Most rare disease patients wait years for a diagnosis—if they ever get one at all. Bryce Powerman was one of the lucky ones. Diagnosed with DOCK8, an ultra-rare immunodeficiency, he was referred to the NIH, joined a first-in-human trial, and received a life-changing bone marrow transplant. That experience, he says, shaped everything that came after.

Today, Bryce works at Natera, where he helps biopharma partners accelerate drug development using genetics, real-world data, and patient matching. Drawing on both his personal experience and professional focus, Bryce is helping push the boundaries of personalized care—especially in kidney disease. In this interview, we discuss:

Bryce’s ultra-rare diagnosis and bone marrow transplant at NIH

The diagnostic and therapeutic odyssey—what it means and why it matters

How Natera helps match kidney patients with clinical trials

Why genetics is key to building the kidney disease flywheel

What patient advocates can do to help drive drug development

How Bryce’s personal journey fuels his work in precision medicine today

Those who know me and my background know that I love hearing about people who turn their own health journeys into personal missions to improve healthcare. That’s why I was grateful for the chance to connect with Bryce, hear his story, and learn how he’s turning that experience into a driving force for good in the kidney community.

Let’s start with your story. How did your journey begin?

Bryce: I’m actually an ultra-rare disease patient. I was born with Dedicator of Cytokinesis 8 deficiency—DOCK8 for short. It’s a primary immunodeficiency that left me with about one-seventh the white blood cells of a typical person. When I was diagnosed in the late 2000s, the prognosis was grim. Life expectancy was about 30, and there weren’t many other cases to compare to.

I had a rough childhood—constant infections, lung issues, sinus problems, and more. Eventually, most DOCK8 patients develop cancer, which is often the fatal complication. But I got incredibly lucky. When I was seven and in the hospital for what they thought was Ewing sarcoma, a visiting doctor spotted something unusual in my chart and recommended NIH.

My parents pushed hard, got me enrolled in a broad study for patients with primary immunodeficiencies, and over time, NIH isolated DOCK8 as a cohort. That led to a first-in-human clinical trial using bone marrow transplant as a potential cure. I had one matching donor—a 50-year-old man in Germany—and it worked. That was over 11 years ago. I’m healthy now, off all meds, married, and living in San Francisco. (And older than 30!)

Have things changed since your own diagnostic journey?

Bryce: A lot has changed—and we still have a long way to go. It took me 14 years to get a genetic diagnosis. Today, with tools like rapid whole genome sequencing, we’re diagnosing some patients within 14 days of birth.

That’s the power of early testing. Not only does it give you clarity sooner, it also helps connect patients with advocacy groups, which is huge. Those communities are vital. They provide support, they organize trials, and they often drive drug development by making it easier for biopharma to find and learn from patients.

What does that support look like in practice?

Bryce: It depends on the stage.

Early on, we use our data—over 6,000 patients tested each month—to help researchers understand the disease and patient landscape. We can answer questions like: How many patients have a certain variant? Where are they located? How are they progressing?

