Place your bets: kidney health in 2026

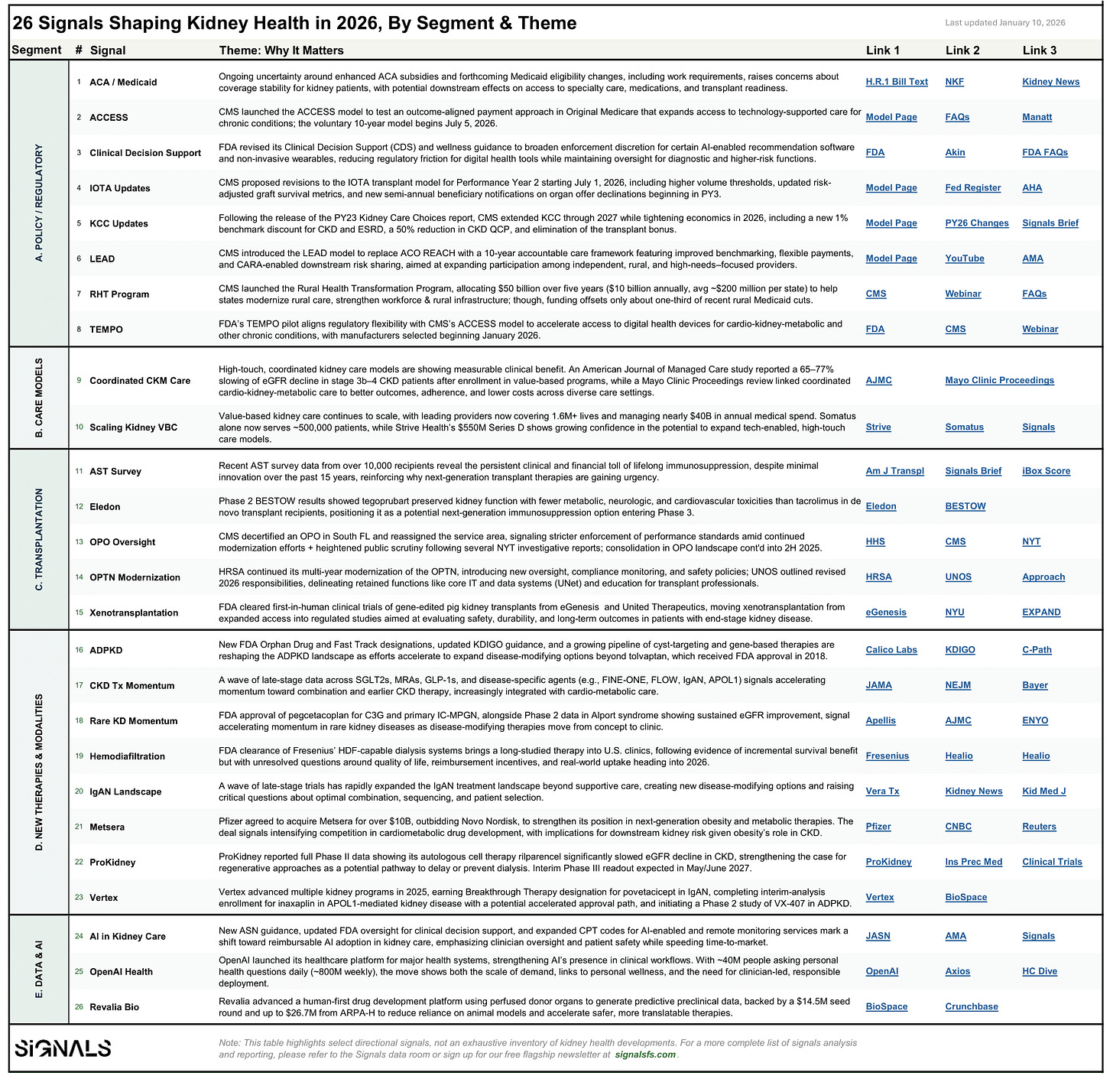

Mapping 26 signals across policy, care models, transplant, therapeutics, data & AI

Each year, I try to step back from the onslaught of headlines and ask a simpler question: what actually changed? Not what was announced or debated, but what truly shifted the underlying terrain.

In past years, I’ve used the image of a stream: headlines as stones, with policy and capital shaping how the water flows around them. This year, that metaphor no longer feels sufficient. What’s changing in kidney health isn’t just the placement of stones downstream; it’s the infrastructure being built far upstream. The systems, incentives, and platforms taking shape now will determine where care can flow, who it reaches, and how durable that progress will be over the next decade.

