How should we deliver kidney care in rural America?

Updated insights on the models, policies, and infrastructure shaping kidney care for 60 million Americans in 86% of the country

Editor’s note: This is an updated version of an October 2023 Signals piece, revised with new data, recent legislation, and fresh examples from across rural kidney care.

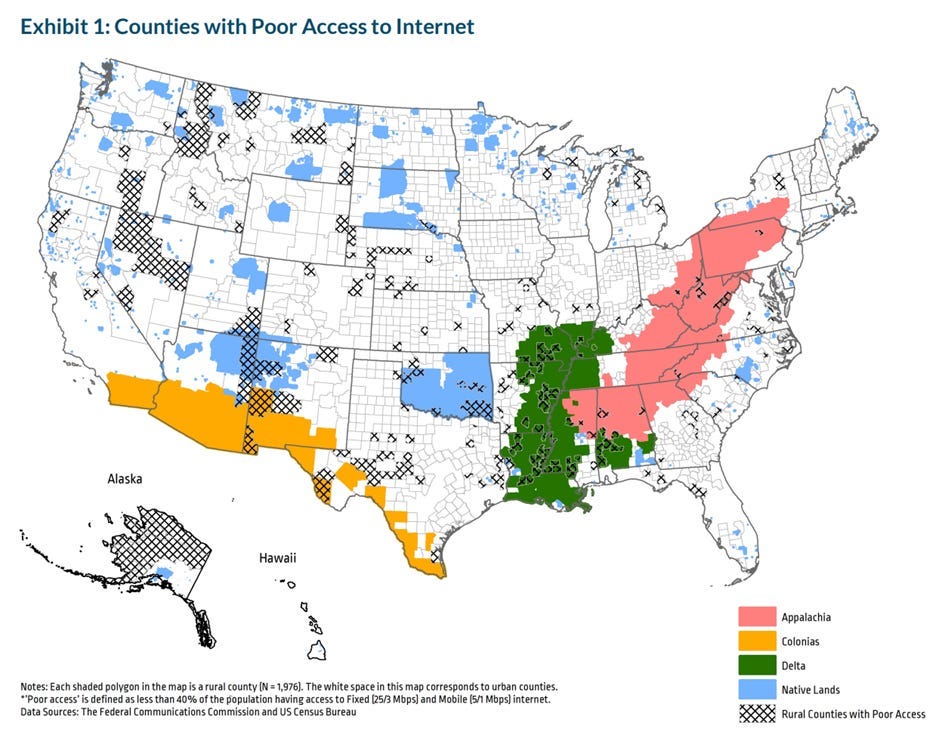

One in five Americans and about 86% of the land area in the United States are considered “rural.”1 In the vast landscape that is America, chronic diseases cast long shadows, affecting peoples’ lives in real, complex and inequitable ways. They are the leading causes of death and disability in this country; and yet, these battles are louder in some corners of the country than others.2 Providing quality healthcare for these 60 million people comes with a distinct set of rural challenges: a shortage of healthcare workers, limited access to specialists (including kidney doctors), and daunting distances to reach care. That is only part of the story. When we consider the growing diversity of rural America, along with the pending impacts of new federal legislation, it becomes clear that improving rural kidney care may be one of the defining challenges of our time.

Today, we continue our weekly journey into the heart of kidney health through the lens of rural care. We begin with two stories shaped by decades of partnership, community leadership, and quiet persistence.34

What’s Inside

Lessons from the Zuni tribe on home based kidney care

How tele nephrology is extending kidney care to five million rural veterans

Why digital connectivity is now essential clinical infrastructure

What new federal policy might mean for rural kidney care

Where we go from here (comment below!)

The Zuni Tribe

Our first story is nearly 30 years in the making. In 1995, a Zuni governor needed a kidney transplant and sought care in Albuquerque. It was then that University of New Mexico (UNM) researchers learned members of the Zuni tribe are 18.5 times more likely to develop kidney failure.5

Fast forward to 2013, when a team of researchers and Zunis co-designed a Home-based Kidney Care (HBKC) treatment program for adult Zuni Indians living with CKD in rural New Mexico. The team employed community health representatives (CHRs) under physician supervision to deliver culturally tailored, state-of-the-art health care in the patient’s home environment.6

