What Counts as a Timely Referral for Kidney Transplant?

Why GFR thresholds, access, and real-world practice don’t always line up.

When should patients ideally be referred for kidney transplant evaluation? It sounds like a simple question, but of course it isn’t. Before we get into the discussion, we need a quick look at how we measure kidney function.

Your kidneys filter your blood by removing waste and extra water to make urine. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) shows how well the kidneys are filtering, and it’s the main way health professionals gauge kidney health.

In this piece, we’ll just use “GFR” to mean this usual estimated GFR from a simple blood test.1

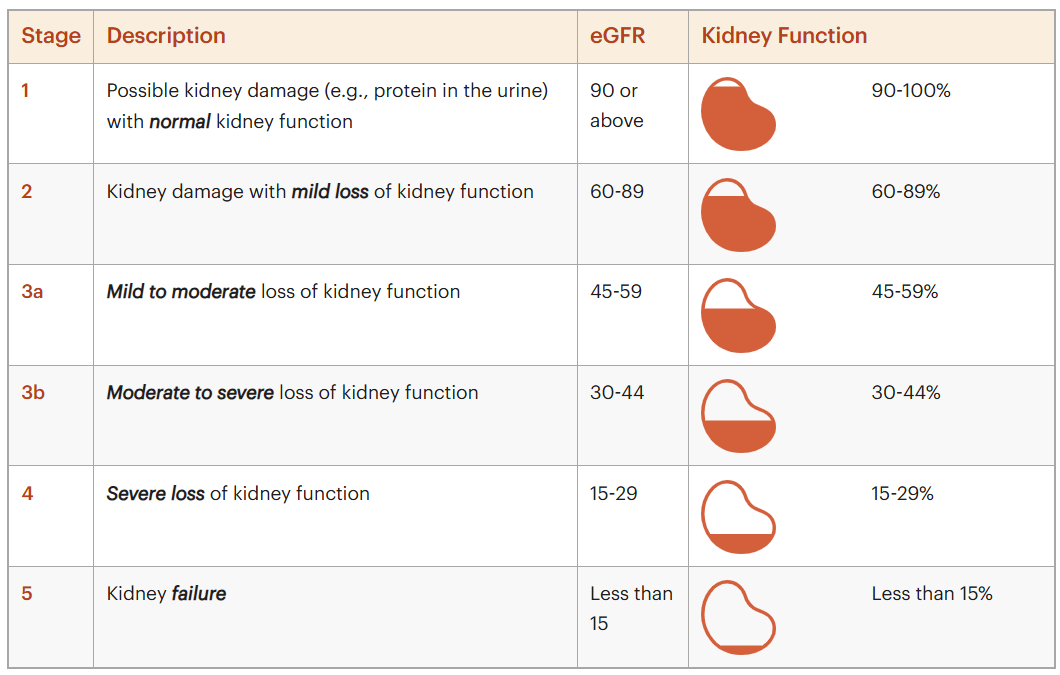

Figure: The Stages of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

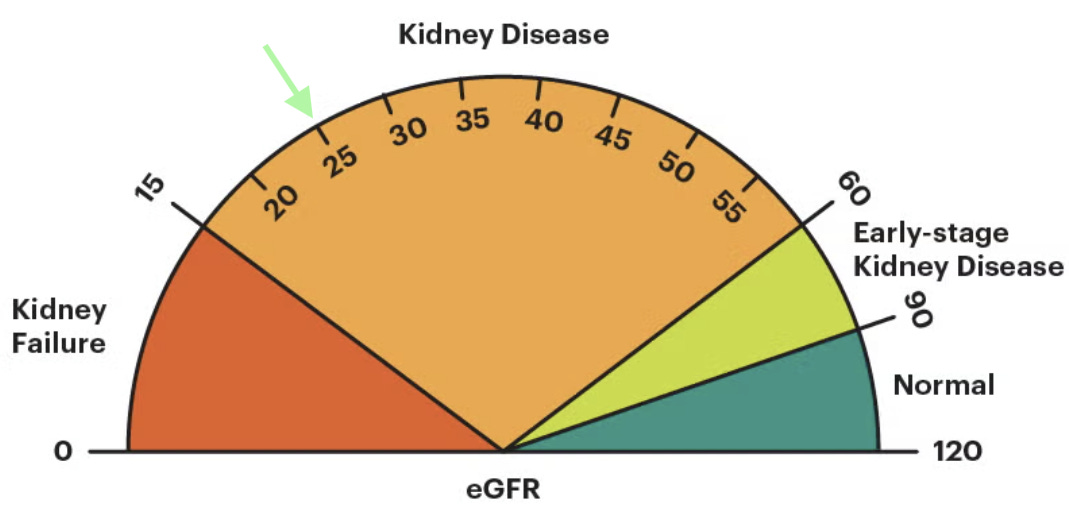

The lower your GFR is, the less kidney function you have. In adults, a “normal” eGFR is usually above 90, and it naturally declines with age, even in people without kidney disease. Clinical guidelines, including KDIGO, use GFR as a key signal to guide transplant referral decisions—particularly once GFR falls below 30 in patients expected to progress to kidney failure. But there’s an important caveat. GFR is a single snapshot from a blood test. It doesn’t show how fast kidney function is changing or capture the full risk of decline, which is where patient-level realities, transplant center capacity, and real-world practice patterns start to matter.2

