The State of AI in Kidney Care

From “intellectual lightsabers” to nephrology uptake and legal risks, here's what we learned at the 2025 RPA AI Summit

This past weekend, I was invited to attend and participate in the 2025 RPA AI Summit, held as part of the Renal Physicians Association’s Advocacy & Innovation Weekend in Washington, D.C. The energy and engagement in that room were remarkable, and I’m grateful to have been part of it. My thanks to RPA President Dr. Gary Singer and Subcommittee Chair Dr. Virginia Irwin-Scott for organizing such a thoughtful program, and to the RPA Board for the opportunity to moderate two panels and share ideas with the broader kidney innovation community. This post highlights what I learned on Saturday. Thanks for being here and drop your questions below!

By Topic:

1. AI Beyond The Chatbot

Virginia opened the AI Summit with a fantastic lecture on the history of artificial intelligence and its current uses and limitations in healthcare. She’s perhaps uniquely positioned to give that talk, as both a member of the inaugural class of ACAIM fellows and the National Director of Kidney Care at ChenMed. As she and I have discussed before, there are few places in American healthcare where trust and access barriers are as visible as they are in ChenMed markets. That makes her dual perspective, as a physician leader caring for people with complex needs, and as the RPA’s QSA and AI Subcommittee Chair, especially valuable.

Virginia grounded the discussion in first principles: AI is only as strong as the data and context behind it. She reminded the audience that large language models, for all their sophistication, are still built on public data and cannot reach their full potential in healthcare until they’re coupled with the vast stores of structured and unstructured clinical data held by health systems—more than 30% of the world’s data. To illustrate both the promise and limits of today’s technology, she shared a story that had the room laughing. On Monday, she said, she gave her AI assistant all the data and training parameters it needed to build a model to risk-stratify a cohort of synthetic patients. By Tuesday, it had created an impressive linear regression model. But by Wednesday morning, when she returned to refine the work, it had completely forgotten her and replied, in so many words, “New number, who’s this?”1

It was a perfect metaphor for where we stand today: impressive early progress, but plenty of work ahead to make AI as reliable, contextual, and accountable as the people using it.

2. AI State of Play

The AI State of Play panel brought together four physician-leaders shaping how artificial intelligence is being built and deployed across kidney care: Natalia Khosla (Simbie AI), Alice Wei (Nephrolytics), Qasim Butt (DeLorean AI), and Stephanie Toth-Manikowski (Healthmap Solutions). The conversation focused on the realities of implementation—where progress has been uneven, but momentum is building. On the topic of “Trust but verify”, Qasim drew laughs with his observation that “the older generation struggles with trust, while the younger generation struggles with the verify part,” before admitting that even with access to the top AI scribes, he still prefers his own notes. “They just don’t write like I do,” he said—a sentiment that echoed later when another speaker described AI scribes as making them sound like “a really smart third-year medical student.” The trade-off between efficiency, accuracy, and authenticity framed much of the discussion around where AI helps and where it still falls short.

From a recent review in Kidney News:

Despite promising signs that AI can produce largely accurate responses, the study shows that current tools are not yet ready to replace clinical conversations in nephrology. Notably, the accuracy of AI outputs tends to diminish as clinical questions become more specialized… These limitations are particularly consequential in the context of diabetic nephropathy (DN), for which decisions about disease progression, timing of interventions such as dialysis initiation, and tailoring of treatment strategies require sophisticated clinical judgment. A chatbot, regardless of its algorithmic prowess, cannot yet replicate that.2

As the lone non-nephrologist on the panel, Natalia Khosla brought a valuable broader lens from her work with Simbie AI that provides voice agents to practices to help with things like intake, registration, education, and even medication refills. She highlighted both the promise and the practical roadblocks, like how many practices don’t have a baseline understanding of the metrics AI tools aim to improve, complicating the case for adoption and ROI. She also used her platform to call for physician advocacy, especially around payment reform and the need for physicians to shape how these tools are built and delivered—a point that drew multiple rounds of applause!

