my partner how she was coping, a day when nothing urgent happened and we could remember what it felt like to laugh about something unrelated to kidneys. Over time, the balance dropped. We still showed up. We still said, “We’re managing.” But the margin for error got thinner and thinner.

The psychological tools we had, coping strategies, humor, and compartmentalization, started to feel like worn-out instruments. We could still use them, but not forever. Resilience is often described as bouncing back. That metaphor fails here. Sometimes resilience is just the ability to keep walking with a cracked foundation because there is no place to sit down. Eventually, the crack spreads.

This is where metaphors do better than metrics: our life after transplant felt like pushing a loaded cart with three wheels across a long, uneven road. Medicine gave us the cart and one very good wheel—the new organ. It did not account for the missing wheel, the broken one, or the people straining behind the handle.

Systems that care by design

So, what would it mean to take care seriously as a finite resource?

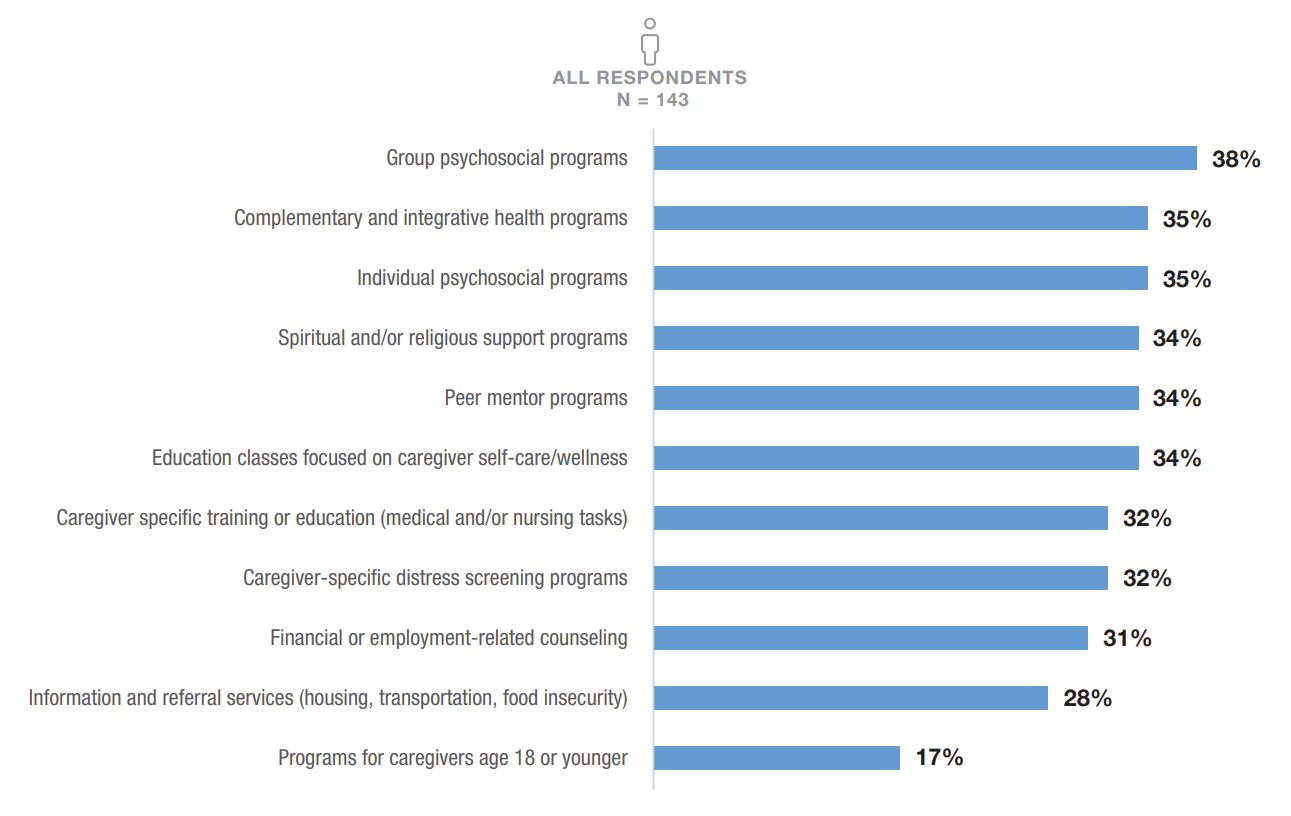

It would mean that when transplant teams talk about “access” and “equity,” they include the capacity of real households, not just the availability of OR time. It would mean caregiver training that isn’t rushed through in a single discharge session, but revisited and reinforced over time. It would mean routine mental‑health check‑ins for both patients and partners as part of standard follow‑up, not as an emergency add‑on.6 It would mean that payers and policymakers stop pretending unpaid care is free and start building respite, paid leave, and community‑based support into what “value” actually means.