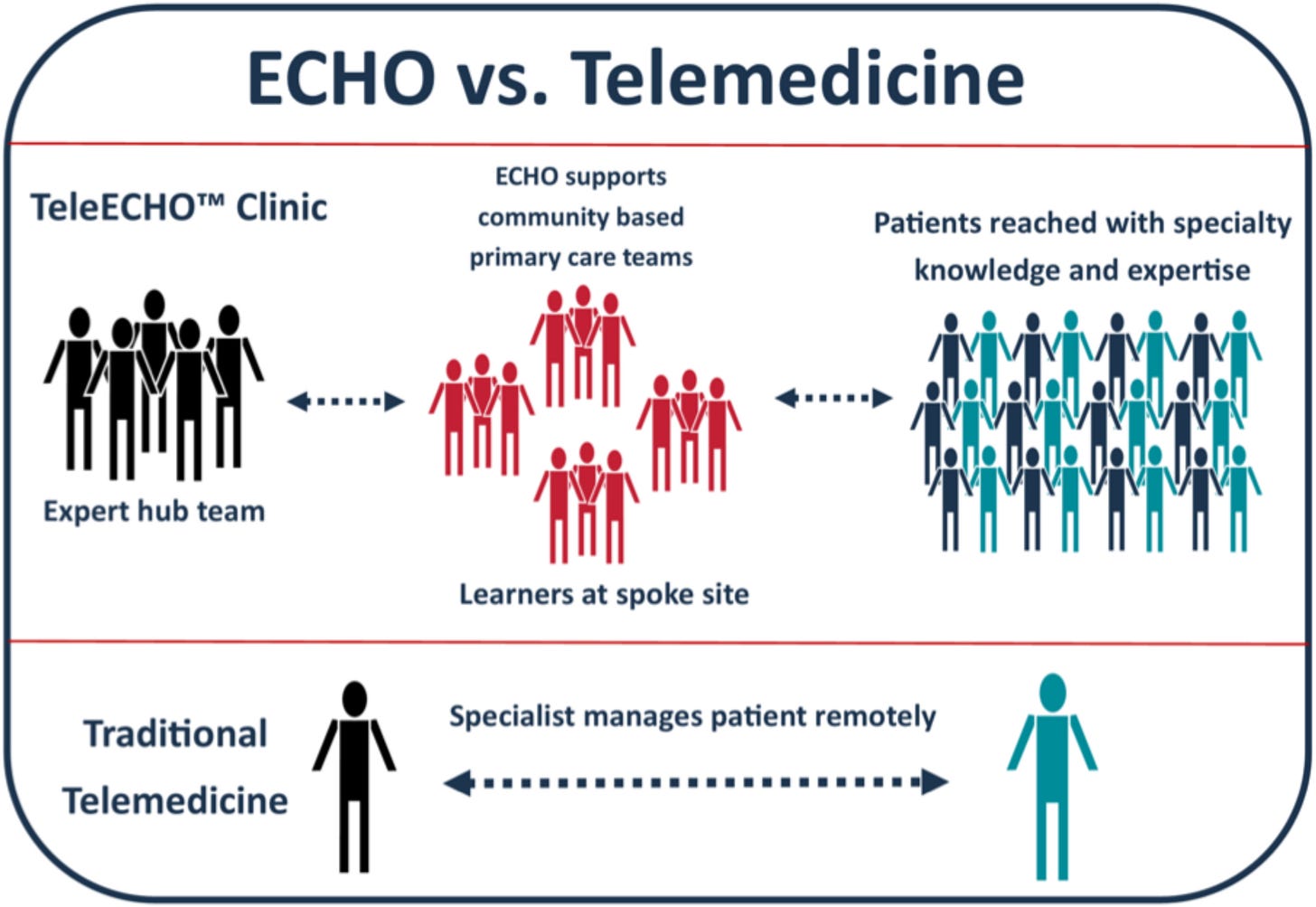

Figure: The ECHO Model vs. Traditional Telemedicine

Key Points

The program had (5) major interventions: (1) biweekly home visits; (2) tailored lifestyle coaching & education; (3) point-of-care (POC) lab testing; (4) daily motivational text messages for the first four months; and (5) telehealth services based on the Project ECHO model.

Trained Zuni CHRs were vital. They completed extensive training in lifestyle coaching, diabetes prevention, and diet and exercise change, which played a key role in delivering the interventions (daily texts, bi-weekly visits, lab tests, education) and support for participants.

Awareness first and always. The study involved extensive community outreach, including news outlets and education sessions in schools, senior and wellness centers, and other community events and locations. The research team also maintained regular meetings with CHRs, tribal leaders and advisory panel members who helped design the program.