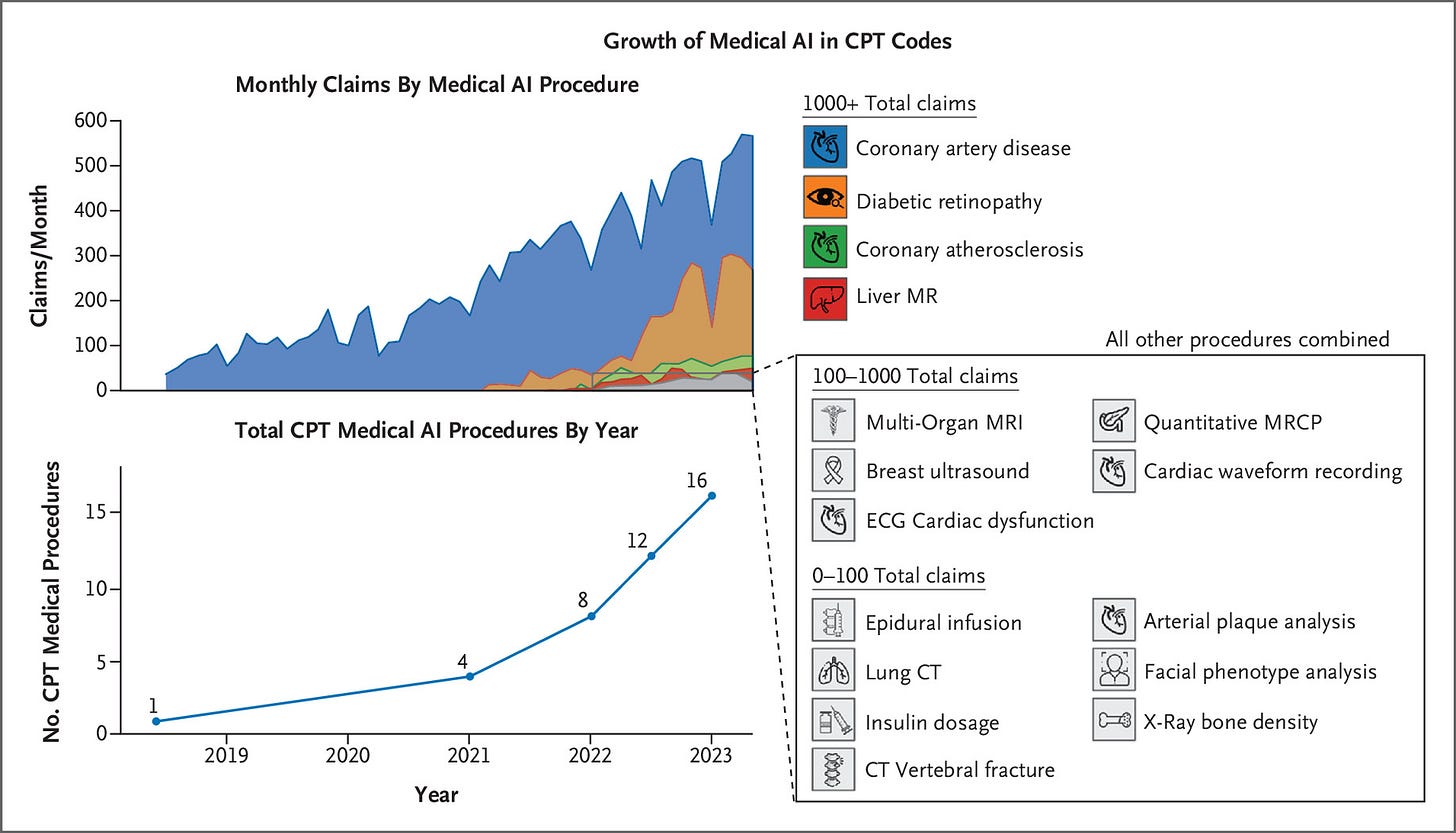

Alice Wei added that while predictive models have matured, the hard part isn’t building them, it’s implementing them. “Tools are great if someone will pay for it,” she said, underscoring the disconnect between getting CPT codes and actually billing for services. The first AI-specific CPT code, established in 2021 for the autonomous detection of diabetic eye disease, marked a milestone in how AI-driven diagnostics could be reimbursed. Still, CPT codes alone are not a viable commercial strategy. Fragmented data ecosystems remain one of the biggest barriers to scaling AI’s potential impact, beyond the change management that comes with rolling out new platforms in a specialty dominated by exacting humans and longstanding treatment paradigms.

Figure: Growth of Medical AI in CPT Codes

Looking ahead, the panel agreed that success will require more than early champions—it will take shared ownership across physicians, data scientists, and data owners to ensure AI augments, rather than replaces, human expertise. The “predict, summarize, prioritize, and parse” framework captured how AI could reshape the physician workflow, freeing clinicians from the administrative weight that too often pulls focus from patients.

