We Are Here: Five Charts That Explain the Current State of Kidney Care

From awareness to access, and dialysis to donation, here’s what’s actually changing— and where we're still stuck.

On Thursday, while sitting at the Benesch meeting in Chicago, I found myself trying to connect dots between the session topics, speaker anecdotes, and the state of things. Not just where we’re headed, but where we actually stands right now. I’ll share more soon about what I heard in the room (and the people I met), but for now, what struck me most wasn’t just what was said on stage. It’s what wasn’t.

Policy changes, payment models, new incentives, new players— all of it’s seemingly up for discussion. But what’s really shifting? What’s stalled? And what should we be paying closer attention to?

This week, I took a step back to look at the numbers again. Five charts. Each one tells a story: progress, inertia, or missed opportunity. Some trends show real momentum. Others expose how hard change really is— even when we know what needs fixing.

These aren’t just data points, they’re signals. Lines, not dots. Together, they help explain where we are now, what’s working, and what still holds kidney care back.

What’s Inside

1. CKD Awareness Remains Stubbornly Low

Despite better diagnostics, digital tools, and national initiatives, 90% of people with chronic kidney disease still don’t know they have it. Why is this so hard to fix?

Summary

Awareness of chronic kidney disease (CKD) remains one of the most stubborn gaps in U.S. healthcare. In 2013, just 7% of adults with CKD knew they had reduced kidney function.1 More than a decade later, we’re closer to 10.5%, even after the introduction of better screening guidelines, risk stratification tools, and population health initiatives. We’re moving in the right direction, but the reality is stark: 9 out of 10 people with CKD still don’t know they have it.

Part of the challenge is clinical: CKD is largely silent in early stages, and tests that flag it often go unnoticed, unreported, or unexplained. But the bigger issue may be systematic. Screening isn’t routine. Follow-up is inconsistent. Most patients don’t meet a nephrologist until they’re already crashing into dialysis— when it’s too late. Despite clear screening guidelines for high-risk groups, fewer than half of people with diabetes receive both recommended tests (eGFR and uACR). And in patients with hypertension but no diabetes, albuminuria is checked in less than 10%. We’ve made modest progress— but awareness and action still lag behind.2

The barriers are familiar: limited time in primary care, fragmented workflows, and a host of misaligned incentives across the system. In a recent Signals brief, we explored four strategies for closing this gap — from primary care to community screening, employer models, and mobile outreach. The takeaway? There’s no silver bullet. But the best programs meet patients where they are…and follow through.

Question: What’s our best bet when it comes to detecting and stopping kidney disease in its tracks? What will it take for us to get there?

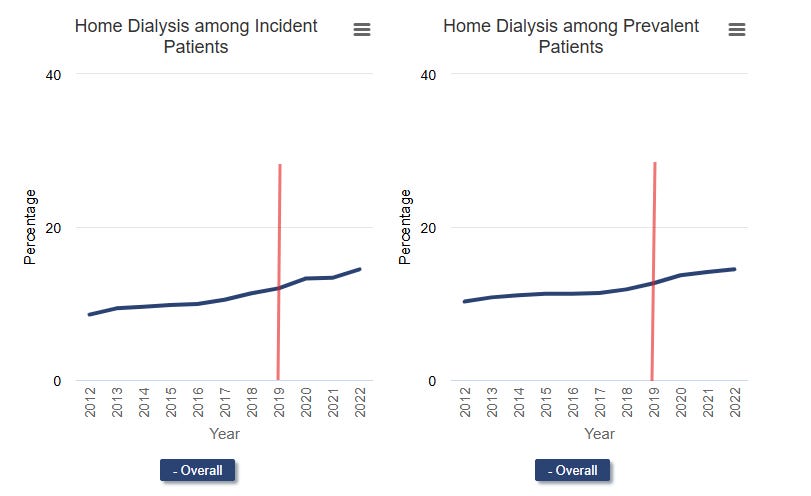

2. Home Dialysis: Modest Gains, Big Ambitions

More patients are starting dialysis at home today than a decade ago— but not nearly at the scale envisioned by federal reform. Why hasn’t this model taken off faster?