Results: The HBKC program improved participants’ activation in their health and health care (primary outcome, measured by the PAM), and reduced markers of and risk factors for CKD (secondary outcomes, including BMI, A1c, and mental quality of life score).7 Dr. Shah and the UNM research team completed their study with 529 participants last fall and posted study results in April.8

Veterans Affairs

I receive my health care through the Department of Veterans Affairs, alongside more than nine million other veterans in the largest integrated health system in the country. It turns out the VA has a rich history of pioneering advances in kidney care, including the development of the AV fistula and the nation’s first organized dialysis program.

Chronic kidney disease is now the fourth most common diagnosis across the VA, yet access to specialist care remains uneven, especially in rural areas. More than five million veterans live in rural communities, and although they face higher rates of kidney disease than the general population, few are able to see a nephrologist before their health declines. Only 38 percent of veterans with CKD meet with a kidney specialist before reaching kidney failure, and one in ten new dialysis patients in the United States each year is a veteran.910

To close this gap, VA researchers created a tele-nephrology program built on a hub and spoke model.11 Nephrologists based in major centers such as Boston and Connecticut support patients in spoke sites across Maine, New Hampshire, Colorado, and Montana, allowing veterans to receive specialist care without traveling long distances.

The RE-AIM Study

A 2023 study of that VA tele-nephrology program provides helpful insights on perceptions and experiences among (14) staff members and clinicians at (5) spoke sites. Here are 5 takeaways using the RE-AIM framework:

Reach: Active engagement of a centralized clinical champion was a key factor in early success of tele-nephrology program.

Effectiveness: Transition from community-based nephrology to VA tele-nephrology was heralded as the most meaningful indicator of the effectiveness of the intervention.

Adoption: Effective adoption strategies included bi-weekly training with Hub nephrology staff and engagement of nurse practitioners.

Implementation: Meeting the needs of Veterans through proper staffing during tele-nephrology examinations was a key priority in facility program implementation.

Maintenance: Growing reliance on Hub nephrologists may give rise to insufficient availability of nephrology appointments in some Spoke sites.

According to the VA, the TeleNephrology program launched in 2020 and now provides care to more than 1,500 veterans with kidney disease. More than 90 percent of those veterans return for follow up visits through the program.

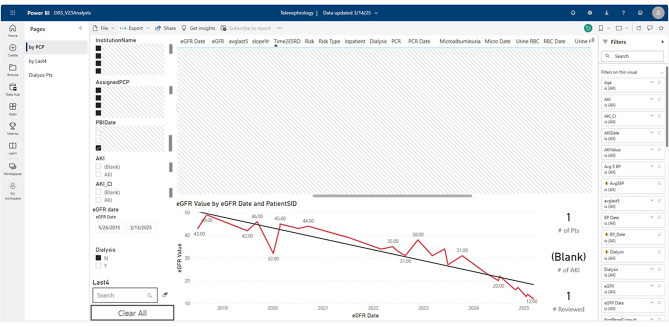

One recent initiative in Iowa City, which serves more than 150,000 veterans, is focused on optimizing clinical dashboards to support clinicians who rely on practical tools during remote visits. Members of the Iowa based team also presented new research at Kidney Week this year. Their qualitative study highlighted primary care’s central role in rural VA kidney care and described persistent, multifactorial barriers shaped by structural, operational, and digital access challenges. Primary care clinicians recommended expanded virtual support and more tailored education to better meet the needs of rural veterans.

Policy Landscape

A recent AJKD review by UNM and VA researchers put it plainly: rural CKD disparities won’t improve without expanding telemedicine, strengthening primary care training, improving care coordination, and building systems for early detection and prevention. But all of those require reliable connectivity, a trained workforce, and incentives that reward prevention rather than crisis care.

These are the types of needs that require policy solutions, which brings us to the topic on all those minds paying attention to this space.