The takeaway is clear: these tools will eventually be nearly everywhere, but not yet. And right now is the moment for clinicians to shape them—to make sure they enhance what medicine does best and take on what it doesn’t. Whether it’s two years or ten, nephrology itself may look very different because of AI, and the challenge now is to be ready for it.

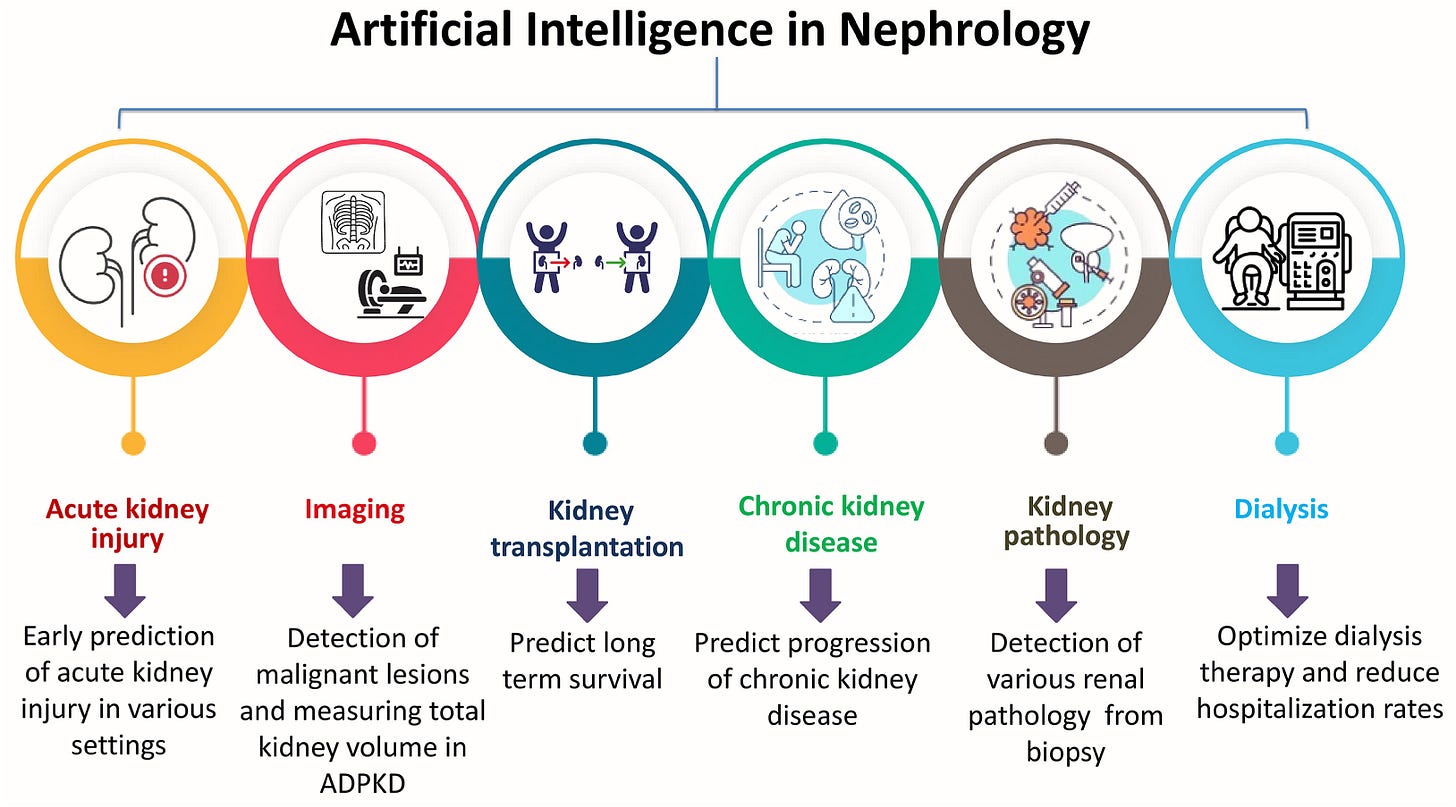

Figure: Select AI Use Cases

3. AI Legal Implications and Risks

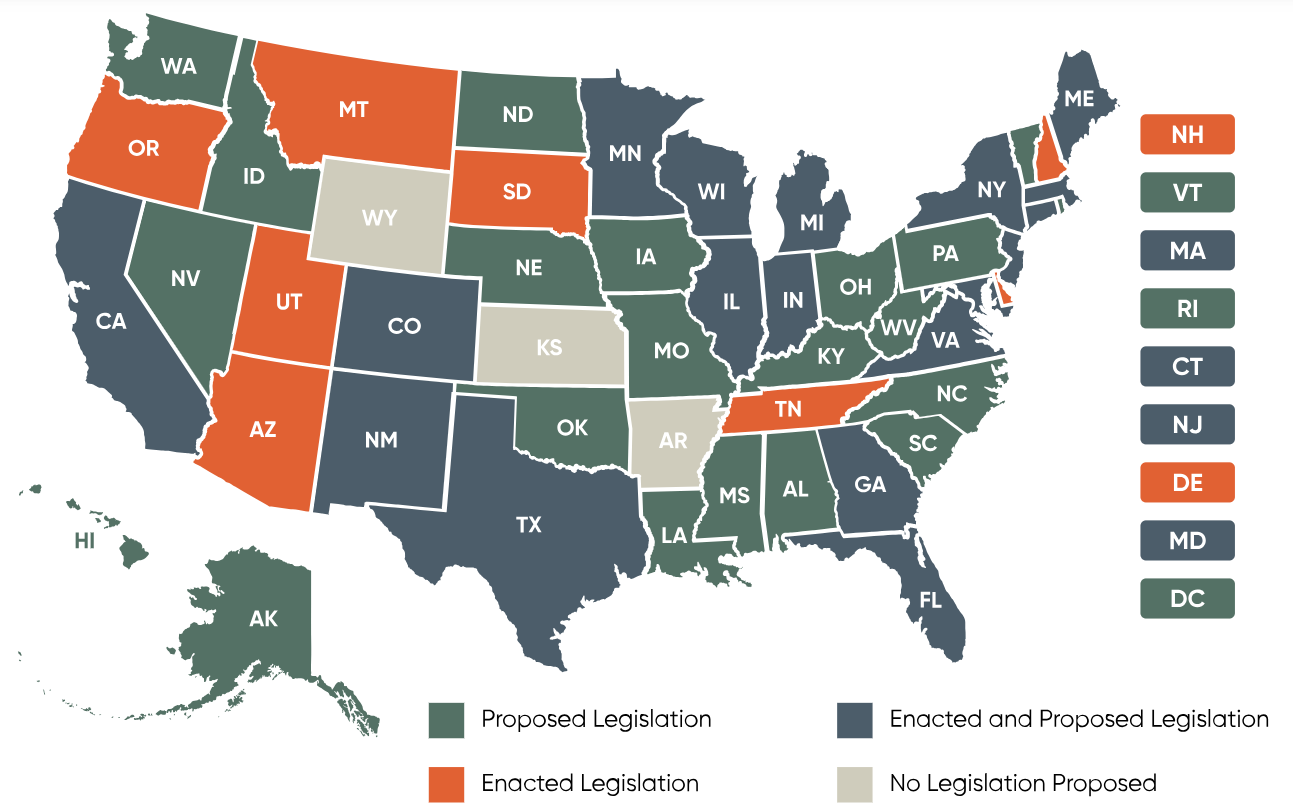

Another standout session came from Nick Adamson of Benesch Law, who broke down the emerging patchwork of AI regulation and liability in healthcare. He opened with a reminder that at the federal level, “regulation is at a stalemate,” with most legislative movement coming from the states. Texas, Colorado, Utah, and California have each passed AI-specific bills this year, defining how health systems, payers, and vendors must disclose AI use, maintain human oversight, and document risk. have each passed AI-specific bills this year, addressing everything from disclosure and human oversight to liability and recordkeeping. These new laws are beginning to establish consistent expectations for transparency, auditability, and enforcement, but they may also shift more responsibility onto providers and systems that deploy AI. As Nick noted, “it’s not enough to know what your AI can do—you have to know what your state expects you to know.”

Figure: State-by-State AI Legislation

Nick also outlined the growing list of liability risks tied to AI, from malpractice and consumer safety statutes to the enforcement of existing healthcare laws like Stark and anti-kickback. A recent headline out of Texas underscored his point: the state attorney general reached a settlement with an AI company for misleading marketing claims about clinical accuracy, marking the first state level AG settlement against an AI tool.

As Manatt put it:

It’s an important reminder that states do not need new legislation to regulate the use of AI.