Today’s conversation is about what happens as a patient’s GFR drops below 30 and moves closer to kidney failure; and how that timing shapes access to kidney transplant. Patients can be listed for a deceased donor kidney transplant when their GFR drops below 20. Their official waiting time on the list begins when they start dialysis or when their GFR falls below 20, whichever comes first.3 In 94% of cases, patients start dialysis before joining the waitlist.4 That needs to change. How and why that might change is at the heart of today’s discussion.

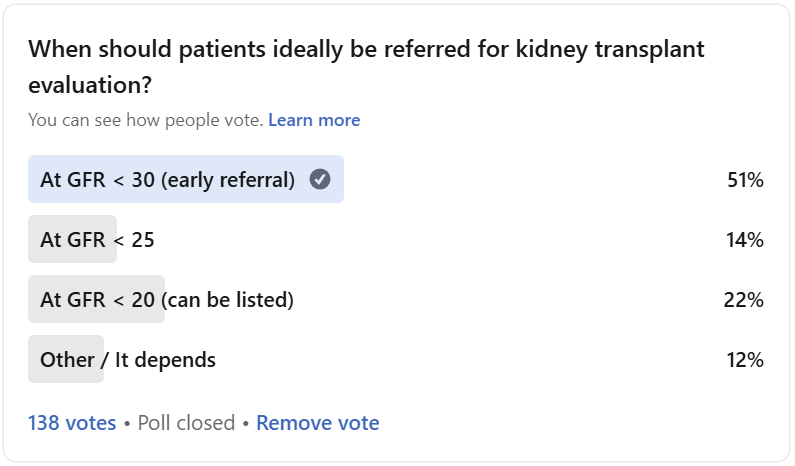

LinkedIn Poll Results

In my recent poll (n=138), just over half of respondents chose the earliest starting point, GFR <30, as the right time to start the transplant evaluation process. Others were split between <25 (14%), <20 (22%), or “it depends” (12%). We heard from a large number of nephrologists, nurses, patients and advocates on this one. The comments that followed surfaced something deeper than a single magic number: timing is about education, risk, system capacity, and language as much as it is about eGFR alone.

Here’s what we learned, starting with the majority of respondents.

GFR <30

The Case for Pre-Evaluation

KDIGO guidance recommends considering transplant referral once GFR falls below 30 for patients expected to progress to kidney failure, ideally 6–12 months before anticipated dialysis initiation. The goal is to allow enough time for education, evaluation, and, where possible, living donor identification and planning for pre-emptive transplantation.

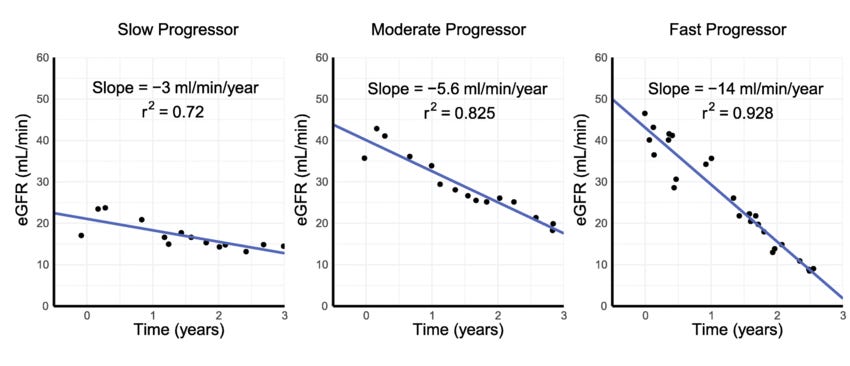

The challenge is that “expected to progress” is not a simple designation. KDIGO’s own CKD guidance reflects this complexity, emphasizing not just a single GFR value, but trajectory over time, albuminuria, and overall risk. In practice, this leaves room for interpretation—and helps explain why referral timing varies so widely even when clinicians are following the same guidelines.