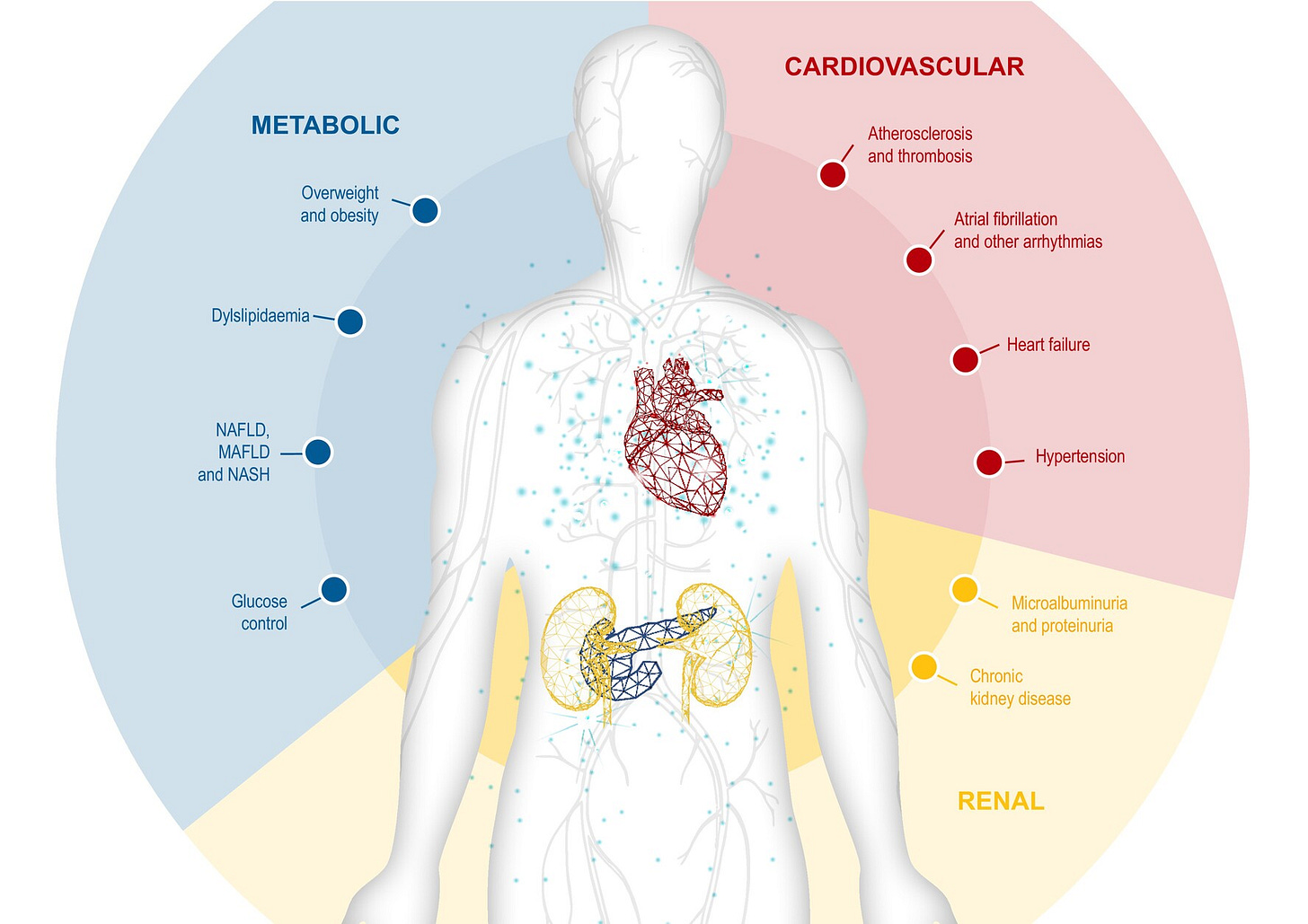

Across cardio-kidney-metabolic (CKM) health, we’re seeing foundational work take hold: new policy frameworks, sustained capital allocation, AI-native data architecture, and care models moving from pilot to scale. These shifts are slower and harder to spot than incremental wins, but in my view they will be far more consequential. They resemble large-scale public works like dams, roads, bridges — projects that quietly reshape what’s possible long after the work is done.

