Most people with kidney disease who need a transplant do not learn about the process until far too late in their journeys. But for Jullie Hoggan, a transplant recipient, peer mentor, Transplant Director at patients.app, and co-founder of Square Knot Health, the journey started long before her kidneys failed. From a frightening polycystic kidney disease (PKD) diagnosis at 26 to navigating a maze of delays, paperwork, and missed opportunities, she eventually found her way to a preemptive transplant and built a career helping others avoid the same barriers.

Today she is one of the most compassionate and compelling voices in transplant advocacy. In this conversation, she shares her story, the turning point that changed everything, and how lived experience, peer support, and better technology can reshape the entire patient journey. The seeds for this interview were planted years ago when we first met, and I invited Jullie to share her story after reconnecting at the transplant congress in San Francisco a few months ago.

What’s Inside

Early PKD diagnosis, fear, and finding clarity

The class that revealed how broken the system is

Why every patient needs a “kidney friend”

How Square Knot Health came to life

Fixing delays with better data and tech

The missing support system for living donors

I hope you enjoy this discussion, learn something new, and share Jullie’s perspective with someone who needs it today. Thanks for being here with us.

Q&A with Jullie Hoggan

Let’s start with your story. How did you first learn you had polycystic kidney disease?

JH: I was 26 when I was diagnosed, though the story really started years earlier. I had high blood pressure at 19 and was simply treated—no one asked why someone that young would have it. Years later, when I was hoping to get pregnant, a new doctor finally asked the right question and sent me for an ultrasound. A physician I knew from work came out and said, “Jullie, you have polycystic kidney disease.”1

I had never heard of it. This was 1997 or 1998, when the internet had only enough information to scare you. I remember going to my husband’s office, both of us sitting there searching online, trying to understand what this meant. Back then, you found bits of information about aneurysms, heart problems, and kidney failure—just enough to make you terrified, but nothing that helped you understand what to do next.

Then I went to my first nephrology visit and was essentially told, your kidneys look bad, but they work—come back in 20 years when they fail. That was the entire care plan. No urgency, no roadmap, nothing to help me prepare for the life I was going to have to live.

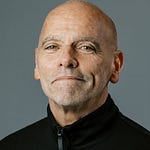

Figure: Cyst formation at the level of the cell, nephron, and kidney.

Was there PKD in your family? Were you thinking about that then?

JH: Interestingly, no. But figuring that out took years. I wanted genetic testing almost immediately because I had a daughter, but in the early 2000s it wasn’t easy. I joined the Tolvaptan trial and then a genetic study in Colorado.2 They took my sample and two years passed without any information. When I finally called, they told me I had PKD1, but they couldn’t find the mutation at first because it was novel.3 They didn’t have it in any database.

Years later, Arkana Labs found it in about five weeks. They also offered to test my daughter, who had grown up thinking she had a 50–50 chance. She doesn’t have my mutation. That changed everything for us. After 19 years of uncertainty, it was like a weight lifted off our whole family.

When did transplant become something you knew you had to prepare for?

JH: When my GFR hit 29. No one told me to do anything then—I just knew. I called the transplant center and asked what needed to happen. They gave me a list of screenings, so I got them done. I also kept an enormous binder—five inches thick—with every scan, lab, clinic note, and clinical trial document I had. No matter where I went, someone was missing a piece of my record.

When my GFR dropped from 21 to 19, I immediately asked my doctor for a transplant referral. They hesitated, but 20 is considered the national threshold for listing, and I knew that. When the transplant center received the referral, they told me it would take two months to mail paperwork and another two or three months to gather and review my records. Meanwhile, I had everything ready to hand them.4

It was clear the urgency I felt as a patient was not matched by the system. And when you’re losing kidney function, every month matters. Those delays can mean the difference between getting a kidney before dialysis or ending up on dialysis for years.

There’s a moment in your story you’ve described as a turning point, the transplant education class. What happened that day?

JH: There were about 50 of us in the room that day. The first question was, “How many of you are already on dialysis?” Every hand went up except mine and a friend’s, and she was planning to start dialysis soon. Out of 50 people, I was the only person who would eventually get a preemptive transplant.