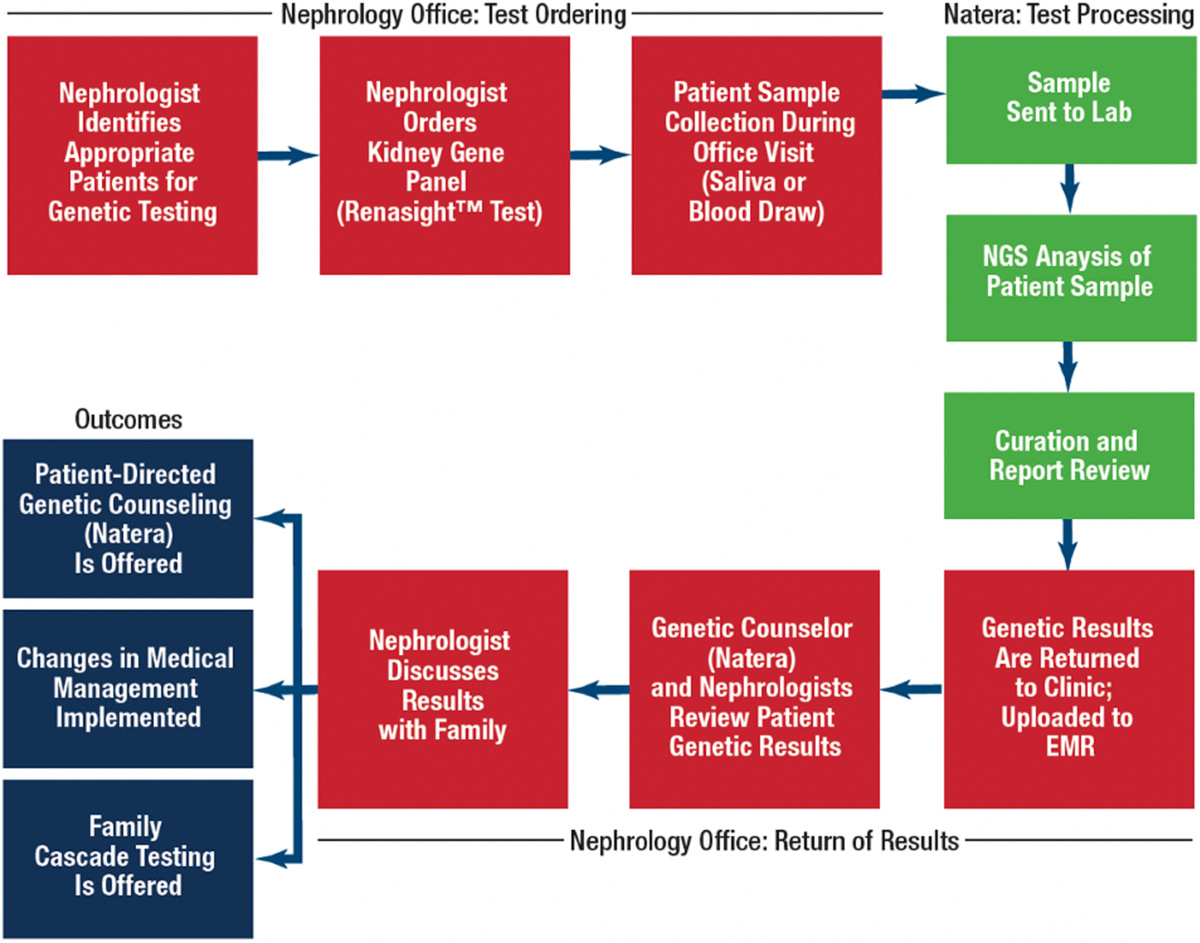

Then during the clinical trial phase, we run a patient-matching service. If a patient recently took our Renasight test and might qualify for a trial, we reach out to the clinician and then directly to the patient to provide education. We’re not in the business of guiding care—we just want to make sure patients know their options.

Finally, post-approval, we help biopharma companies educate nephrologists. That’s a big one in kidney care. It’s a space that hasn’t had a lot of therapeutic activity, so it takes a lot of outreach and trust-building.

How did kidney disease become a focus for you and Natera?