Summary

After years of stagnation, home dialysis began to climb in the early 2010s— and got a boost from the 2019 launch of the Advancing American Kidney Health (AAKH) initiative and the ETC model. By 2022, about 1 in 7 new dialysis patients started at home, up from just 1 in 12 a decade earlier. Seventy percent is meaningful progress, but far from the transformation advocates had hoped for. Whether those aims were ever realistic (or meant to be) is another story.3

More recently, the Kidney Care Choices (KCC) Model is showing early signs of momentum in some of the right places. In its second performance year, KCC participants saw a 10% increase in home dialysis use (and a 1% reduction in in-center dialysis to boot), driven largely by a 14% rise in peritoneal dialysis.4 These shifts translated to around 800 additional patients on home therapies in 2023 — and reflect real investments in education, patient engagement, and home-first infrastructure. It's promising, but still early. No matter what happens next, we’ll all be watching closely.

Still, structural barriers persist. Too few clinics offer home training, too few physicians and nurses are experienced with home modalities, and too many patients face psychosocial or logistical hurdles. Disparities remain stark, particularly for patients in overlooked and underserved areas. We broke down these patient-, provider-, and system-level challenges in more detail here.

Newer models are emerging with varying degrees of success. Health systems and startups are investing in better home devices, virtual training, remote monitoring, and stronger patient education. Others are looking at workforce solutions and incentives for facilities that enable more home starts. If we want home dialysis to scale, those levers will need to pull together. That likely means new ways of doing and paying for things, both top-down (policy) and bottom-up (people).

Question: Home dialysis may not be the panacea some say it is, but the delta between patients who could be better off at home and those who actually go home remains vast. What does a best-case scenario for home adoption really look like— and how close can we get?

3. The Transplant Waitlist Is Growing Again

After years of decline, the number of patients on the kidney transplant waitlist is rising. Is this a sign of progress, a warning about widening access gaps, or a bit of both?

Summary

For years, the kidney transplant waitlist was shrinking. But something’s changed. Since early 2024, the waitlist has grown steadily: it’s the first sustained increase in years. In 2022, over 45,000 new candidates were added, the highest number in a decade. In 2023, that number held strong at 44,560, and early 2024 data suggest a continued rise. The reversal may reflect a return to pre-COVID listing activity, but also evolving incentives, like the $15,000 transplant bonus in the Kidney Care Choices (KCC) model. That bonus came up a few times at last week’s Benesch Law meeting as a real driver of new referrals (among clinicians and VBC entities). We recently learned that bonus is going away next year. Those incentives are shifting to newer models. This week, the transplant-focused IOTA model kicks off for 103 participating transplant hospitals.

Increased waitlisting is, in many ways, a sign of progress — especially given historical disparities in access. But it also widens the gap between demand and supply. In 2024, over 27,000 kidney transplants were performed— an incredible feat, but far short of the number of new additions. Today, just 12% of the ESKD population is on the transplant list, down from nearly 18% in 2013. Without more organs, especially deceased-donor kidneys, the current 3 to 10-year wait times could stretch even further.

Nearly 1 in 4 recovered kidneys still go unused, often due to logistical challenges or quality concerns. Reducing that nonuse is one of the biggest levers we have and a key focus of the new IOTA model. So is expanding living donation— though that remains a slower climb, limited by persistent financial and social barriers (continue reading to learn more on this front). The waitlist is growing again. The question is whether the system will grow with it.

Question: Can the U.S. transplant system keep pace with rising demand — or will more patients simply wait longer, with fewer chances to receive an organ in time?