Supporters of GFR <30 generally are not arguing that every patient should start a full transplant workup at that point. Instead, those who advocated for this approach (themselves recipients and nephrologists) see 30 as an ideal moment to begin education and planning. A GFR in the high twenties or near 30 provides time to explain the transplant process, set expectations for life after transplant, and start a structured search for a living donor. It also allows patients to choose a transplant center, understand options like multi-listing, and work through insurance constraints before time pressure sets in.

A few people framed this as a “pre-evaluation” phase. At or around GFR 30, teams could focus on teaching the listing process, identifying and addressing social, financial, and logistical barriers, and introducing the rationale and mechanics of living donation. Some argued that GFR trajectory matters as much as the absolute value: even if the number is above 30, a clear downward trend should trigger earlier conversation and planning. More on that later.

The downsides are practical. A hard 30 cutoff can capture many people who will never progress to ESRD, especially when risk markers like albuminuria or GFR slope are not considered. Full evaluations at higher GFRs can mean more long-term test maintenance, repeat imaging, and clinic time for patients who may stabilize. In already stretched programs, a “30 for everyone” policy risks overloading teams without clear evidence that transplanting earlier within CKD Stage 4 (i.e. well before kidney failure) improves mortality, even among recipients of pre-emptive living donor transplants.5

GFR <25

“The Middle Ground”

For others, GFR <25 represents a compromise between being early enough to matter and late enough to be workable. Using GFR <25 as a referral point was described as “timely but not too early”: it captures patients closer to the point where transplant is likely, while avoiding a larger pool of individuals who may never require kidney replacement therapy.

This threshold can also align better with payer expectations and testing cycles. Some clinicians report fewer insurance denials for pre-transplant testing at 25 compared with 30, and less need to repeat imaging or cardiac studies that might otherwise expire before the patient becomes eligible for listing. From the patient perspective, a threshold in the mid-20s still preserves meaningful time for education, living donor search, insurance review, and center selection.

The trade-off is a narrower runway. Compared with a true pre-evaluation phase at 30, referral at 25 compresses the time available to address complex barriers, particularly for those with rapid decline or limited support. It is “early enough” for many, but may already feel late for patients with high-risk features who could have benefited from structured engagement even sooner.

GFR <20

The Current Standard of Care

The GFR <20 position is usually grounded in policy, capacity, and evidence. This is the point at which patients qualify for transplant listing, so tying referral closely to this threshold can make operational sense. In many cases, referring just under GFR 20 still allows enough time to complete evaluation and identify a living donor before dialysis is needed, with transplantation often occurring once kidney function declines further.

Advocates for this cutoff point to supply–demand realities. In a system where the waitlist continues to grow faster than organ availability, they worry that shifting referrals much earlier could saturate evaluation pipelines without clear proof that transplant at higher GFR values meaningfully improves outcomes. Many centers simply do not have the capacity to absorb a large influx of referrals at 30, and the current evidence base for routinely transplanting at GFR >20 remains limited.

The risks are equally clear. A strict <20 approach can bring patients into the process too close to the "cliff”, leaving limited time to identify donors, resolve any insurance issues, and provide robust education before dialysis initiation. For patients with complex social circumstances or fast-progressing disease, waiting until 20 may mean trying to solve structural and informational gaps in a high-stress, compressed period. The fact of the matter is just getting listed takes months to years, and in a world where patients are having to wait 5 to 10 years for a new kidney while facing a 40% chance of survival at 5 years, every day counts.

“It Depends”