I stopped hearing the class. I just sat there thinking, How is this possible? How am I the only one?

I learned later that my local support group had been running for 14 years—and not a single person in that entire time had ever had a preemptive transplant. Not one. That moment sparked everything. I knew something bigger was wrong. Patients weren’t being guided early enough, clearly enough, or consistently enough. And that realization became the foundation for everything I do now.

You’ve talked about the role of peer support in your journey. How has it helped you?

JH: Peer support fills in all the gaps that clinical visits can’t. In an eight-minute appointment, the emotional side doesn’t get covered—the fear, the logistics, the grief, the uncertainty, the “what ifs.” In peer groups, you can talk about the things you don’t want to burden your family with. You can say, “I’m scared,” or “I don’t know what to expect,” or “I don’t understand what the doctor just told me.”

Peers also translate the system. They’ve lived it. They know how transplant evaluations work, what questions to ask, which barriers are normal, and which ones you should push back on. That kind of guidance is priceless.

And I’ve learned something important: people rarely join a support group when you tell them, “You need support.” But if you say, “You’ve been through a lot—someone else could really use your help,” they show up. They come for others and end up receiving support without realizing it.

For people who may not be familiar, what exactly is a preemptive kidney transplant, and why is it so important?

JH: A preemptive kidney transplant means receiving a kidney before ever starting dialysis. It is the best treatment we have for kidney failure. The best outcomes come from a living donor kidney before dialysis. The next best is a deceased donor kidney before dialysis. Dialysis is our third-best option, and although it is lifesaving, the first year on dialysis is very hard for people.

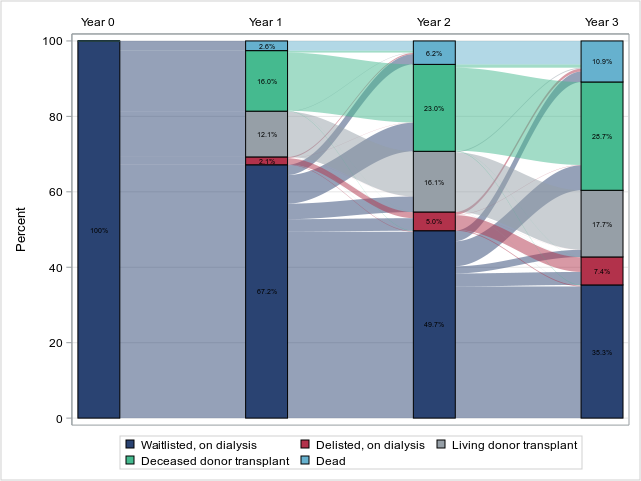

Figure: Outcomes in the 3 years following kidney transplant waitlisting during 2017-2019 among patients receiving dialysis

In the United States, about 97 percent of people who reach kidney failure start on dialysis. Only about 3 percent receive a transplant first. That gap is enormous. And the reason is timing. You can only be listed on the national waitlist when your GFR is 20 or below. If no one tells you that, or if you are referred too late, you miss the chance to build waiting time or find a donor.

The system is not set up to help people early. That’s what drives so much of the work we do now.

How did Square Knot Health actually come together?

JH: After my transplant, I left my ICU job because it was early COVID and I couldn’t risk that exposure. I wanted to work in kidney care but didn’t know where I fit—I’m a speech pathologist, not someone with the typical letters kidney organizations look for.

Then someone I met in a support group said, “You need to talk to my nephrologist at Mass General—you think the same way.” I didn’t believe her, but she kept nudging me. I finally emailed him, thinking nothing would come of it.

Dr. Heher called the next day. And by the end of the conversation, he said, “I think we should work together.”

Something shifted in me immediately. I remember hanging up and thinking, I’m never going back to speech pathology. It felt like everything I’d done in my life, my medical background, my patient experience, my communication skills, had prepared me for this without me knowing it.

His vision was simple but bold:

Hire transplant recipients, donors, and caregivers as navigators and pair them with patients to help them get transplanted sooner. To support not just the medical system, but the patient journey from start to finish.

It was exactly what I wanted to be part of.

Technology plays a big role in your work. What does it do, and how has it helped transplant centers?