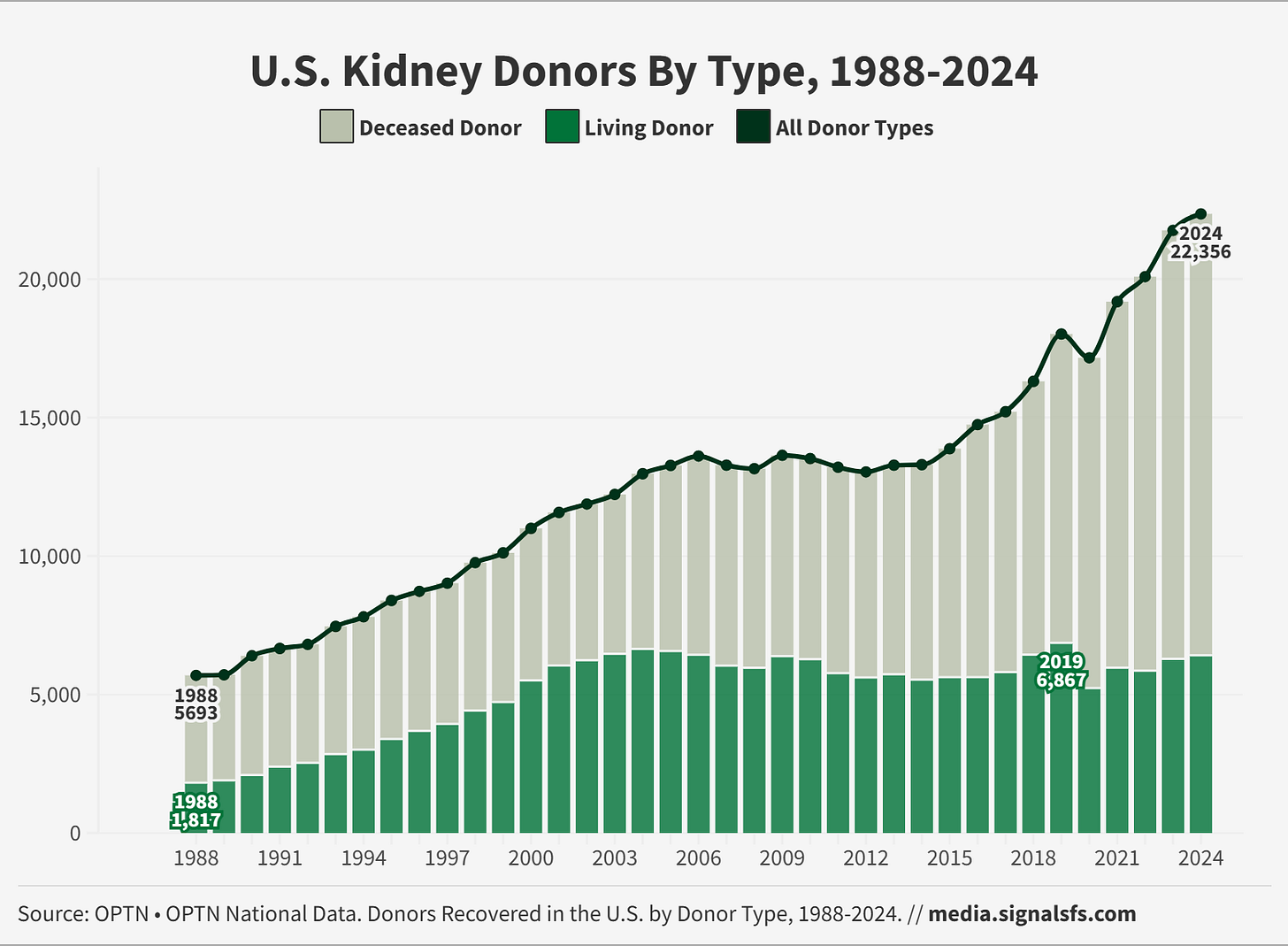

4. Living Kidney Donation Has Plateaued for Two Decades

Despite reforms and rising transplant demand, living donation hasn’t grown much in twenty years. Why is that, and what can be done to address it?

Summary

Living kidney donation has hovered in a narrow range for more than two decades — never falling apart, but never truly growing. Even with rising transplant demand and new policies aimed at removing financial and logistical barriers, the living donor total has never surpassed 6,900 in a single year. The sharp drop during COVID masked a deeper trend: living donation peaked in 2019 and had already stagnated before the pandemic hit.5

What’s holding us back? The risks and burdens on donors are still real — lost wages, insurance uncertainty, travel, long-term medical support, caregiving logistics — and systemic support is inconsistent. CMS has made incremental improvements, and advocacy organizations are working hard to educate and support donors. But progress is slow. For living donation to truly scale, we may need more than tweaks and flyers. Some are calling for bold ideas like direct economic incentives for donors. We may in fact need a structural reimagining of how we find, support, and value donors in this evolving system of ours.6

Question: What do you think it will take to break through the 7,000 LDKT ceiling— and who will need to be involved and engaged to do so?

5. Medicare Advantage Is Now Dominant in ESRD

It took decades to include kidney failure patients in Medicare Advantage. Three years later, MA is now the dominant payer— but questions remain about what that shift really means for kidney care as a whole.