Let’s Talk Risk

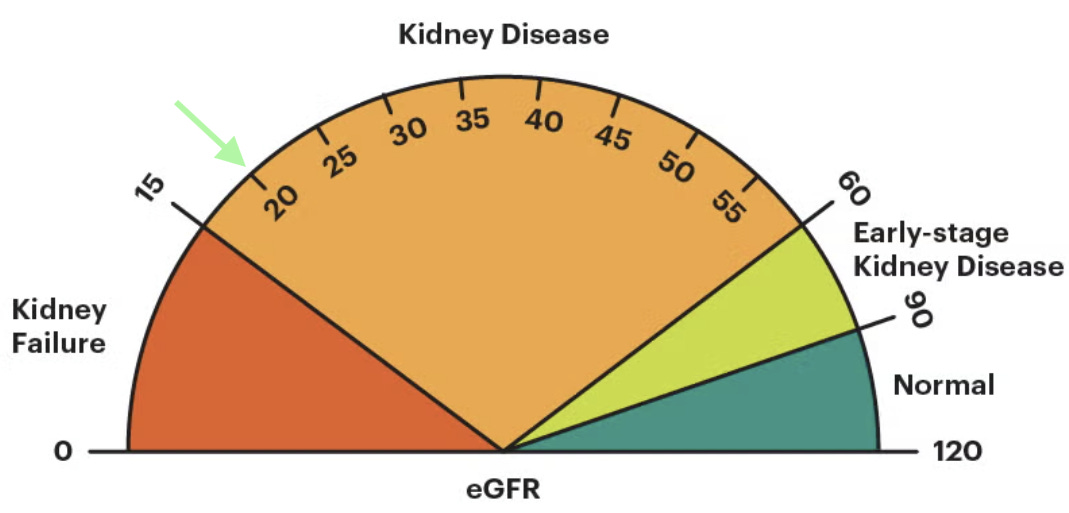

There is broad agreement that eGFR alone is an imperfect guide here. A number of people recommend risk-based thinking: for example, a patient with GFR 29 and heavy albuminuria may be at higher near-term risk than someone with a stable GFR of 18 and no albuminuria. GFR slope and overall ESRD risk scores were repeatedly mentioned as missing pieces in a pure-number approach. In this view, the central question becomes: What is this person’s risk of needing kidney replacement in the next 12–24 months? Some people say high-risk patients should be flagged and considered for transplant evaluation regardless of whether their GFR is currently above or below 20.

Language also surfaced as a key factor. Some respondents argued for emphasizing “timely” rather than “early” referral. “Early” can sound like doing something extra or outside the typical workflow; “timely” reinforces that referral should happen when clinical information indicates it is appropriate. In both transplant evaluation and organ donation, missed moments in communication can translate into lost opportunities, and wording shapes how clinicians perceive what is “standard.”

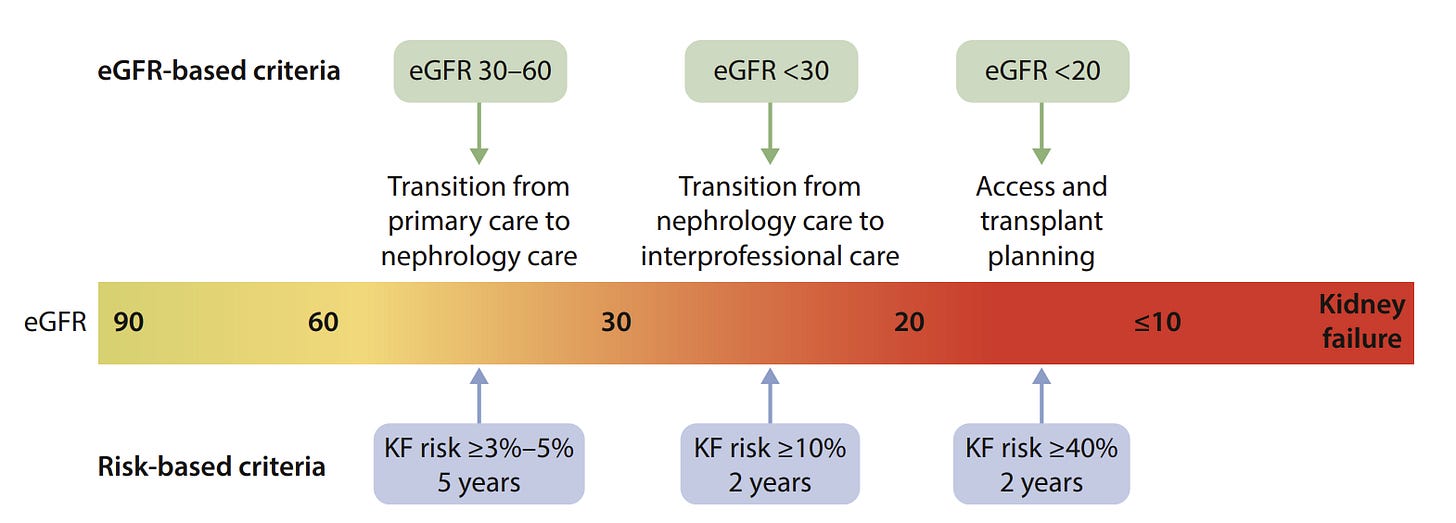

A third theme was technology and workflow. There was strong interest in using EMR tools and AI-driven stratification to systematically identify high-risk patients based on GFR, slope, albuminuria, and other markers, then nudge teams toward pre-evaluation or full evaluation as appropriate. Rather than relying on a single cutoff, respondents imagined a two-stage model, including:

a risk-based pre-evaluation track upstream (often around 30 or earlier for those at highest risk), focused on education and planning, followed by…

formal evaluation and listing closer to GFR 25–20, aligned with center capacity, insurance, and testing timelines that ensure candidates remain active.