JH: The biggest bottleneck we kept running into was medical records. We were getting charts that were hundreds or thousands of pages long—PDFs, faxes, scanned documents, lab reports buried everywhere. Our navigators were spending hours trying to find the handful of things that actually matter for an evaluation. It’s the same problem I ran into firsthand, and that transplant centers are having to do every day.

So we partnered with patients.app to build something that could pull in medical records from across the country, standardize them, and use AI to extract all the key transplant data—over 150 items. And importantly, every extracted item has a direct citation link back to the original page in the chart.

For transplant centers, this can cut months off the referral-to-listing timeline. It also gives them confidence in their waitlist—so when a kidney becomes available, they know exactly which patients are ready. And for patients, it removes a huge amount of fear around “being lost in the system.”

We’ve talked about living donor support being one of the biggest gaps in the current system. What makes it so hard?

JH: Almost every patient says, “I’m not asking anyone to do this.” And I always tell them, “Good—you don’t have to ask. You just have to tell your story.” We help them find language that feels comfortable and authentic.

I’ve spoken to more than 100 potential donors. Many want to learn privately before going to a transplant center. Just knowing someone is even thinking about donation can give a patient extraordinary hope.

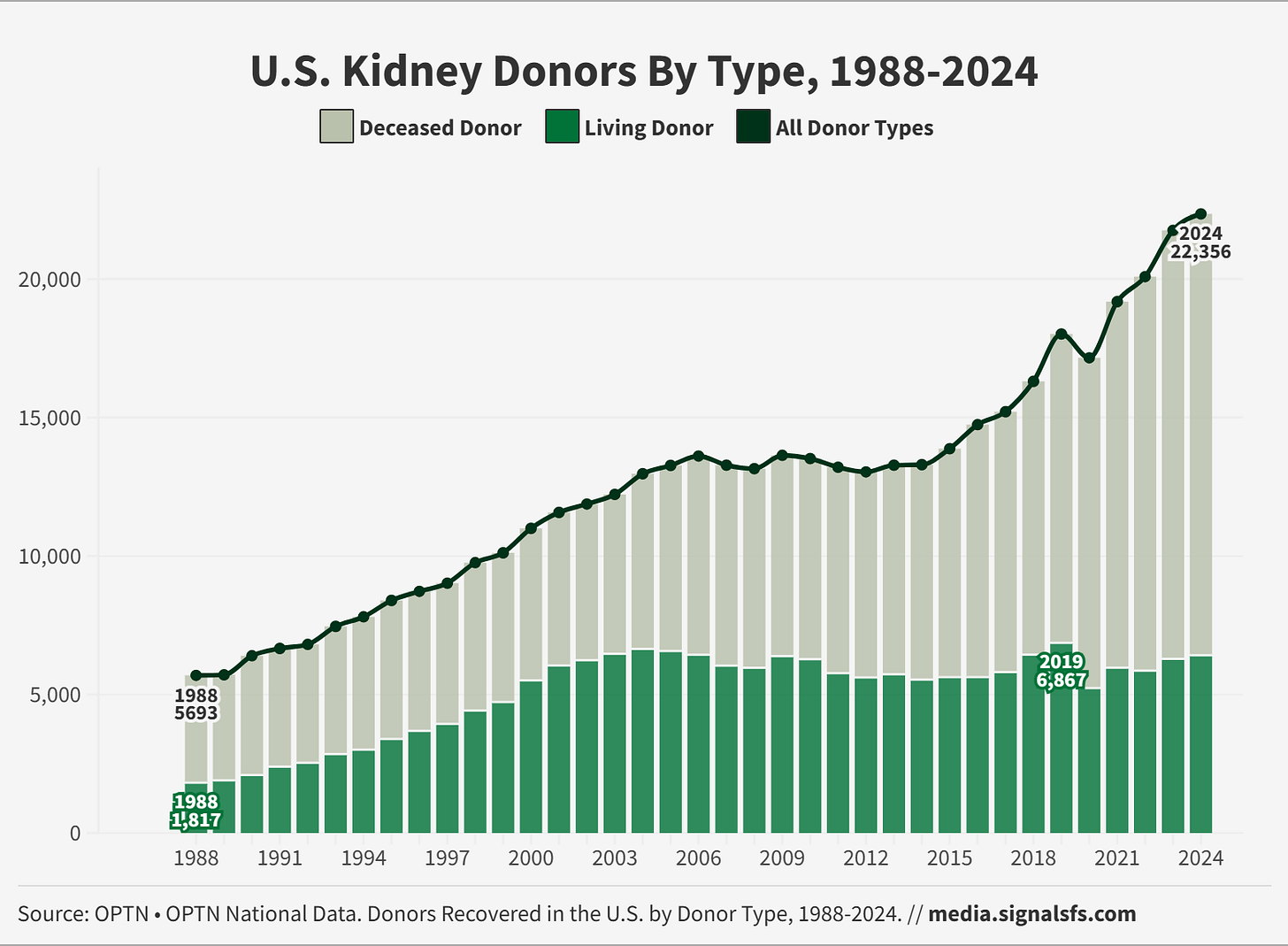

But the larger issue is that we don’t have a national system to support living donor transplant, our best treatment option. It’s astonishing that something so critical relies almost entirely on nonprofits, volunteers, and patient advocates.

Why is it still so hard to fund navigation and advocacy work?

JH: Because the financial savings come later. Avoiding dialysis saves hundreds of thousands of dollars, especially if transplant happens before dialysis. But most health plans budget year by year. If the benefit doesn’t show up in the same fiscal year, it’s considered a loss.

Until incentives change, nonprofits and volunteers will continue carrying the load. It’s not sustainable, but it’s where we are today.

Figure: Living Kidney Donations Have Been Flat For Decades

What gives you optimism right now?

JH: When I go to meetings and conferences, I look around and see an entire ecosystem of people, nephrologists, surgeons, coordinators, social workers, innovators, all trying to make things better. Patients don’t always feel seen, but there are so many people fighting for them.

We just need to better connect the pieces. And we need patients at the table when decisions are made. That’s where the real progress will come from.