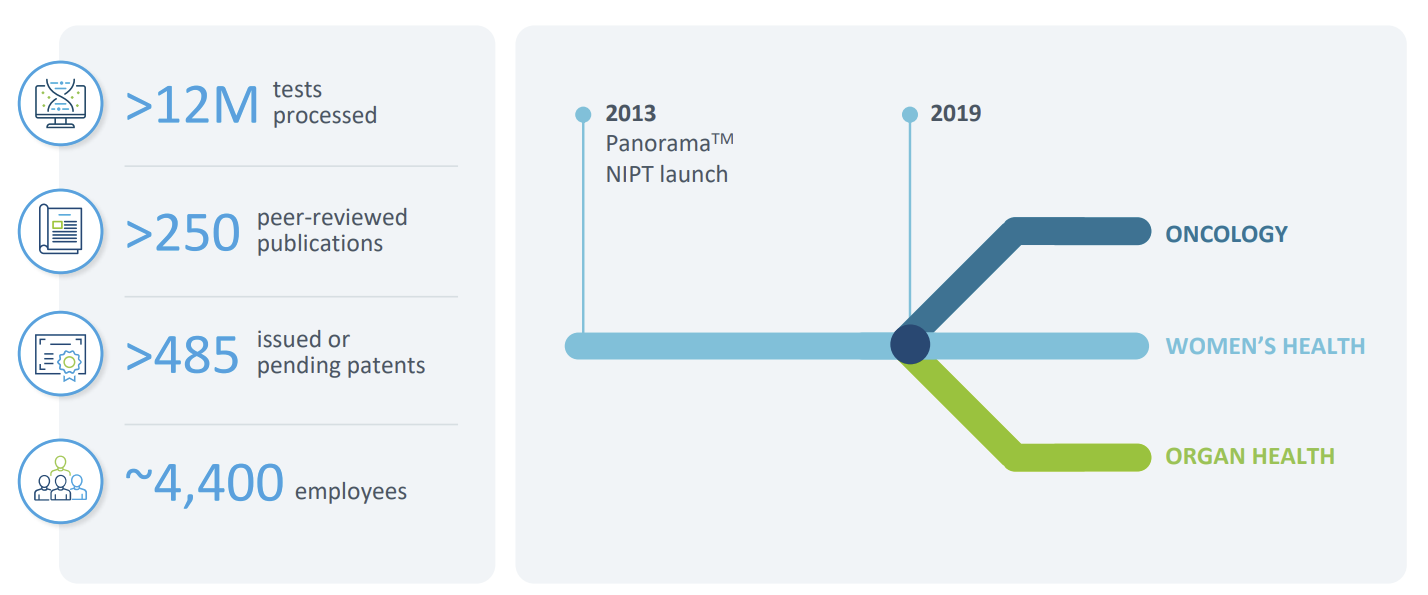

Bryce: It started with our work in transplant rejection testing. Natera launched Prospera, a cell-free DNA test that can detect organ rejection with a simple blood draw. That was 2019.

We then saw a gap in the chronic kidney disease space—genetics wasn’t being used widely. So in 2020, we launched the Renasight gene panel, which includes about 400 genes known to be associated with CKD. It's now been adopted by over two-thirds of nephrologists in the U.S.

There’s still work to do, but we’ve made real progress in showing how genetics can inform diagnosis, trial matching, and even drug targeting in kidney care.

What’s the total opportunity here—how many patients are we talking about?

Bryce: 6,000 patients per month are tested through Renasight, but that’s just scratching the surface. To date, we’ve tested more than 150,000 people. Still, there are an estimated 37 million American adults with kidney disease. The genetic driver rate in CKD is estimated to be as high as 1 in 5. That means there are likely hundreds of thousands of people out there who could benefit from this type of testing, particularly those with early-stage disease or unexplained CKD.

We’re working to get further upstream, but it takes education and system change. Not every nephrologist is used to ordering genetic tests, so we’re building that awareness steadily.

You mentioned the Renasight database. What is it, exactly?

Bryce: It’s the ecosystem we’ve built around Renasight—combining genetic and clinical data to provide deep insights into patient populations. That helps us support drug development in several ways: identifying trial sites, stratifying patients, and understanding response patterns.

It also powers our trial matching service. If we identify a patient with a relevant genetic variant, and they’ve consented, we can proactively reach out with trial options. That’s rare—and incredibly valuable.

What’s your advice to patients or advocates who want to get involved?

Bryce: Find your people. Advocacy groups are game-changers—for information, for emotional support, and for advancing research. Once you have a diagnosis, you’re not alone. There’s likely a group already working hard on behalf of patients like you.

Beyond that, education is everything. The more patients know, the better equipped they are to make decisions, ask questions, and participate in opportunities like trials.

And what about the industry side—what do you wish stakeholders better understood?

Bryce: For biopharma: diagnostic companies like Natera can be key allies in drug development. We bring data, patient access, and real-world insights that can speed up trials and improve targeting.

For clinicians: I’m obviously a big advocate for genetic testing. The more we test, the more patients we diagnose—and the more opportunities there are for those patients. It builds a flywheel. More testing means more diagnosed patients, which draws in more research and therapeutic development, which then encourages more testing. That’s how we build momentum in kidney care.

My thanks to Bryce for joining us and sharing his story. For more on the power of genetic testing in kidney disease, see the 2023 JASN RenaCARE study, where 1 in 5 patients tested positive for a genetic cause of CKD and 1 in 3 had a change in treatment. The ENYO case study shows how Natera’s patient-matching platform accelerated trial enrollment for Alport syndrome by 3x—completing in 5 months versus the 16-month industry average. A 2024 collaboration with the Alport Syndrome Foundation highlighted common COL4 gene variants and the evolving role of precision diagnostics in rare kidney disease. In 2025, a study published in Urolithiasis used Renasight to identify genetic drivers in high-risk kidney stone patients, reinforcing the value of testing in recurrent stone disease. And back in 2022, the Renasight 1000 study revealed that 25% of early patients tested had a genetic finding, with nearly half carrying rare variants not detectable with limited panels.

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IXc-!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9f7142a0-6602-495d-ab65-0e4c98cc67d4_450x450.png)

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lBsj!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_48,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0e0f61bc-e3f5-4f03-9c6e-5ca5da1fa095_1848x352.png)

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!NnOt!,w_144,h_144,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F688fc47b-7202-4a2e-b4f4-fea2b047ab1b_1500x1500.png)