Two years ago, I identified 16 such signals. Last year, it was 25. This year, the list grew again to 26—not because more things are happening, but because more of them are sticking. (“26 in 2026” also has a nice ring to it.) New payment models are coming into focus. Value-based kidney care is maturing. Transplant oversight is tightening. A therapeutic “renaissance” is entering full swing. And data infrastructure is no longer separable from care delivery itself.

Rather than walk through each signal one by one, this piece focuses on the themes that emerge when you view them together. The table below is the reference point. The sections that follow are the lens.

A. Policy & Regulation Take The Driver’s Seat

Kidney care has long been a testing ground for innovative payment and service delivery models, but 2026 marks a shift from experimentation to durability. CMS is no longer asking whether accountable kidney care can work; it is deciding how long these models should run, who they are built for, and how much risk participants must carry. The extension of Kidney Care Choices (KCC) through 2027, the launch of LEAD as a 10-year successor to ACO REACH, and the introduction of ACCESS together signal a strong commitment to tech-enabled, value-based kidney care. In fact, cardio-kidney-metabolic health is a core pillar these new models aim to address.

What stands out this year is not just continuity, but tightening. KCC’s updated economics introduce benchmark discounts, reduce CKD quality payments, and eliminate the transplant bonus. LEAD offers improved benchmarking and flexibility, but over a longer time horizon that favors organizations built for scale and downside risk. ACCESS tests outcome-aligned payments in Original Medicare, enabling clinicians to offer innovative technology-supported care that emphasizes outcomes over activities. Participation remains voluntary, but the economics are increasingly clarifying who can realistically stay in the game. Updated guidance on clinical decision support and digital health devices aim to give providers and vendors clearer operating boundaries as these models mature.

At the same time, policy uncertainty remains. The fate of enhanced ACA premium subsidies, currently in the Senate, could materially affect coverage continuity for people with kidney disease. Cuts or expiration would disproportionately impact low-income and rural patients already facing access barriers. In parallel, CMS has begun awarding the first payments under its Rural Health Transformation Program, marking a concrete step toward testing whether targeted capital and flexibility can support care delivery in underserved regions across America.

Why this matters: Clearer policy signals and longer timelines give providers and innovators a shared direction for building durable kidney care models, echoing the intent of AAKH without the early ambiguity. But that clarity comes alongside real headwinds—tighter economics, potential coverage cuts, and constrained public spending—raising the bar for what can scale and endure.