Nick closed with four best practices for any organization deploying AI:

Write clear internal policies on who can use AI, which tools are approved, and in what contexts.

Obtain patient consent when using AI in clinical or administrative workflows.

Update contracts and BAAs to include AI-specific protections around data use and reliability.

Ask vendors about their AI use to understand risks, data practices, and safeguards.

His overarching message was pragmatic: AI isn’t a solution, it’s a tool—and one that brings new accountability. Staying compliant will mean treating AI oversight as an ongoing governance responsibility, not a one-time checklist.

4. EHRs and Workflows

Moving from courtrooms to the clinic, Adam Weinstein’s talk explored how artificial intelligence is beginning to augment, rather than replace, the clinical reasoning process in chronic disease management, especially in nephrology. “AI offers infinite memory and contextualization,” he noted, framing it as a new kind of partner in care that merges content science, data science, and clinical judgment. His slides showed how AI can now interpret everything from lab results and vital signs to free-text notes, bridging structured and unstructured data. Large language models (LLMs) make it possible to summarize, synthesize, and even suggest next steps in complex cases like CKD.

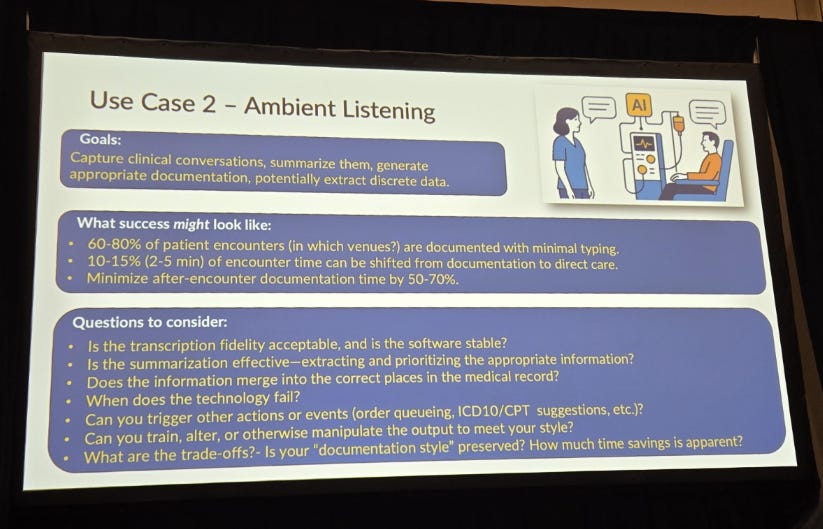

Figure: Use Case #2 - Ambient Listening

Adam outlined three key use cases already reshaping workflows: risk prediction models that identify which high-risk patients need attention first; ambient listening tools that capture and summarize clinical encounters, freeing up physicians from hours of documentation (see above); and data summarization engines that condense years of medical history into concise overviews for faster decision-making. When deployed safely, success might look like reducing chart review time by 20–50%, streamlining documentation by up to 70%, and making longitudinal patient trends visible at a glance. But he also emphasized that every gain must come with “a human in the loop,” clear data provenance, and measurable governance guardrails.

In closing, Adam likened AI to “an intellectual lightsaber” of sorts: powerful, but requiring skill, governance, and restraint. He also joked about the risk of “accidentally cutting off limbs,” which is why, he said, we need to be careful (point well taken). The excitement lies not in replacing clinicians but in amplifying their cognitive bandwidth, helping them see patterns sooner, act faster, and deliver more personalized kidney care. Governance, training, and user education “cannot be optional,” because these systems are only as safe and effective as the humans guiding them. Just imagine if we had all grown up with stories of humans and LLMs thriving together in this big, uncertain world (see below). Someone should write that book.

5. Payers’ Use of AI

In her session, Heather McComas from the American Medical Association (AMA) explored how payers are using artificial intelligence to manage care decisions and administrative processes across healthcare. She outlined findings from a recent National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) survey, which found that 84% of insurers now use AI or machine learning in some capacity, primarily for utilization management and prior authorization decisions. However, she noted that transparency remains limited—only about 1 in 4 insurers report disclosing to physicians when or how these tools are being used.

Figure: Physician Impact of Prior Authorization (PA)

A major area of concern was the use of AI in downcoding programs, where payers automatically downgrade evaluation and management (E/M) services based on diagnosis codes and limited claim data, often without medical record review. The AMA warned that this lack of transparency can exacerbate both revenue challenges and administrative burdens for physician practices. The conversation also touched on the importance of governance and physician oversight, including bias testing, temporal validation, and clear human review to ensure AI augments rather than replaces clinical judgment.