Figure: Transition from an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)-based to a risk-based approach to chronic kidney disease care. KF, kidney failure.

Where do “referrals” actually happen?

This discussion often glosses over a basic question: who actually makes the referral? In practice, that responsibility usually sits with the nephrologist caring for the patient, whether in a CKD clinic or a dialysis center. And unlike listing criteria, there is no clear, standardized definition of what a “transplant referral” even is. It might be a formal order, a fax, a phone call to a familiar transplant program, an EpicCare Link, or something else. CareDx offers TxAccess to help streamline this challenge on the transplant center side. The point is this: referral mechanics vary widely.

That variability matters. Research has shown large differences in referral and preemptive transplant rates tied not just to patients, but to nephrologist characteristics and practice context—such as years since training, academic affiliation, and rural versus urban practice.6 In other words, referral timing is often shaped less by a precise GFR threshold and more by who is sitting across from the patient and how referral works in that system.

One important nuance: a formal physician referral is not required. According to OPTN, patients can contact a transplant program directly, and early evaluation—often around GFR 25–30—is encouraged even before dialysis.7 In practice, however, most patients never self-refer. They rely on their nephrologist and care team to raise the topic, explain the process, and initiate contact. That gap between what is allowed and what actually happens helps explain why referral timing varies so widely, even when there are no strict criteria for referral. But the OPTN does not mince words:

Preemptive transplantation is considered to be the most optimal treatment for [kidney failure] as patients are able to receive treatment before experiencing the medical complications and debilitating effects of dialysis.

Summary & Next Steps

Taken together, the discussion suggests that there is no universally “correct” GFR threshold that can be applied in isolation. GFR <30 offers time for education, donor search, and barrier removal, but can strain program capacity if treated as an automatic full-evaluation trigger. GFR <25 functions as a pragmatic middle ground, balancing timeliness with payer and testing realities. GFR <20 aligns with listing rules and acknowledges organ scarcity, yet risks leaving some patients behind if meaningful preparation only begins at that point.

The emerging pattern is less about picking a single number and more about redesigning how people actually move into transplant care. In practice, that looks like a smoother on-ramp into transplant: identifying higher-risk patients earlier, giving them time for education, planning, and donor conversations, then moving into formal evaluation and listing as kidney function declines and local capacity allows. The exact cutoffs will differ by center, but the principle is the same—use data to see trouble coming, give people enough runway to act, and avoid wasting scarce transplant resources.

What do you think? Share your thoughts, questions, or stories so others can learn from them. Thanks for being here with us.

My thanks to all those who participated in this weekly poll and weighed in the comments. Your input made this post possible. In particular, I want to thank those who provided additional insight and personal experience to help shape this piece. This includes Katie Kwon, Michelle Reef, Jullie Hoggan, Jameisha Nicole Rogers, Varun Chawla, Brent Shealy, Pesh Patel, Krishna Agarwal, and Chip Zachem. You might also enjoy my recent conversations with Jullie Hoggan and Michelle Yeboah, or recent writing by Dr. Karin Hehenberger and Jeanmarie Ferguson.

There are two ways to talk about kidney filtration: estimated GFR (eGFR), which is calculated from blood tests, and measured GFR (mGFR), which uses more complex testing and is less common in day-to-day practice. Transplant decisions can be based on either measured or estimated GFR. (OPTN Policy)

2024 KDIGO CKD Guideline (199-page pdf)

KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Management of Candidates for Kidney Transplantation (Supplement in Transplantation Journal)

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0041134525001459?via%3Dihub

“Pre-emptive kidney transplant remain at roughly 18% of total kidney transplant (33% were from deceased donors and 67% from living donors). White patients with a higher level of education and with private insurance were most likely to receive pre-emptive kidney transplant. No difference in mortality was found in the four eGFR groups. In a subgroup analysis looking only at recipients of pre-emptive kidney transplant from living donors, no mortality difference was again noted among the four groups.” (Transplantation Proceedings, 2025)

Q: Do I need a doctor’s referral, or can I contact the transplant program myself?

A: You can contact the hospital yourself. You don’t need a doctor’s referral, but your doctor may have test results and medical history that will make it easier for the transplant team to evaluate you.

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IXc-!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9f7142a0-6602-495d-ab65-0e4c98cc67d4_450x450.png)

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lBsj!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_48,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0e0f61bc-e3f5-4f03-9c6e-5ca5da1fa095_1848x352.png)