B. Care Pathways Converge

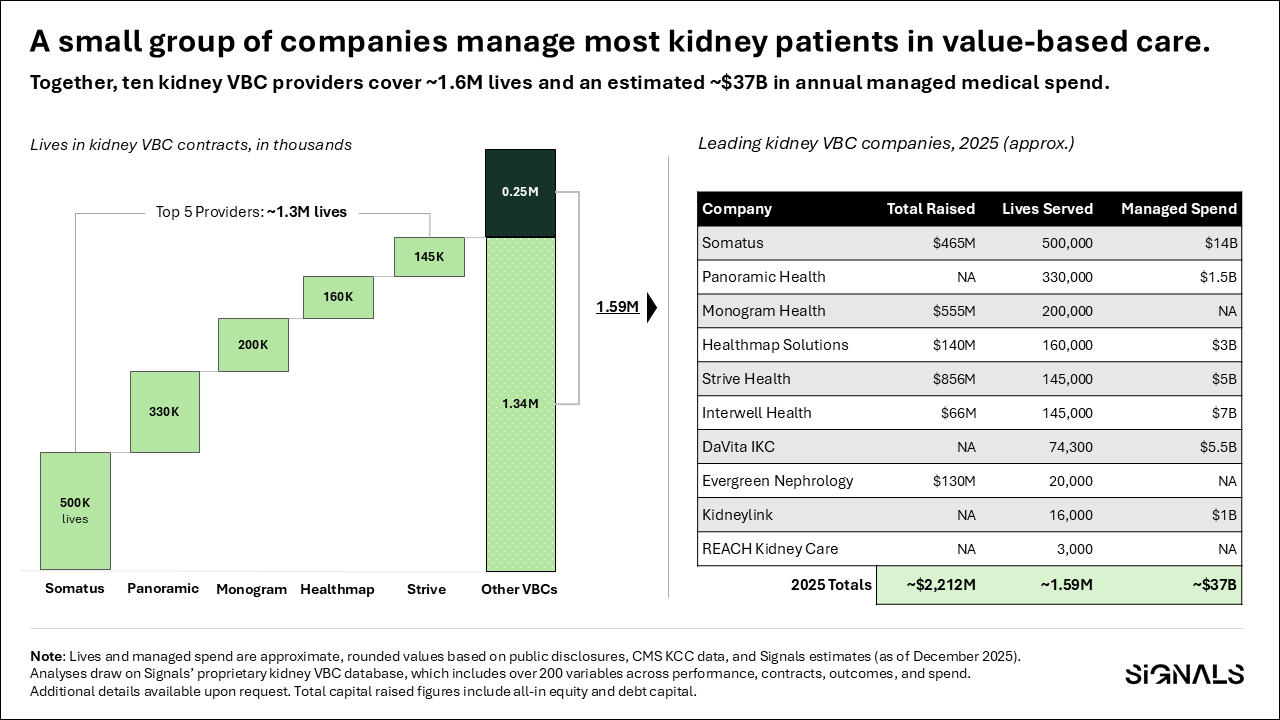

The question of whether value-based kidney care can improve outcomes is largely settled. Evidence continues to accumulate showing slowed disease progression, better coordination, and improved patient experience across CKD populations. The more telling signals in 2026 are about scale.

Leading kidney-focused VBC organizations now cover millions of lives, manage tens of billions in medical spend, and attract billions in late-stage capital to expand partnerships, technology, and clinical reach. Importantly, these models increasingly sit at the intersection of kidney, cardiovascular, and metabolic disease—reflecting how patients actually present, rather than how care has historically been organized.

Why this matters: Integrated CKM care is the connective tissue between payment reform and everything that follows. New therapies, technology, and R&D only work if systems and workflows are organized to deploy them effectively. As kidney patients increasingly present with overlapping cardiac and metabolic diseases, coordinated models move from “nice to have” to essential system infrastructure.