Summary

For decades, patients with kidney failure were effectively locked out of Medicare Advantage (MA). That changed in 2021, when the 21st Century Cures Act opened MA enrollment to all Medicare-eligible individuals with ESRD. The response was swift and even surpassed CMS projections. MA enrollment grew from 25% of Medicare in 2010 to more than half of new dialysis enrollments by 2024, reshaping the payer landscape.7 For many patients, especially those with low incomes or dual eligibility, MA plans offer lower premiums, out-of-pocket caps, and extra benefits, making the choice appealing.8

But the shift hasn’t been without consequences. Concerns are growing about narrow dialysis networks, plan switching, and opaque transplant access.9 Meanwhile, large dialysis organizations have leveraged their market power to negotiate MA reimbursement rates up to 27% higher than fee-for-service Medicare.10 Consolidation and all-or-nothing contracting have changed the financial equation for both plans and providers. Yet MA is no longer the alternative — it’s the new center of gravity. The question now is what kind of kidney care it’s actually incentivizing.

As Dr. Lin notes in his recent JAMA piece, it’s tempting to flatten this into a simple story about market share and margin— but the reality is more complex.11 MA’s rise has brought real financial protections for patients, and the system may still be adapting to serve this newly included population. But with MA now holding the majority, the bigger question is whether this shift will ultimately improve outcomes — or merely redistribute power. Keep this in mind: when the KCC model launched, traditional Medicare was still the dominant payer for people with kidney failure (see Trend 2). That’s no longer the case. This trend will shape what happens next in more ways than one.

Question: Now that Medicare Advantage dominates the ESRD market, what kind of kidney care is it really incentivizing — and for whom?

Closing thoughts

These five trends don’t capture everything, but they do reflect some of the biggest shifts — and tensions — shaping kidney health today. Behind each chart is a story about incentives, infrastructure, equity, and urgency. Some trends are slowly bending in the right direction. Others remain frustratingly flat. And some may be changing faster than we’re ready for.

Of course, there are many more signals worth watching — even if they didn’t make our Top Five this time around. Here are just a few: pediatric kidney disease, donation rates, kidney failure rates, patient awareness and testing, catheter rates, dialysis mortality, AKI follow-ups, rural access gaps, Medigap limitations, nephrology workforce pipeline, CKDnt prevalence, and the growing use of skin grafts.

What else is on your radar? Let us know what you’re seeing, what you’re watching, and what you’re hopeful for. If you learned something new today, consider sharing this post with 1 or 2 people who might find it useful. As always, thanks for being here with us every Sunday, and for all you do to make a difference each day.

— Tim

Work with Signals Group

Our team is expanding across media and advisory to support our kidney innovation partners. Whether you’re looking for new talent, visibility, or expertise to reach your next milestones, we’d love to hear from you.

Share — Tell us what unmet needs you’d like to see solved

Sponsor — Share your work with 15,000 kidney professionals

Subscribe — Support independent kidney news and research

Grow — Partner with us for hands-on advisory and custom research

Lentine KL, Lam NN, Segev DL. Risks of Living Kidney Donation: Current State of Knowledge on Outcomes Important to Donors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019 Apr 5;14(4):597-608. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11220918. Epub 2019 Mar 11. PMID: 30858158; PMCID: PMC6450354.

Nguyen KH, Oh EG, Meyers DJ, Rivera-Hernandez M, Kim D, Mehrotra R, Trivedi AN. Medicare Advantage Enrollment Following the 21st Century Cures Act in Adults With End-Stage Renal Disease. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Sep 3;7(9):e2432772. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.32772. PMID: 39264629; PMCID: PMC11393715.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare payment policy. March 2024. Accessed June 29, 2025. https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Mar24_MedPAC_Report_To_Congress_SEC-3.pdf

Oh EG, Meyers DJ, Nguyen KH, Trivedi AN. Narrow Dialysis Networks In Medicare Advantage: Exposure By Race, Ethnicity, And Dual Eligibility. Health Aff (Millwood). 2023 Feb;42(2):252-260. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.01044. PMID: 36745840; PMCID: PMC10837791.

Lin E. Is Medicare Advantage Advertising Helping or Hurting Patients Receiving Dialysis? JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(6):e2516364. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.16364

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IXc-!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9f7142a0-6602-495d-ab65-0e4c98cc67d4_450x450.png)

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lBsj!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_48,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0e0f61bc-e3f5-4f03-9c6e-5ca5da1fa095_1848x352.png)