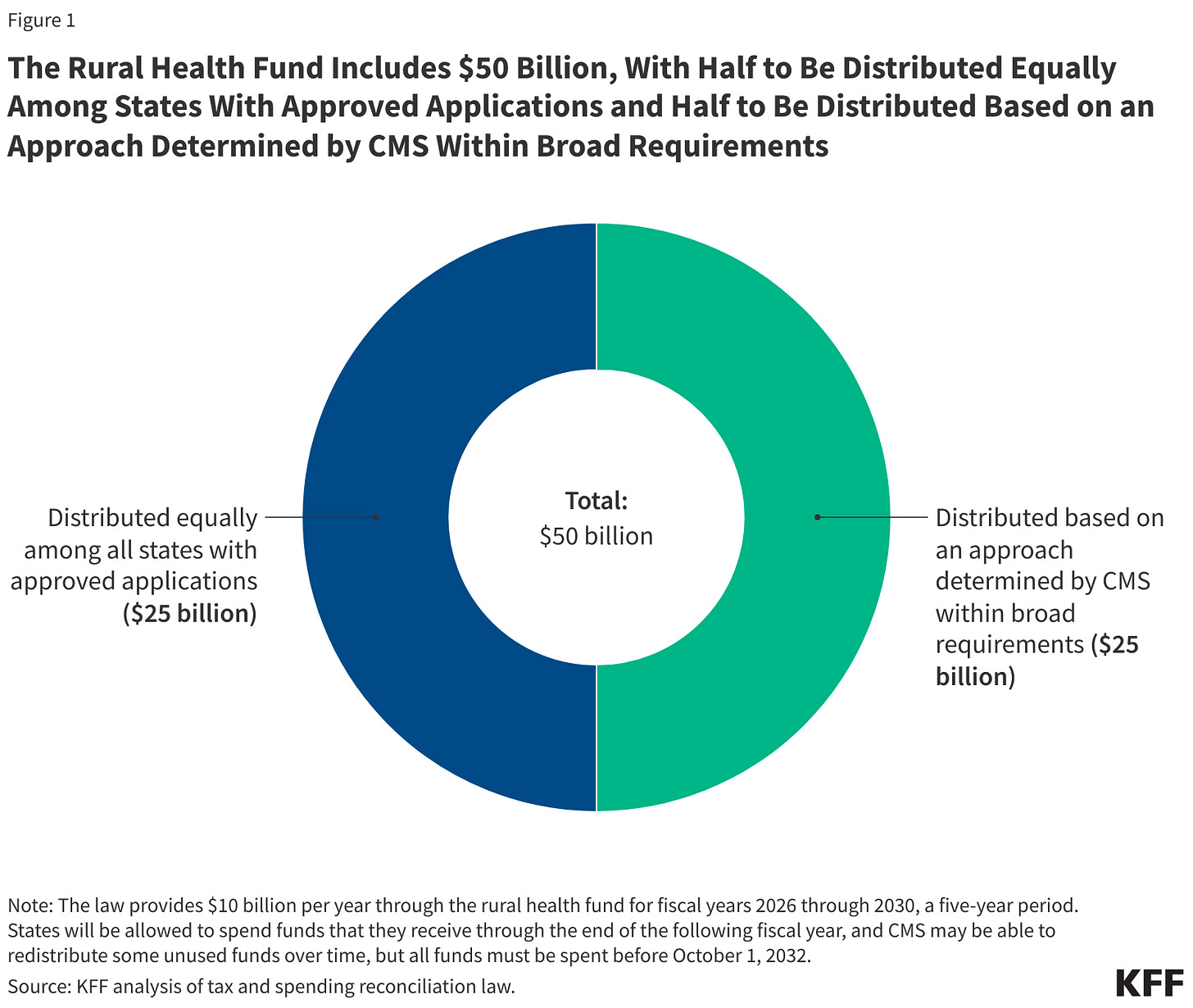

Policy is shifting, bigly. In July, President Trump signed a sweeping bill into law that includes $911 billion in Medicaid cuts over ten years and an estimated 10 million more uninsured by 2034.12 Rural hospitals were at the center of the debate as policy makers grappled with the potential toll on America’s sixth largest employer, especially as hospital closures have accelerated in recent years. In response, the Senate added a $50 billion “Rural Health Transformation Program,” providing $10 billion annually from 2026–2030 to help states modernize care, expand workforce programs, support digital infrastructure, and deploy remote monitoring.

But the math is sobering. The fund offsets only 37% of the expected Medicaid cuts to rural areas and it expires by 2030, years before most of the cuts take effect. Funding will be distributed before the full financial damage shows up, and states will receive equal amounts regardless of rural population or need. That means Connecticut and Kansas could receive the same base allocation despite one having 3 rural hospitals and the other nearly 90.

Recent modeling by the National Rural Health Association and Manatt reinforces this gap. Even if every dollar of the rural transformation fund went exclusively to rural hospitals, it would not fill even half of the Medicaid funding shortfall created by the bill. In Kentucky, the fund might replace ~$1 billion of a $5.4 billion projected gap. In Iowa, it fills less than a quarter of expected losses.13 The pattern is consistent across many southern and midwestern states with large rural populations.

The National Kidney Foundation also raised strong concerns about the law’s kidney-specific consequences. In a statement following Senate passage, NKF’s Senior Vice President for Health Policy, Dr. Jesse Roach, noted that nearly 300,000 dialysis patients rely on Medicaid and that new work requirements, copays, and reductions in provider taxes could increase the risk of patients losing coverage or delaying care. He warned that these provisions may “save money on paper” yet ultimately lead to poorer outcomes, higher downstream costs, and greater strain on rural hospitals and dialysis clinics.