C. Transplant Tightens

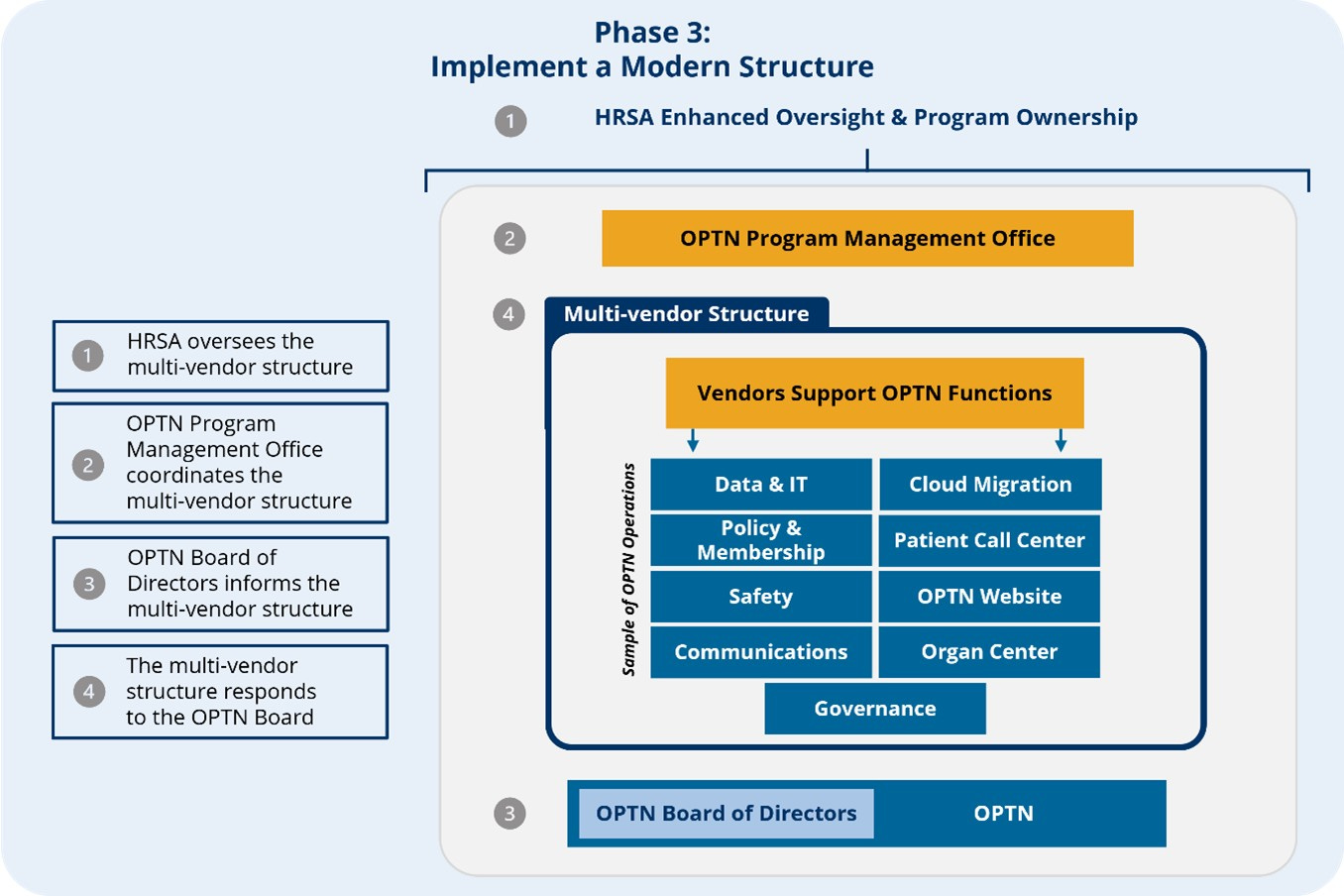

Transplant remains the gold standard treatment for kidney failure, but 2026 makes clear that access and outcomes depend as much on trust and governance as on innovation and discovery. Federal modernization of the OPTN, an unprecedented closing of an underperforming OPOs, and continued consolidation across the procurement landscape signal a system in transition. This also comes at a time when deceased donor volume has meaningfully decreased for the first time in at least a decade, much of which can be explained by decreases in drug-related deaths.

At the same time, transplantation itself is re-entering an era of experimentation. Gene-edited pig kidneys from companies like eGenesis and United Therapeutics have now supported human life for months, backed by FDA-cleared INDs and early clinical trials. While rejection ultimately ended some of these transplants, their durability represents a step change and underscores a parallel truth surfaced this year by AST survey data: lifelong immunosuppression remains a major clinical and financial burden, with limited innovation over the past decade. Whether for human or xenogeneic organs, progress in transplantation is increasingly constrained not by surgery, but by better understanding and regulating the human immune response.

Why this matters: The transplant field is evolving at both the system and biological levels. Oversight is tightening to restore trust, while advances in organ engineering and immunology are reopening questions about who can be transplanted, with what organs, and under what long-term tradeoffs. Beneath both runs a familiar policy thread: transplantation now has its own payment model experiment in IOTA, with public comments due by February 9, 2026—an important reminder that scientific breakthroughs alone are not enough to bring new solutions to patients.

D. New Therapeutics & Modalities

For decades, progress in kidney therapeutics was slow and episodic, with few options that meaningfully altered disease course. That pattern is now breaking. Recent approvals and late-stage data across rare complement-driven diseases, genetic kidney disorders, and cardio-kidney-metabolic conditions point to a broader and more durable pipeline taking shape. Large-scale evidence reinforcing the kidney-protective effects of SGLT2 inhibitors (here and here) further signals a shift from isolated advances toward therapies that can be deployed at population scale.

This momentum extends beyond drugs alone. Advances in dialysis modalities, such as high-volume hemodiafiltration (HDF) enabled by next-generation systems, reflect renewed attention to improving outcomes within existing care settings, not just replacing them. These approaches are not novel, but their emergence in the U.S. signals shifting clinical and commercial priorities that may lead to meaningful benefits for patients needing dialysis and those awaiting transplant.

Why this matters: As disease-modifying therapies become foundational rather than exceptional, integrated care models are increasingly necessary to deploy them effectively. The value of these advances depends less on individual breakthroughs and more on systems that can identify patients early, coordinate care, and sustain benefits over time. As with much of kidney care today, the limiting factor remains early detection and screening.