And it would mean listening differently—to stories like ours, and to the patterns that show up when you put those stories side by side.

Figure: Types of Support Programs Offered By Transplant Centers

A 2018 systematic review titled “Who Cares?” describes caregivers who report feeling “taken for granted,” “constantly on duty,” and “guilty for wanting time for themselves.”7 Those phrases could have been pulled from our kitchen table. They are not isolated sentiments. They are the emotional signatures of a system that consumes more care than it ever admits.

Care is what keeps patients like me alive. That is the hopeful truth. And yet, unsupported care wears down the very people who make our survival possible. This is the part of our current system of care that we have not yet learned to count.

This isn’t a problem of individual willpower, resources, or family values. It is a design problem. We built transplant pathways that assume an endless human safety net and then look away when that net starts to fray. If we are brave enough to name that, we can be brave enough to change it, shifting from a model that silently spends caregivers’ lives to one that treats their wellbeing as central to the work of keeping people like me here, not as a footnote to a “successful” surgery.

We’d love to hear from you. Leave a comment if this essay resonated or share this story with a friend or colleague. How can we improve post-transplant care?

From the Editor

My thanks to Jeff for sharing his voice with all of us. Our most recent guest posts featured Jeanmarie Ferguson on finding her voice in the New York Times, and Dr. Karin Hehenberger on why organ transplantation still lags behind oncology in innovation and public awareness. If you want to explore more on these themes, you might enjoy our recent pieces on life on immunosuppression, the iBox score, and Michelle Yeboah’s transplant journey. Thank you for being here with us.

Deng LX, Sharma A, Gedallovich SM, Tandon P, Hansen L, Lai JC. Caregiver Burden in Adult Solid Organ Transplantation. Transplantation. 2023 Jul 1;107(7):1482-1491. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000004477. Epub 2023 Jun 20.

Jesse MT, Hansen B, Bruschwein H, Chen G, Nonterah C, Peipert JD, Dew MA, Thomas C, Ortega AD, Balliet W, Ladin K, Lerret S, Yaldo A, Coco T, Mallea J. Findings and recommendations from the organ transplant caregiver initiative: Moving clinical care and research forward. Am J Transplant. 2021 Mar;21(3):950-957. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16315. Epub 2020 Oct 9. PMID: 32946643.

Glaze JA, Brooten D, Youngblut JA, Hannan J, Page T. The Lived Experiences of Caregivers of Lung Transplant Recipients. Prog Transplant. 2021 Dec;31(4):299-304. doi: 10.1177/15269248211046034. Epub 2021 Oct 27. PMID: 34704858.

Sankar K, Johnson A, McRae K, Rampolla R, Kolaitis NA. Caregiver burden in lung transplantation: A review. JHLT Open. 2025 Mar 4;8:100239. doi: 10.1016/j.jhlto.2025.100239. PMID: 40486116.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Committee on A Fairer and More Equitable, Cost-Effective, and Transparent System of Donor Organ Procurement, Allocation, and Distribution; Hackmann M, English RA, Kizer KW, editors. Realizing the Promise of Equity in the Organ Transplantation System. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2022 Feb 25. 7, Measuring and Improving System Performance. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK580033/

Fowler KJ. Life After Kidney Transplantation: The Time for a New Narrative. Transpl Int. 2025 May 12;38:14074. doi: 10.3389/ti.2025.14074. PMID: 40421389; PMCID: PMC12104084.

https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/NAC_TransplantGapsReport_FINAL_11.05.2024.pdf

Yang F-C, Chen H-M, Huang C-M, Hsieh P-L, Wang S-S, Chen C-M. The Difficulties and Needs of Organ Transplant Recipients during Postoperative Care at Home: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(16):5798. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165798

Noonan MC, Wingham J, Taylor RS. 'Who Cares?' The experiences of caregivers of adults living with heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and coronary artery disease: a mixed methods systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018 Jul 11;8(7):e020927. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020927. PMID: 29997137; PMCID: PMC6082485.

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IXc-!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9f7142a0-6602-495d-ab65-0e4c98cc67d4_450x450.png)

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lBsj!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0e0f61bc-e3f5-4f03-9c6e-5ca5da1fa095_1848x352.png)