What do you want every transplant patient or family to know?

JH: Everyone needs a “kidney friend.” Peer support changes outcomes in ways we don’t yet measure. And mental health should be part of transplant care. Even when things go well, transplant is traumatic—physically and emotionally. I wish counseling had been part of my care from the beginning. I think most patients would benefit from that type of care.

[End of Q&A]

We’d love to hear from you. What questions do you have for Jullie? What stories can you share, and what would you like to learn more about?

Thank yous

My thanks to Jullie for sharing her story with us today. If you’re interested in her work, you can reach out to learn more about Square Knot and patients.app. If you’re interested in these topics, you might also enjoy our recent articles on Life on Immuno-suppression, Five Charts that Explain Kidney Care, or How Intermountain Does Patient Navigation. Dr. Karin Hehenberger’s recent guest post, titled “Too Grateful to Complain?”, discusses why organ transplantation lags behind oncology in innovation and public voice. Finally, other recent transplant patient stories include Kevin Fowler and Michelle Yeboah. Thanks for being here with us.

This issue is made possible by Natera. Natera supports personalized kidney care and drug development through advanced genetic testing and insights. RenasightIQ™ is a robust clinicogenomic database of 170,000+ chronic kidney disease patients enriched with longitudinal clinical and claims data. This powerful platform delivers real-world insights from early investigation to commercialization to accelerate the kidney disease drug development lifecycle.

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) causes fluid-filled cysts in the kidneys, leading to kidney damage and failure. In the United States about 600,000 people have PKD, which is the fourth leading cause of kidney failure. Men and women are equally at risk for the disease. It causes about 5% of all kidney failure. (kidney.org)

“The goal for referral should be that all potential candidates are referred for transplant at a GFR above 20 to avoid the development of comorbidities associated with dialysis and to allow the patient the maximum waiting time available.” (optn.transplant.hrsa.gov)

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!IXc-!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9f7142a0-6602-495d-ab65-0e4c98cc67d4_450x450.png)

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lBsj!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0e0f61bc-e3f5-4f03-9c6e-5ca5da1fa095_1848x352.png)

![Signals From [Space]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!NnOt!,w_152,h_152,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F688fc47b-7202-4a2e-b4f4-fea2b047ab1b_1500x1500.png)