As you might imagine, the recently announced WISeR model came up a few times throughout the day. That’s the new Medicare pilot program that uses AI and machine learning to review certain services for their medical necessity with the goal of reducing waste, fraud, and abuse. It’s classified as a voluntary model, but is effectively mandatory for providers and suppliers in certain states. A recent perspective piece in NEJM points out that “broadly expanding prior-authorization requirements in traditional Medicare — and relying on decisions by private companies that stand to profit from care denials — warrants careful oversight.”

Figure: What’s The Cost of Prior Auth?

The takeaway: payers are rapidly becoming some of the most sophisticated AI users in healthcare, not only to manage costs but to automate decisions that affect patient access and physician workflow. The coming challenges will be many, but top of mind for this group is balancing efficiency with fairness—and ensuring that algorithmic precision doesn’t come at the expense of transparency, trust, or patient care.

6. AI in the Real World

The closing panel on AI in the Real World brought the full spectrum of adoption into focus—from Vijay’s hands-on use of custom GPTs to refine decision-making in his nephrology practice, to Jason Kline’s experience at Cooper Hospital, where AI is just beginning to appear in clinical research and nursing workflows. Adam and Dana offered the perspective from DaVita, where the challenge isn’t enthusiasm but scale—navigating a complex network of clinics, data systems, and varying state regulations that make large-scale AI deployment far from simple. Together, their stories showed how AI familiarity varies widely across the field, from those experimenting daily to those just beginning to explore what’s possible.

The conversation quickly turned to how innovation happens in environments built to avoid risk. For many organizations, implementation sits at the intersection of enthusiasm, care-delivery setting, and operational readiness—if even one side of that triangle is missing, progress stalls. Adam noted that rollout challenges often show up in two camps: those who push the limits of a tool’s use case, and those who trust it too blindly (“if a computer said it, it must be true”). The result is a reminder that successful adoption requires both curiosity and critical thinking. And as Dr. Brendan Bowman asked during Q&A, a larger question looms: what happens when platforms like Epic or Microsoft decide to build competing tools? What does that mean for emerging companies developing these technologies—and for incumbents already deploying them? AI in healthcare is no longer about whether it will be used, but how it will be integrated responsibly amid bureaucracy, variability, and potential consolidation.

Before we wrapped up, I asked the audience a few quick questions: how many were using AI in their personal lives? Nearly every hand went up. For work? Just as many. But when I asked how many nephrologists would describe themselves as early adopters of new technology in their practice, I’d say nearly a third of hands rose—a number that mirrors broader data on technology adoption among Americans. It may actually be good news for innovators, suggesting a growing but still approachable curve. The discussion underscored that while AI adoption in kidney care may look uneven today, it’s no longer a question of if—it’s how and when. The panel closed with an open invitation to keep learning, testing, and shaping the tools that will define the next decade of kidney care together.

I’d love to hear your take on these topics. Clinicians and patients, where does AI fit into your day to day? What questions do you have for the AI summit speakers and attendees? Founders, if you’re building AI solutions to address unmet needs in the kidney space, make sure your company is in the Signals Directory and say hello!

Episodic vs Persistent Memory in LLMs (labelstud.io)

Ebrahimi N, Vakhshoori M, Teichman S, Abdipour A. Agreement Between AI and Nephrologists in Addressing Common Patient Questions About Diabetic Nephropathy: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Diabetes 2025;10:e65846. DOI: 10.2196/65846.

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IXc-!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9f7142a0-6602-495d-ab65-0e4c98cc67d4_450x450.png)

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lBsj!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_48,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0e0f61bc-e3f5-4f03-9c6e-5ca5da1fa095_1848x352.png)

The scale challenges DaVita faces with AI deploment really highlight how different enterprise healthcare implementation is from pilot programs. When you're managing thousands of clinics across different regulatory environments, the complexity isn't just technical—it's organizational. Would be interesting to see if they take a phased rollout approach, maybe starting with states that have clearer AI frameworks like Texas or Colorado.

Very interesting Tim. Thank you for the wonderful work and explanation of this great but complicated subject. I love the article pointed out AI should be a complement to the Healthcare world, not work independently from the clinician. It was also not a huge surprise that billing has a huge foothold in AI