Senator Bill Frist framed it well earlier this year:

“Many rural Americans aren’t dying because they can’t get to a doctor. They’re dying because of what happens long before they need one.”

Housing, transportation, food access, income, education, and internet access are core drivers of rural health inequities. The future of rural care will rely less on large inpatient facilities and more on connected networks that meet patients where they live.

Rural kidney care will be no exception.

Why It Matters

Rural Americans face a different kidney disease reality. They are more likely to develop CKD, more likely to be diagnosed late, and more likely to start dialysis in crisis. At the same time they have the fewest tools, specialists, and health system supports to change that trajectory. Nearly 240,000 rural Americans already live with kidney failure, and rural dialysis patients continue to have higher mortality rates regardless of where they receive treatment. This is a troubling signal because it points to broader structural gaps rather than differences in individual facilities.

The recent AJKD review makes this even clearer. Rural patients face obstacles shaped by poverty, long travel distances, and limited access to care. Disparities show up across every stage of kidney disease including CKD detection, in-center dialysis, home dialysis, and transplantation. The review outlined strategies rural communities need most: stronger preventive care, better CKD training for primary care clinicians, expanded telemedicine and telemonitoring, and more support for the rural health workforce.

These challenges often stay hidden until the tide goes out. Structural determinants and connectivity gaps shape the clinical realities we see in the exam room and in the annual cost reports. We talk about low awareness driving exponential cost curves, yet digital approaches cannot scale when large parts of rural America cannot reliably connect.

These gaps show up in the daily lives of clinicians. One rural nephrologist said it best:

“Many rural hospital laboratory and clinic systems are siloed off electronically and rely solely on fax for exchange of information. This also leads to delays in care under the best circumstances, or worse, the ball gets dropped completely.”

Policy decisions will shape these realities for years to come. As outlined above, the newest federal legislation creates both opportunities and risks for rural systems. Investments in digital infrastructure and workforce support matter, yet many of the deeper funding pressures facing rural communities remain unresolved. Rural kidney care will ultimately rise or fall on whether we can align care delivery, infrastructure, and incentives with the lived reality of rural patients. We also need clarity on how CMS plans to exercise its discretion in reviewing applications and allocating funds. States and local communities cannot plan effectively without knowing how those decisions will be made. That unknown still looms large.14

Still, the signal is clear. Rural kidney care is being shaped by clinical, structural, financial, and geographic forces at the same time. Even so, the Zuni HBKC program and the VA tele-nephrology model show what becomes possible when care is aligned with the realities of rural life. Local capacity building, trusted messengers, better primary care support, and reliable digital tools can move kidney care much earlier in the disease course.

The question now is whether we can build systems and infrastructure that give rural patients a real chance long before kidney disease becomes a crisis.

What Happens Now?

Kidney care is a massive and growing piece of our health care system, yet for 60 million people, it remains out of mind and out of reach. A path forward exists. The ingredients for better rural kidney care are already visible in the examples we just explored, and, in many cases, available to implement in your practice and local community.

To deliver kidney care in rural America, we will need:

Early detection systems that live inside primary care, not far from it.

Workforce support for CHRs, APPs, and PCPs who carry the bulk of rural CKD care.

Upstream payment models that outlast temporary grant programs.

ECHO-style capacity building, not just more telemedicine visits.

Digital infrastructure that treats broadband like a clinical prerequisite.

Kidney care touches every corner of America, but for rural patients, it remains the furthest away. Closing that gap will take the same thing it always has: trust, partnership, and a willingness to build care around the realities of the people we serve. I’ve seen that commitment firsthand in groups supporting rural hospitals and primary care teams, including TeleNeph and Renasolve, and in organizations strengthening local care models, like the team at ChenMed.

Keep exploring, and keep going. If you have another example, story, or question to share, add it in the comments below.

Thanks for being here with us.

Signals is free to read thanks to sponsors who stand behind this growing community of kidney care advocates, clinicians, industry leaders, researchers, policy makers & more. Share it with friends and peers in kidney care, and reach out if you’d like to learn more about partnering with Signals in 2026.

Ibid.

I refer to this KFF piece and related series quite a bit in this updated article as of November 2025. I want to thank all those who have helped pull that work together over the past many months as the policy and payment environments remain kinetic and ill-defined.

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IXc-!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9f7142a0-6602-495d-ab65-0e4c98cc67d4_450x450.png)

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lBsj!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_48,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0e0f61bc-e3f5-4f03-9c6e-5ca5da1fa095_1848x352.png)