E. Data Infrastructure & AI

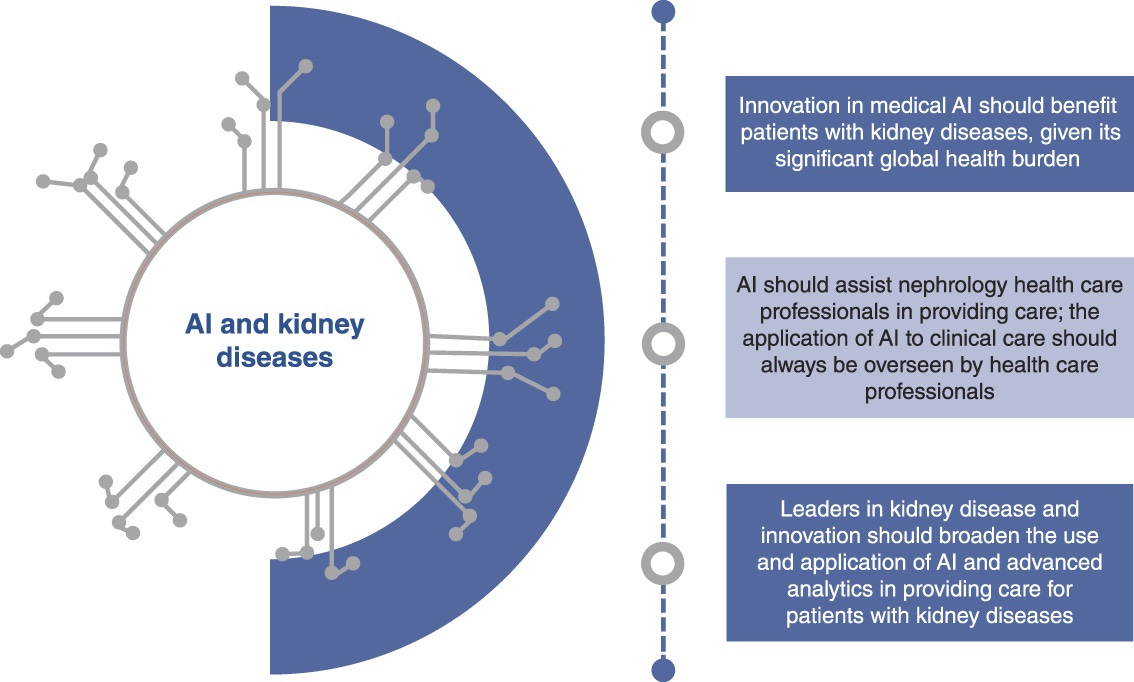

AI is not new to kidney care, but 2026 marks an inflection point in how it is adopted and governed. Professional guidance on responsible AI use, clearer FDA boundaries around clinical decision support, expanded CPT codes for AI-enabled and digital health services, and opportunities for enhanced remote and non-invasive monitoring together reduce long-standing friction around payer adoption. (Counter-examples include “downcoding” and the WISeR model.) The result is not a green light for automation, but a clearer set of rules for how AI can be embedded into clinical workflows with physicians firmly in the loop.

At the same time, demand is accelerating from the opposite direction. Consumer-facing platforms like OpenAI are operating at unprecedented scale, with forty million people asking health-related questions daily (and ~800 million on a weekly basis). That pressure is beginning to intersect with clinical care, especially at the seems where access challenges persist. Upstream, companies like Revalia point to where this is headed next: human-first data that has the potential to reshape how therapies are developed, validated, and translated, years before they ever reach patients.

Why this matters: kidney care is laying guardrails before accelerating. With clearer reimbursement, oversight, and infrastructure in place, the field is signaling a preference for clinically embedded, accountable AI. From what we’ve seen and heard across these other areas, I believe trust, integration, and equity will ultimately determine impact.

Closing thoughts

Taken together, these 26 signals point to something more structural than a typical year of progress. Kidney care is entering a phase where the hard work is less about discovering what might work and more about building the systems required to make those advances durable, scalable, and equitable. Payment models are lengthening their time horizons. Care delivery is integrating across chronic conditions. Transplant oversight is tightening as science pushes boundaries. Therapeutics are moving upstream. Data and AI are being constrained before they are accelerated.

As most of you know, this is hard work. It is slow, expensive, and messy. But once built, it has the potential to quietly determine what flows, who benefits, and how resilient these systems become under strain. The challenges ahead are not a lack of innovation. It is whether we can align policy, capital, care models, and trust well enough to ensure these foundations actually hold. The signals are there. What matters next is the follow through.

I’d love to hear from you. What signals do you see shaping kidney and cardiometabolic health in 2026, and where do you think builders, clinicians, and policymakers should focus next?

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IXc-!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9f7142a0-6602-495d-ab65-0e4c98cc67d4_450x450.png)

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lBsj!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_48,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0e0f61bc-e3f5-4f03-9c6e-5ca5da1fa095_1848x352.png)

I’m ready to see more integrative health in kidney and transplant care. I’ve worked at a VBC company and still felt there was a LARGE gap in services and support, especially for the younger population. A lot of these companies are overworked and focused on scaling their outreach and engagement numbers. Their idea of success comes from how many people they have actively enrolled in their programs and less about the quality of care being provided that their medical teams aren’t providing already. I think the missing key piece is the care team outside of the medical team. The mental and emotional support. The practical support in day to day life.